Meet Tamara Cheremnova: She's spent her whole life in a care home and become a famous author

There are two Russian women on the BBC 100 Women 2018 list: Svetlana Alekseeva, who became a model despite having burn scars all over her body, and "Storyteller of Siberia” Tamara Cheremnova, who lives with cerebral palsy.

At first, staff at the care home where Tamara has in effect spent her whole life laughed at her creative ambitions. She couldn’t even hold a pen herself, so her roommates wrote down her stories and fairy tales from Tamara’s dictation. But when the staff read her manuscripts, they fell in love with the style and plotlines. They were shocked: how could a person with “an intellectual disability” write like this?.

Against all odds

Tamara was born on Dec. 6, 1955 (she recently turned 63). Shortly after birth, she was diagnosed with cerebral palsy. When Tamara was six, her parents put her into a specialized care home. Without properly examining the girl's abilities, the doctors diagnosed her with "intellectual disability." That’s why, when she turned 18, Tamara was sent to a psycho-neurological institution, i.e. a mental asylum.

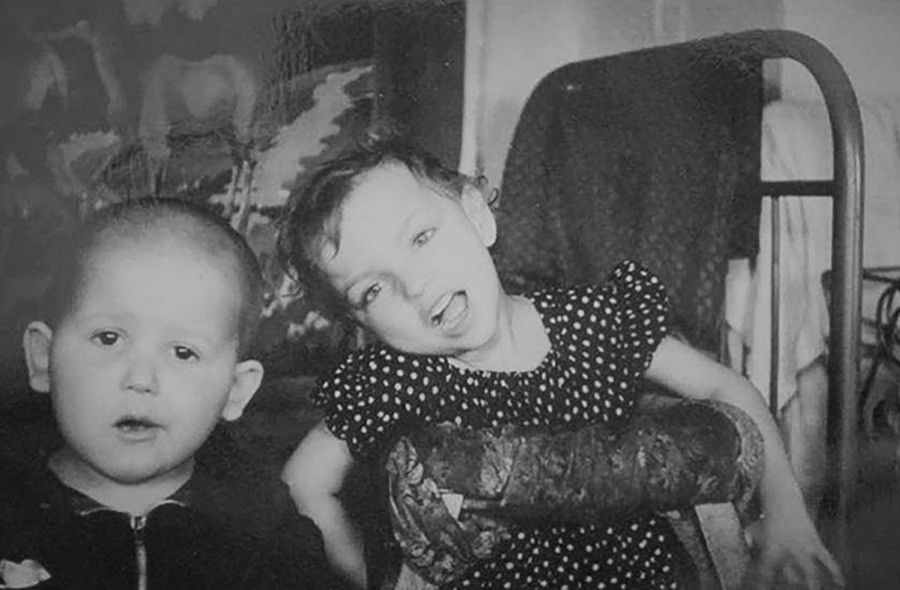

Tamara with her cousine

Personal archiveIn 1963, former school teacher Anna Sutyagina joined the staff of the care home and started teaching the children. She taught them the alphabet and how to read – and read classical literature to them. “It was literature that would later help me to cope, not to give up, not to lose human dignity. Books filled my life with meaning,” Tamara writes. Incidentally, it was through page numbers that she learned to count to 100 and beyond.

Tamara describes some terrible moments from her life in her autobiography Grass, Asphalt Samples. How, as a little girl, she was left in a care home, how the staff sometimes treated her cruelly, how she was only allowed to go to the toilet at specific times, how lonely she felt and even hungry at times.

Her parents visited her from time to time but those visits only upset Tamara more, because her parents did not take her back home. Having grown up, she realized how hard it had been for her parents. In the Soviet Union, the diagnosis of cerebral palsy was tantamount to a prison sentence: people with disabilities were considered second-rate people, who could never live a normal life.

Still, Tamara believes that had her parents put in more effort, had they given her at least some basic massages or simply taken her from the cot and put her on the floor, she could have made some progress when she was small. After all, in the care home, Tamara even learned to sit up on her own.

“All they had to do was to overcome the false shame that their child was not like other children and needed more care and medical attention,” Tamara writes in her autobiographical essay How I Raised Myself.

Then she decided to take her fate into her own hands and wrote a letter to Academician Yevgeny Chazov telling him her life story. And a miracle happened: her medical history was reviewed and the diagnosis ruled erroneous. Then Tamara was transferred from a mental to a general care home. “It is not a sanatorium and not home living, but still better than a madhouse,” Tamara says.

‘Storyteller of Siberia’

In 1990, Tamara's first children's book, From the Life of the Wizard Mishuta, was released by the Kemerovo Region Publishing House. With the proceeds from that book, she bought a typewriter.

In 2003, Tamara wrote another book, About Red-Haired Tayushka. The publishing house admired her talent but did not accept the story for publication saying it was too complicated and philosophical for children.

Then good luck intervened: a Muscovite, Olga Zaykina, read one of Tamara's fairy tales on the Internet and wrote a letter to the author, asking her where to find her other works. Tamara decided to send her the draft of Tayushki, and Olga liked it so much that she proposed publishing it and other tales online. Tamara was delighted that Zaykina was helping her not out of pity, but because she was moved by the depth and wisdom of Tamara's fairy tales.

Tamara types very slowly: she has only one functioning hand. But she continues to write fairy tales, essays for adults, and to correspond via social media and email.

Tamara's main advice to all people with special needs is to find a dream and follow it. Another thing that helped her to survive was that she learned to love herself and refused to consider herself a second-class person.

A lonely famous woman

Staff at the Novokuznetsk care home for the disabled, where Tamara is living now, treat her with respect, while fellow patients help her with her writing. Yet, Tamara has to hire two visiting nurses, who feed and dress her, and put her in a wheelchair.

“No matter how famous I become, I will forever be haunted by my disability. It is a cross that I am destined to carry till the end of my days. It is so humiliating to live in complete physical dependence on others...,” Tamara writes in her autobiography.

Fame has had no effect on Tamara's life: there are still days when she feels sad and lonely in the confines of her care home. She recently wrote a letter to a Russian TV channel asking for help for her relatives — their old house could collapse at any moment — but she got no reply.

That said, ordinary people write a lot to Tamara and admire her. “You know, it’s somewhat strange but healthy people write to me saying that my story inspires them and helps them to reconsider their lives and live on,” Tamara tells Russia Beyond.

Tamara at the Novokuznetsk care home

Personal archiveTamara wants to prove to everyone that people like her can achieve a lot in life.

In her autobiography, Tamara makes this emotional appeal to readers: "People! Healthy, normal, non-disabled, non-handicapped, who are able to walk on their own legs and use their own hands! Breathe freely and rejoice that you have been given this unbelievable treasure - the ability for independent and controlled movement! Consider yourself happy, as long as you do not depend on anyone! Do you not agree that having a healthy and able body constitutes happiness? Then at least agree that it constitutes a basis for happiness.”

If you want to help Tamara you can make a donation via Sberbank of Russia. Her card number is 5469 0200 1126 1253 (byline is Natalia Vasilenko). To contact Tamara please visit her website www.

READ MORE: ‘Children shout ‘invalid’ to my son – I won't tolerate this’: Instamother raises disabled issues

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox