Why Russians don’t differ much from Americans

Screenshot from 'Rocky 4'

KinopoiskSince the 2016 U.S. presidential election, Russophobia in America has infected the country's political and media establishment, reaching and even surpassing Cold War-era levels.

I had just moved to Russia at about that time, and one day in a bar I sat next to a nice Russian woman who, after finding out I was American, asked, “why do you hate us so much?” I responded by shrugging and

I then thought about it for a while and realized that people who never visit other countries often only have two things to judge them

The U.S. president is a bombastic, overweight businessman. Russia's president is a lean and tough looking former intelligence officer who allows himself to be photographed shirtless. The preposterous manner how media portray these two leaders

Despite our incredibly interconnected world and vast amounts of information on the Internet, these patently false impressions only seem to grow stronger. Therefore, it's no surprise that when Americans think of a Russian they think of someone who is scary, never smiles, drinks vodka and probably is a spy. Likewise, when Russians think of an American, they think of someone who is loud, fat, loves guns and probably is a spy

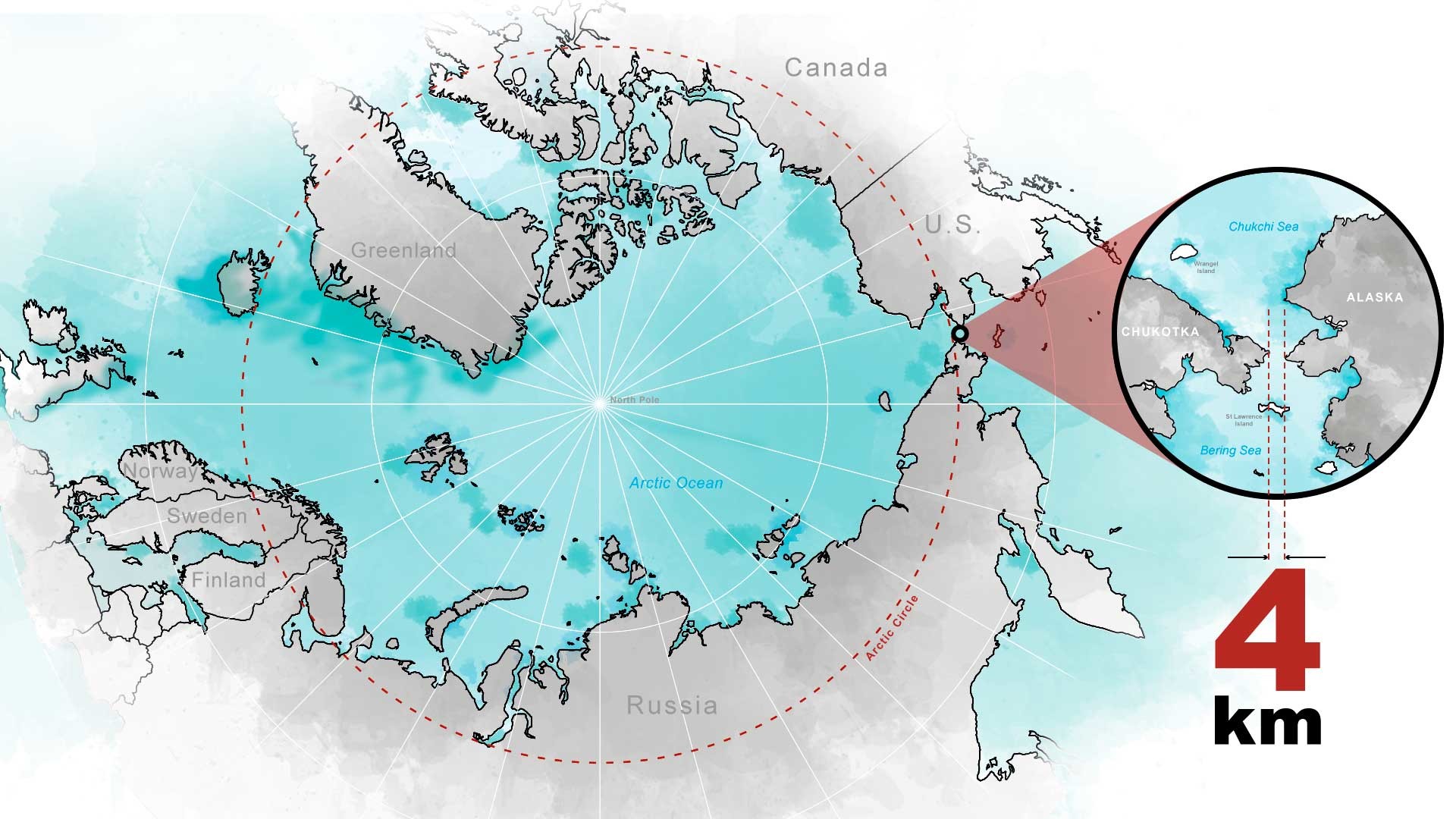

Russia is not as far from America as it may seem

For example, when I see my Russian tutor at the end of each weekend she tells me about spending time with her grandson at the park, and how they went to see a movie, and at some point in the

Russians don’t always know which book they want to read and sometimes they start three or four without finishing even one. They sometimes like ice cream enough to go out in the rain to get it, and they argue whether pineapple is a reasonable topping for pizza. (It isn’t)

Russians aren’t different from Americans because in the

So, if Trump turns a twitter war into an actual war, or some news story reveals that Putin has a robotic Kalashnikov-arm, remember that Russians and Americans are both just people and we’ve all got our own problems to worry about.

Benjamin Davis is an American journalist and author of The King of Fu living in St. Petersburg, Russia where he spent a year working with Russian artist Nikita Klimov on their project: Flash-365. Now, he primarily writes magical-realism flash fiction stories about Russian culture, self-deprecating mishaps, and babushkas while sharing his exploits on his Telegram channel.

Read more by Ben Davis: How Russians changed my life

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox