7 different types of traditional Russian dwelling

1. Izba (Russian house)

The history of the Russian izba dates back a long way, and they’re still being built in rural and suburban areas of Russia.

An izba is constructed by putting square frames of logs (a single frame is called a

2. Igloo

The igloo is a traditional

Measuring up to four meters in diameter and two meters in height, igloos are made of ice blocks. Snow is used as an insulator because it traps air while the entrance is lower than the floor, helping carbon dioxide to exit while keeping the warm air. An igloo’s floor can be covered with animal hides and cups containing burning oil heat up the interior. Igloos can be quite comfortable; there’s even an igloo hotel in Russia’s

3. Chum

Chums are made of reindeer hides wrapped around wooden poles, with their upper ends tied together. The fireplace is in the middle with a smoke exit cut in the top. Each chum’s floor is covered with hides. According to the Ural peoples’ beliefs, all family members must take part in the construction of a chum, even toddlers help out a little.

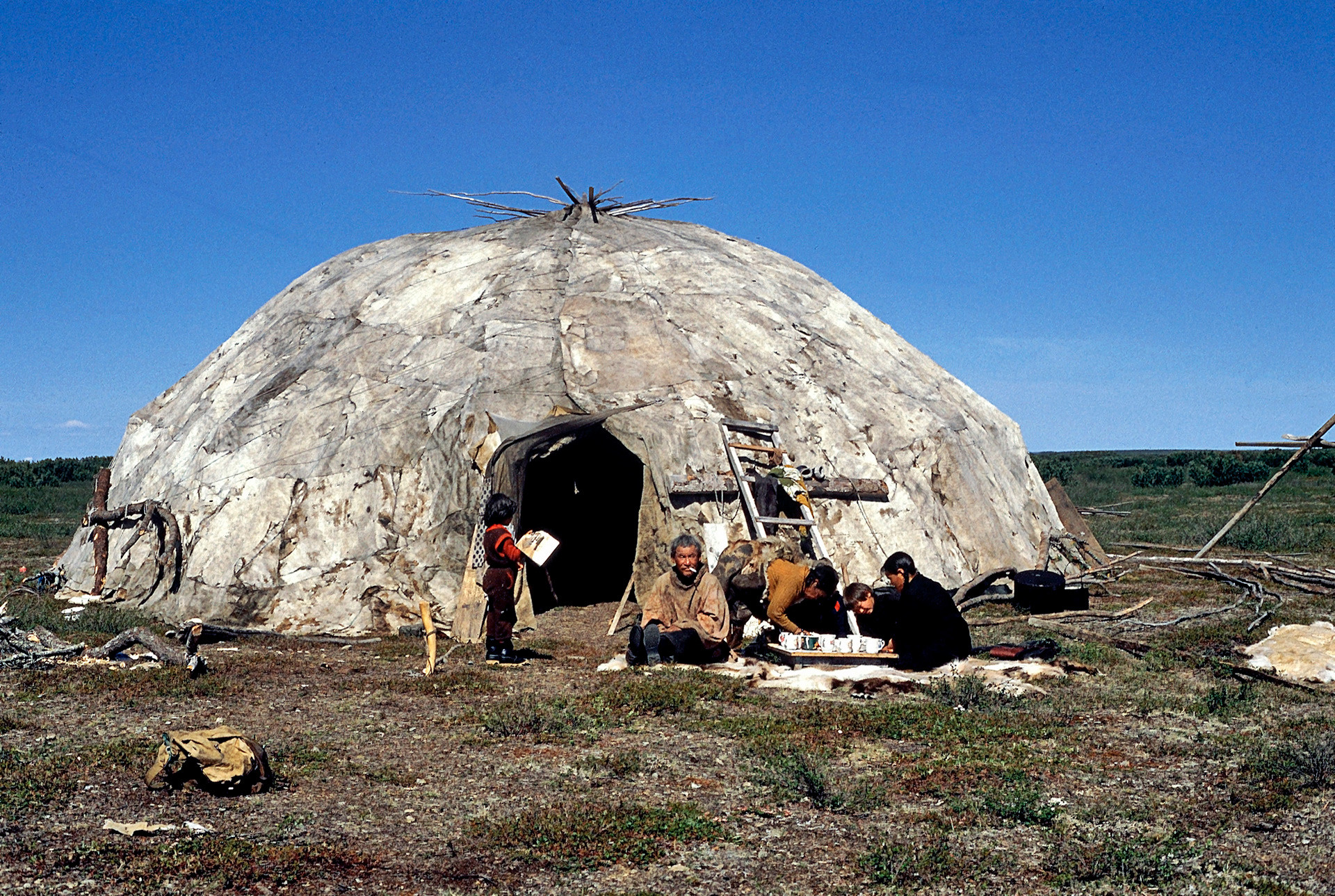

4. Yaranga

These are traditional portable dwellings made by Siberian peoples like the

5. Yurt

Yurts are also portable houses, similar to chums and yarangas, but much larger and complicated. They are mainly used by indigenous people from Siberia and the Baikal Region.

A yurt usually sits low to protect it from the harsh winds of the steppe. Its walls consist of a foldable framework covered with cloth, and poles make up the yurt’s iconic dome - again there’s an opening to let smoke flow out of the top. When it’s hot, the cloth walls are raised to let fresh air in. Inside, it is divided into two halves, for the husband and wife.

6. Ail

An ail (pronounced aah-eel) is wooden house only seen in the Altai Region and is slightly different

7. Saklya

Saklya huts are used by indigenous people from the North Caucasus. They differ from other types of

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox