This guy conquered 5 of the world's tallest peaks in 1 year

Vladimir Bashkirov in 1973, Caucasus

Personal archiveMountaineering was incredibly popular in the Soviet Union. As the cult

In the 1960s, after Yuri Gagarin’s flight into space, the USSR experienced a period of intense dreaming. And if space exploration was not open to everyone, climbing mountain tops was more accessible. Furthermore, mountains are a perfect place for dreamers.

‘I'm a very good climber’

Vladimir Bashkirov was a student at the Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology, which had one of

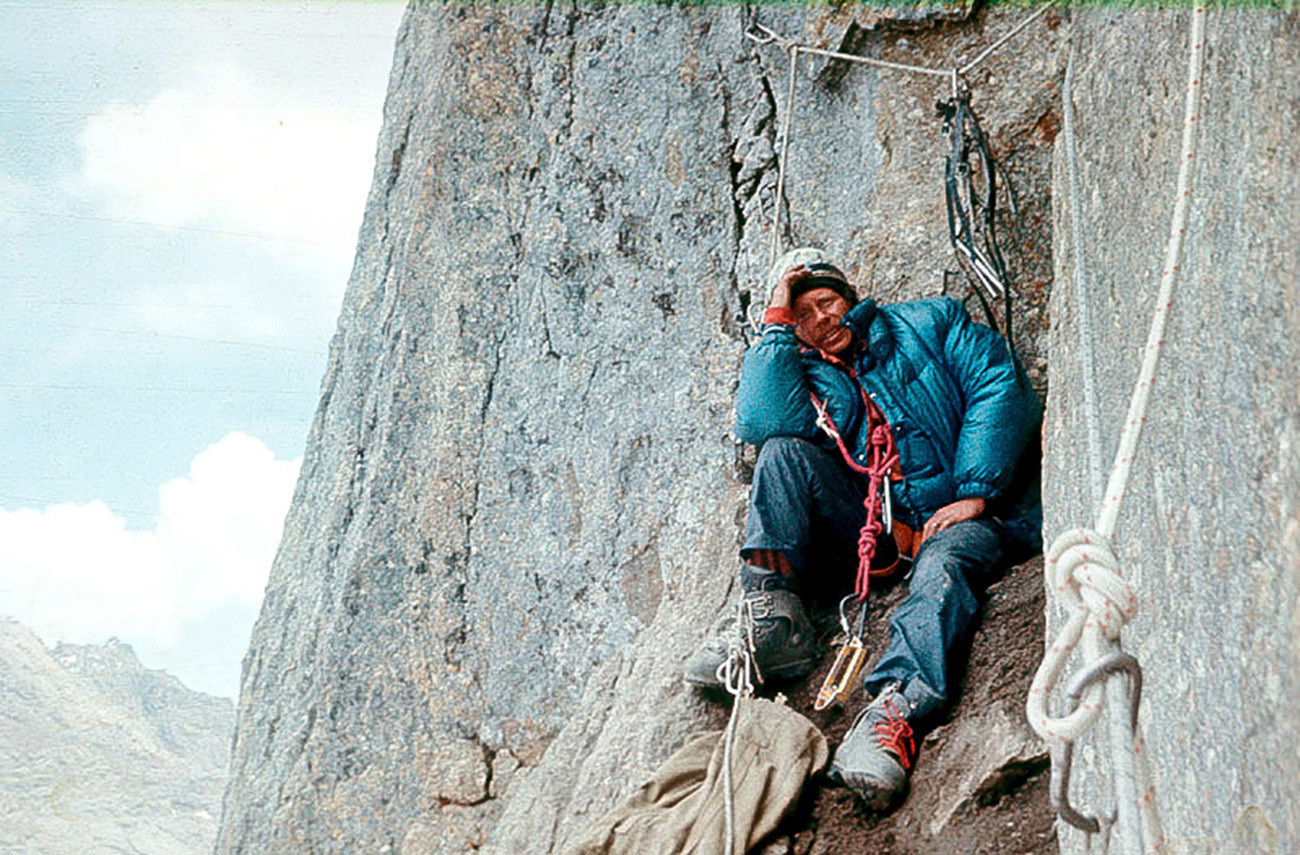

On a mountain wall

Personal archive“I do not have a high athletic rank but I am a very good climber,” he said. “You can send me anywhere, I will cope with any task.” And that's how the girl was saved.

Love in the mountains

His future wife, Natalya, was also doing mountaineering before they met, but not at such a serious level. In the summer of 1983, her friends at the Institute of Physics and Technology invited her to be their cook on a mountain expedition. She agreed, not sure why. “Perhaps, it was Fate,” Natalya said in an interview. And that was where they met

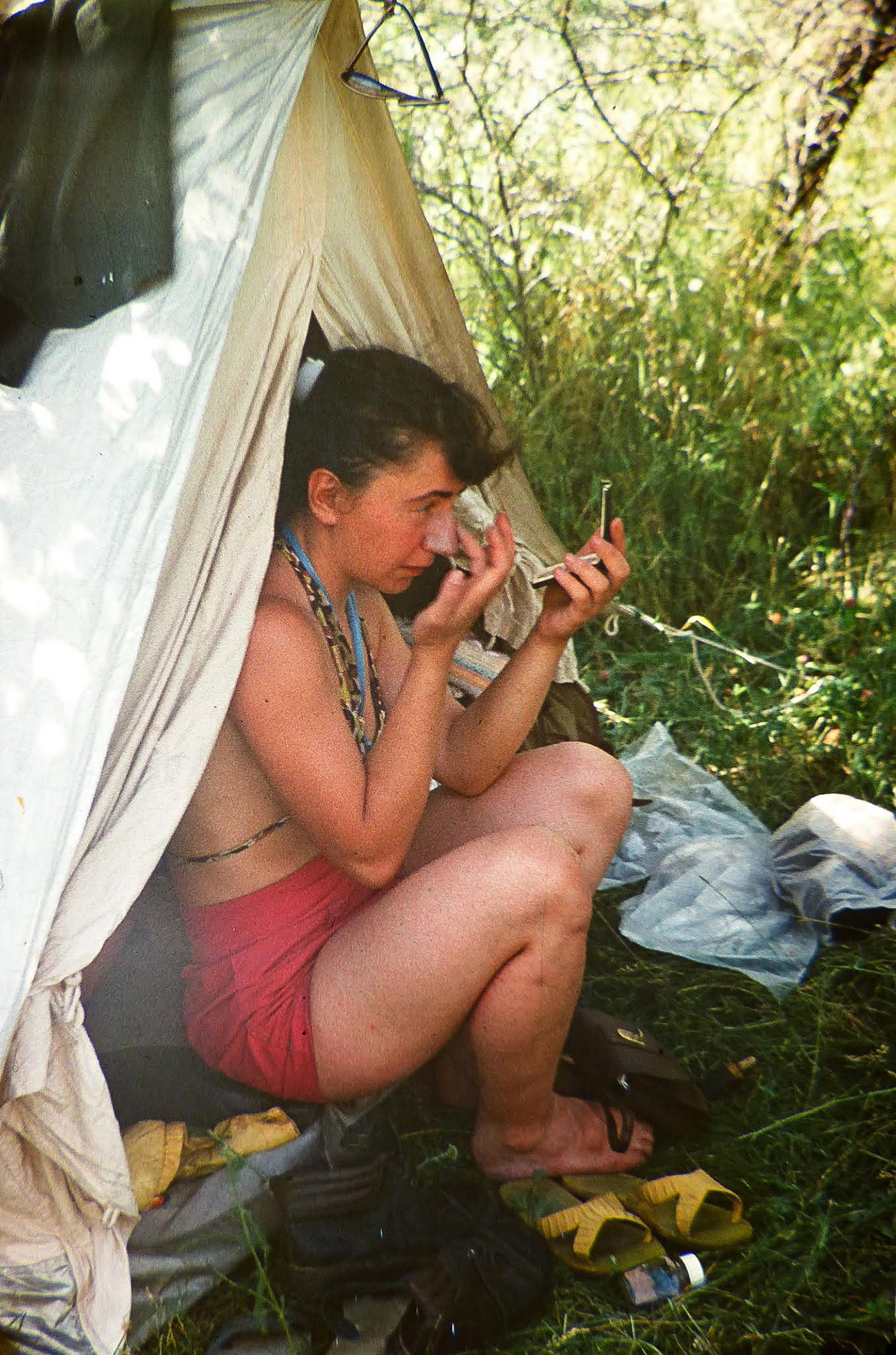

Bashkirov in 1983

Personal archive

Natalya Bashkirova

Personal archiveBashkirov was awarded the title Snow Leopard, given to those who had climbed all the highest peaks in the Soviet Union. From 1961 to the present day, only about 665 climbers have accomplished this feat.

‘People followed him’

Bashkirov climbed the summits, taking routes that no one had done before him. “He was attracted to the unknown,” says Natalya. She compares her husband to the legendary explorer Magellan, who was the first ship captain to circumnavigate the earth

Spartak sport society trainings

Personal archive“People who went climbing with him were fueled by his drive and his energy,” she adds.

Only once did Natalya and Vladimir climb a mountain together – it was the 4,000-meter high Ushba peak in the Caucasus. “When I saw that mountain my knees began to shake. It looked like a vertical, shining ice wall,” Natalya recalls. It was a long and difficult route, and on the way down, their small group was caught in heavy snowfall, lost their tracks and had to search for their way back in the dark literally by touch

Some peaks required spending nights in sleeping bags just like that

Personal archiveHimalayan peaks

Perestroika and the 1990s brought economic

His first trip was in 1991 to the Annapurna peak (8,091 meters), and in 1993, Vladimir decided to climb Mount Everest. Climbing routes there were booked months in advance, and his group received permission to climb only the western, long and gentler slope. That route could take a very long time and cost a lot of money.

At this time, however, a member of a women's expedition died on Everest and her relatives got permission for Bashkirov to climb the mountain via a different route because he had agreed to bring her body down. In the end, the woman's body was brought down by local sherpas, but thanks to the permission he had been given Bashkirov finally climbed Mount Everest. On his way down, he ran out of oxygen and was nearly exhausted but miraculously he managed to reach the bottom

Bashkirov in the Himalayas

Personal archiveAfter he climbed Everest for the second time, Vladimir’s clients, Indonesians, who had never even seen snow before then, invited him to Kathmandu to celebrate their achievement. He spent two weeks with them and completely lost his altitude acclimatization. Upon his return, he went up to the base camp in a matter of three days, although

Members of his team later told Natalya that Vladimir was not feeling well when they set off, and when they reached the top, things became really bad. The rescuer who arrived on the scene gave him a faulty oxygen cylinder. When descending, Vladimir's heart stopped. That was in May 1997.

Despite having lost her husband and several close friends in the Himalayas, Natalya continues to go to the mountains. An experienced guide, she leads trekking groups every

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox