Why do Russians adore May 1 so much?

A May 1st demonstration in Moscow.

Getty ImagesToday, May 1 in Russia is all about enjoying three or four days off (or even five, like this year), trips to the dacha, barbecues, and flights abroad for those who can afford it — a kind of nationwide annual leave. But at the beginning of the last century, things were much tougher. Workers went on May Day demonstrations to demand fair working conditions, often risking a bullet in the neck.

Day of workers’ wrath

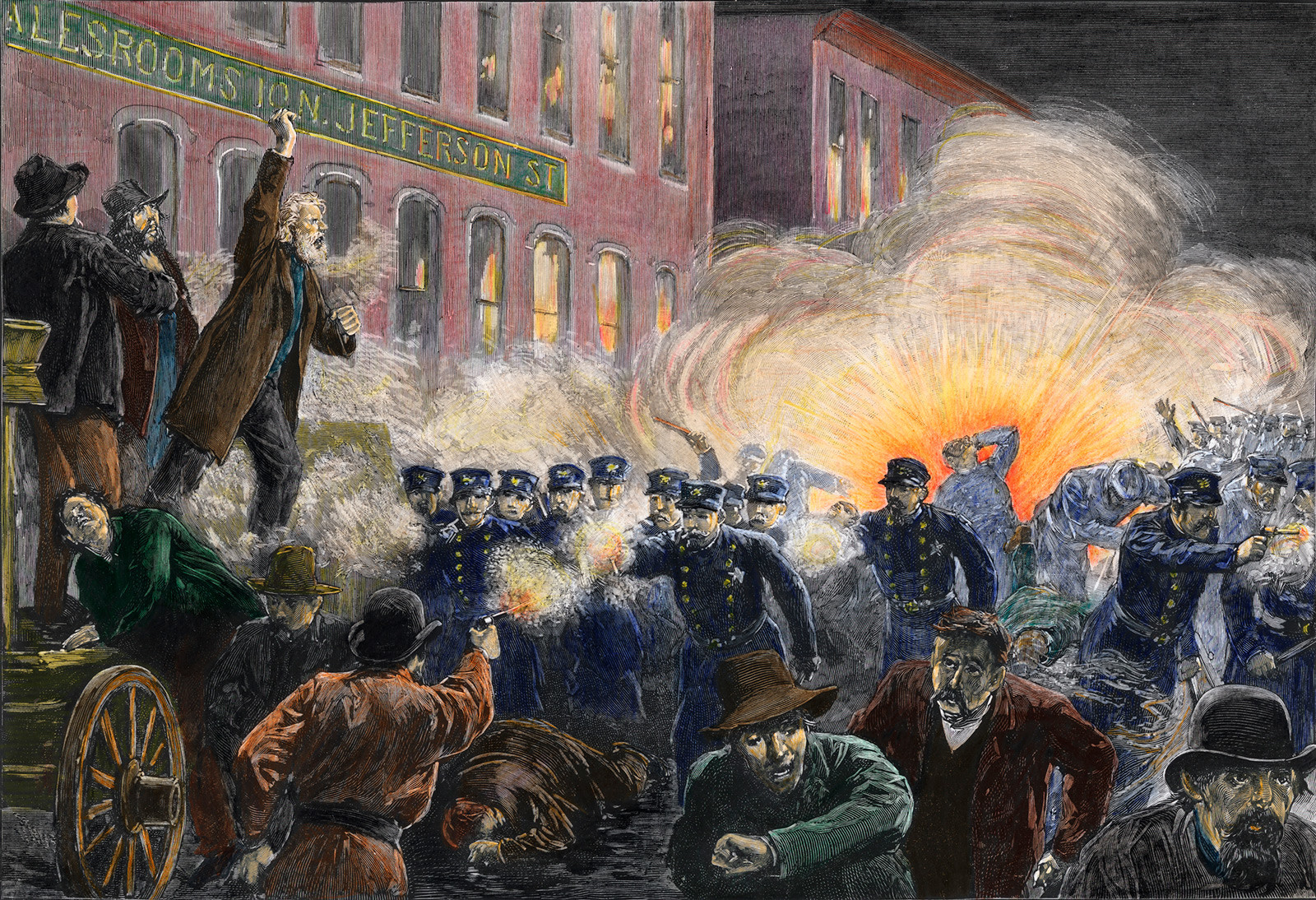

The Haymarket affair infuriated the international labor movement, making workers' struggle for their rights far more intense and brutal.

Getty ImagesMay 1 became International Labor Day after the tragedy at Haymarket Square in Chicago, Illinois, USA. In early May 1886, demonstrations were held in Chicago and other US cities demanding an eight-hour working day. It might seem a no-brainer today, but in the late 19th century many tycoons did not believe that workers had the right to sleep.

“No single event has influenced the history of labor in Illinois, the United States, and even the world, more than the Chicago Haymarket Affair,” wrote historian William J. Adelman. On May 4, a violent clash left four workers and seven policemen dead, after which a local court sent five activists to the gallows, despite their guilt not having been proven beyond all reasonable doubt. Three years later, the Second International met in Paris, attended by delegates from trade unions across the world, and recognized May 1 as Labor Day in honor of those who had died in Chicago.

From Chicago to Russia

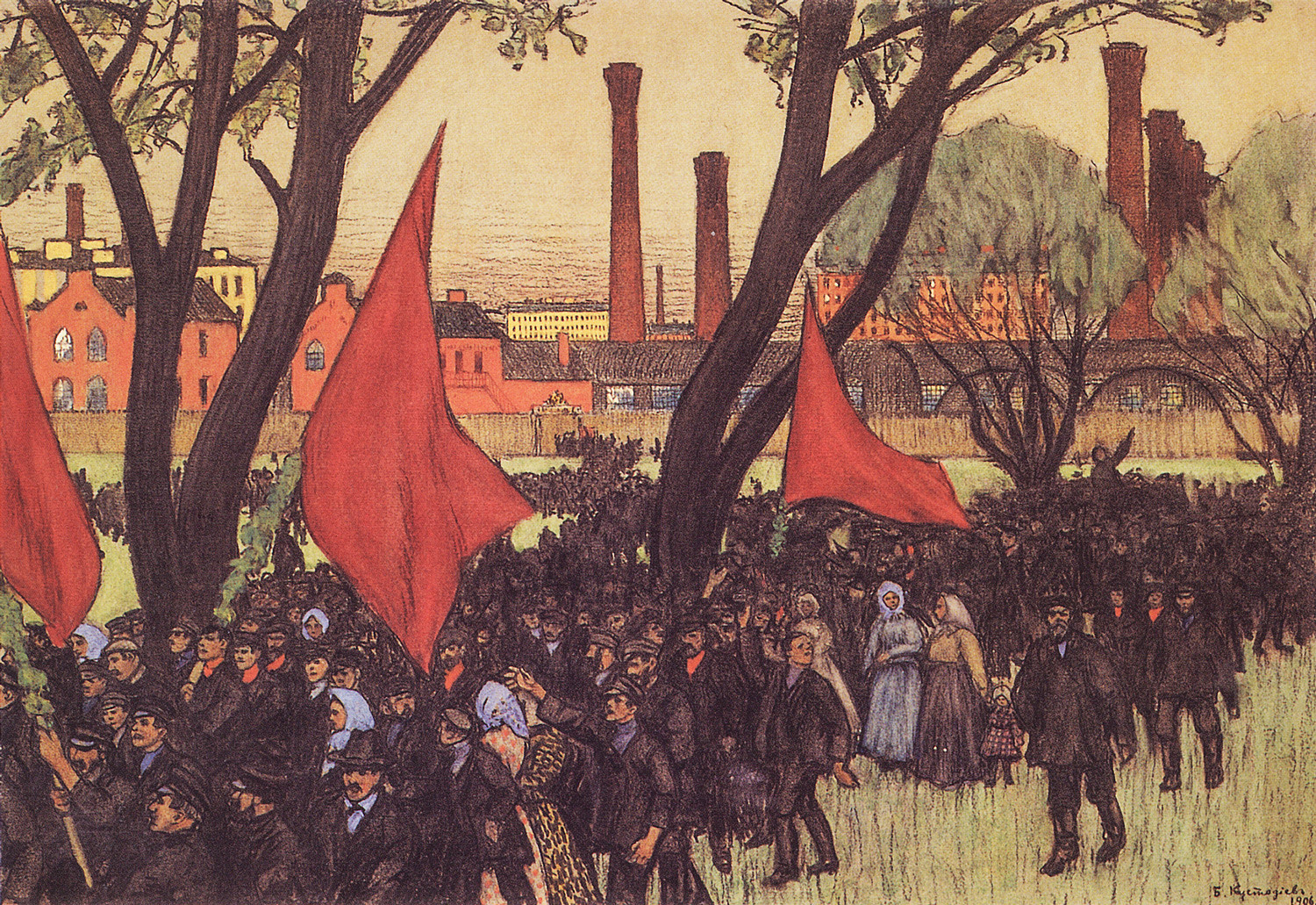

The May 1st demonstration of 1906, portrayed by a Russian artist Boris Kustodiev.

Back in Russia, where at the turn of the 20th century the labor movement was still in its infancy, the struggle between workers and authorities often had fatal consequences. Before every May 1, especially after the aborted 1905 revolution, the government feared mass strikes and assaults on the police and put heavy security measures in place. Revolutionaries, meanwhile, used the occasion to call upon workers to rise up against their bosses and the tsar.

In the Russian Empire, May 1 was not a holiday, of course. Factory owners threatened workers with dismissal for absenteeism that day. The threats, however, fell on deaf ears, and up until the outbreak of WWI the May demonstrations, strikes, and demands for an eight-hour working day and the overthrow of the autocracy grew louder and louder.

In 1914, a couple of months before the start of the war, the May 1 clashes were particularly brutal. “At 4 pm... the red banner was hoisted and Lubyanka Square resounded with revolutionary songs. Large units of enraged gendarmes and police moved against the demonstrators. There were scuffles, the workers began to pelt the gendarmes with stones…,” the newspaper Rossiyskaya Gazeta cites the memoirs of an eyewitness.

Soviet celebration

Vladimir Lenin (R) during the May 1st demonstration of 1919 in Moscow.

TASSThe Russian monarchy fell in 1917, but the first, so-called bourgeois revolution was followed later that year by the October Revolution, which saw the Bolsheviks seize power. The official stance on May 1 did an about-face literally overnight: it turned from being prohibited to obligatory. Vladimir Lenin himself spoke at the first May Day event, and in subsequent years only the anniversary of the revolution ranked higher in the hierarchy of celebrations.

In the early years, it was a military day of solidarity, during which socialist Moscow called upon workers of the whole world to unite and revolt against capitalism. “Prepare for an almighty battle, Comrade Workers. Stop the plants and factories on May 1, or take up arms...” Lenin urged in an article titled “May Day.” Gradually, however, the prospect of world revolution receded into the background, and May 1 turned into a typical holiday in an authoritarian country — with parades, processions, and praises sung to the nation’s wise leaders.

Spring holiday

May Day, 1970, in Moscow.

TASSNevertheless, May Day has always had a human dimension, far removed from the slogans about the inevitable victory of communism. Another perhaps more significant reason was that May 1 coincided with the arrival of spring after the long Russian winter, and Soviet people were inclined to celebrate the warm weather more than ideology.

“I simply adored the May Day holiday as a child. On that day, my grandparents always took me to see the demonstration. There were beautiful clothes, flags, balloons, smiling faces all around, sunshine, my grandfather with his camera...” reminisces a member of the group “Reportage from the USSR,” who grew up in the 1970s.

Although the USSR ceased to exist in 1991, May Day is still perceived as a very Soviet holiday. “They weren’t talking about workers’ solidarity, but about solidarity with parents, about how dad used to carry them on his shoulders, or how mom would lead them by the hand through the lines of factory workers,” wrote journalist Viktor Loshak after talking to participants in a traditional demonstration held in 2018. It makes sense. Today in Russia, there are no fights with police on May Day — this day of workers’ solidarity has turned from an ideological pageant into a feel-good spring holiday and an excuse not to go to work for a few days. Who would want to give up that?

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox