What’s it like to live in the LARGEST country in the world?

Big-city life in Russia, especially in the western part, is not much different from that in Europe or the U.S. But out in a Siberian village or the Far East, you’ll be amazed by the obstacles that locals have to overcome every single day.

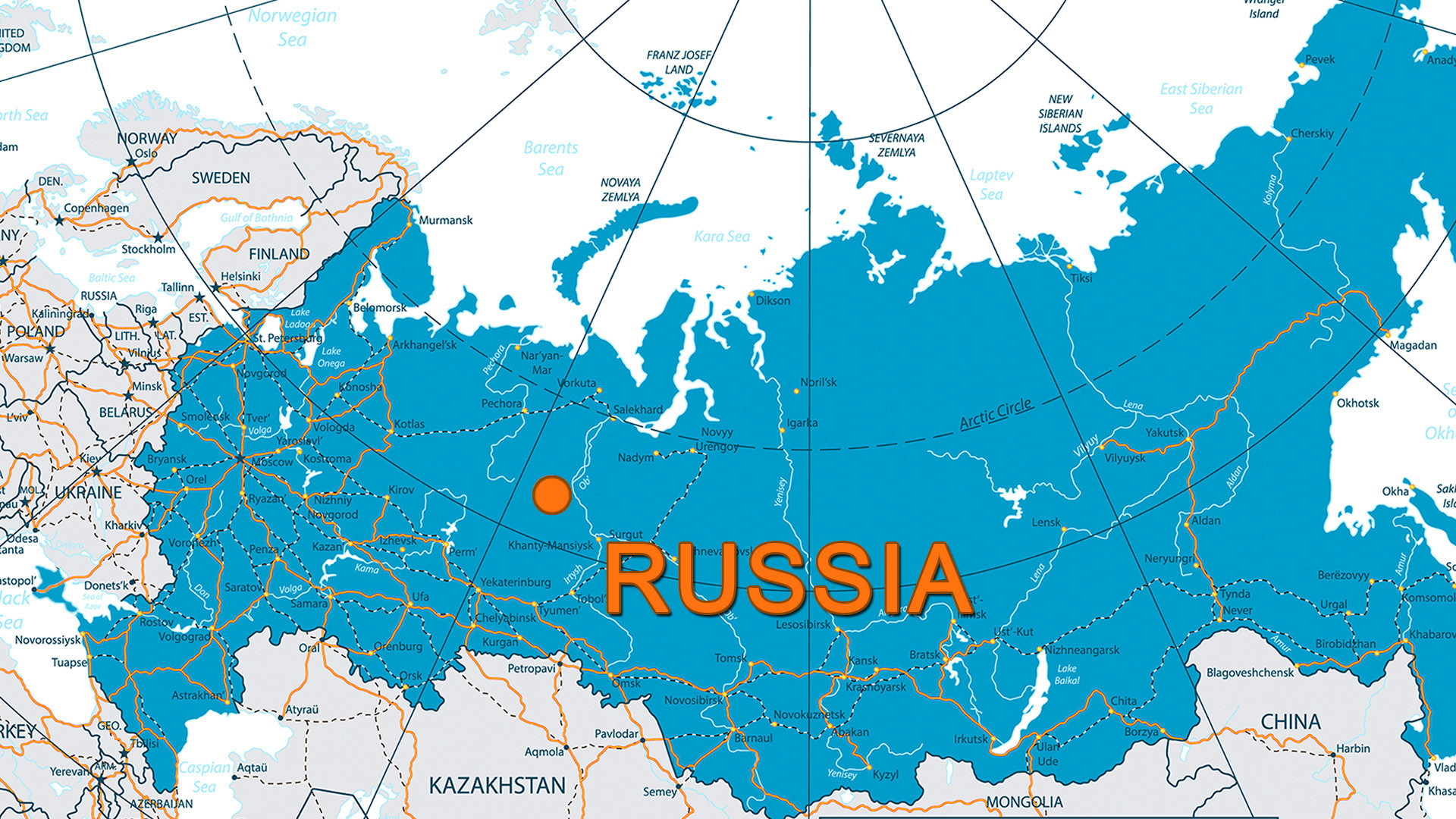

Breaking the bank to see your own country

Chersky.

ОЕ- LINA/youtube.comThe airport of the small polar village of Chersky in north-eastern Yakutia, with a population of no more than 2,500, consists of a two-story concrete box with a bright blue angular annex in the middle. The waiting room does not even accommodate 50 people, the local cafe is often shut, and Wi-Fi only appeared in 2020.

Even so, the Wi-Fi is rarely used, as there’s hardly anyone to use it. Why? Because the price of a one-way flight to the nearest city, Yakutsk (located in the same region, some 2,500 km away), costs 35–40,000 rubles (approx. $450–515). From Moscow to Yakutsk (8,200 km), a one-way flight will set you back 10,000 rubles ($130) and to Vladivostok (9,000 km), 13,000 rubles ($170) at flat fares (subsidized by the state and unchanged throughout the year; the number of seats is also limited).

“The last time I flew on vacation was a year ago to Gelendzhik (a resort town in southern Russia) with my family. One-way tickets per person cost 100,000 rubles ($1,300) in total and my monthly salary is several times less,” said Karina Khan-Chi-Ik, who works for the local administration. Karina would like to fly more often, but under the law, her employer pays all residents of the village for one flight only once every two years and she can’t save up for a vacation on her own.

The salary of another local resident, Victoria Sleptsova, does not extend to a hotel in a Russian resort, so she holidays in Yakutsk.

“Southern hotels are too expensive for me, especially in summer, and the planes are uncomfortable — on a 4-hour flight they give you only water and snacks,” Sleptsova complains.

The Ryazan Region.

@natali.v.popovaEven some Muscovites cannot afford to travel around Russia. Travel blogger Natalya Popova has been to 43 countries and visited 23 regions of Russia (there are 85 in total) in the past five years, but some places in Russia are still inaccessible to her, not geographically, but financially.

“I started traveling around Russia during the pandemic, as there was no choice. From Moscow, you can fly quite cheaply to nearby popular cities like Kazan, St Petersburg, Rostov-on-Don, Yekaterinburg and Samara. But the most beautiful places in Russia, such as Baikal, Kamchatka and Sakhalin, are too expensive and I can’t afford them yet,” explains Popova.

The Northern lights in Dikson.

Robert Praszenis/SputnikTraveler and blogger Maria Belokovylskaya agrees. When I exchanged messages with her, she was in Dikson, one of the northernmost villages in Russia.

READ MORE: 10 facts about Russia’s northernmost settlement

“This is a tiny settlement in the Arctic desert with a population of 300. Flying one way there cost me 70,000 rubles ($905) — for the same money you can get to Botswana in Africa. I don’t regret the choice, but for Russians, tickets even to far-flung places in Russia should be cheaper,” Belokovylskaya is sure.

Long distances to school

The Vologda Region

https://newsvo.ru“Sanya, hang on!” shouts a woman filming a man on her phone, who is breaking the ice with a shovel so that their boat can keep moving. This is how Leonid Khvatov, a resident of the village of Pakhtalka in Vologda Region (527 km from Moscow), sees off his two sons to the nearest school — first by boat across a river, then 2 km on foot across a field. The local administration refuses to build a bridge, due to lack of finances, and a school bus is also not an option because there is no road.

“In the spring and the fall, children walk waist-deep in mud and in winter often waist-deep in snow, because the so-called road goes right through a field. <...> The children cross the river two times a day. In winter, there’s an ice crossing, and in the fall and spring, my wife and I transport them by boat. <...> At certain times of the year, we can’t get medical or other assistance because of this,” Leonid Khvatov told Vologda news web portal NewsVo.

For Russia, such situations are more the rule than the exception. Every fall and spring, news reports appear about children in this or that village not being able to get to school. For instance, during the coronavirus pandemic this spring, primary school teacher Svetlana Dementyeva from Kursk Region (524 km from Moscow) walked 7-8 km to take homework to self-isolating children living in houses without Internet access.

Tver Region.

Kombinat Blagoustroystva/youtube.comChildren from the village of Krasnaya Gora in Tver Region (614 km from Moscow) also face a difficult journey to school, says a Russian forum user with the nickname ‘Olgard’.

“I walked to school for four years, 8 km there, 8 km back. It was nothing, only we had to hide from wolves in winter and wade through mud in the fall and early spring. Sometimes I cycled there in winter and fell off about 15 f***ing times — the road was really slippery,” he recalled.

He says that some kids rode to school on a farm vehicle or bus, which often broke down along the way. In high school, his father took him there by tractor, and later, buses were provided.

“Now, there are more wild animals around, so it’s really dangerous to let children walk. But the scenery is stunning,” he muses.

No mobile signal or Internet

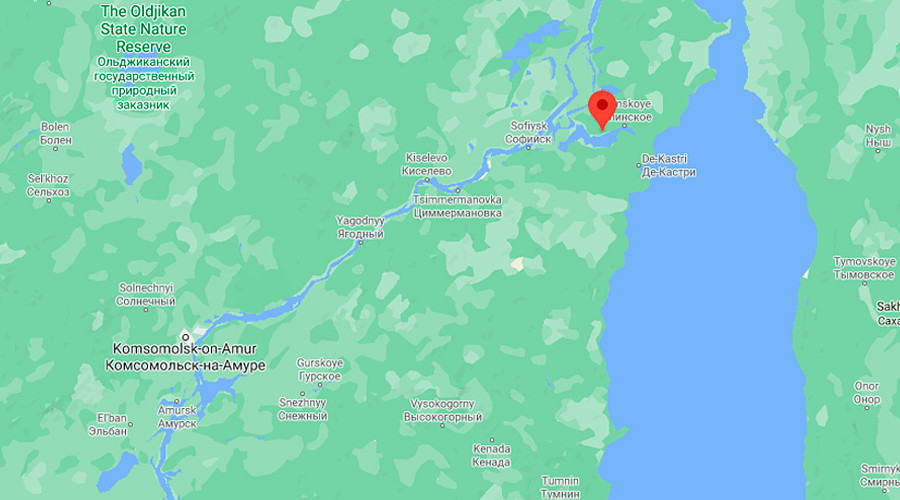

Bolshie Sanniki village.

Google MapsIn 2020, it takes just a few clicks to send a meme to a friend, find information you need, or watch a movie. But for 43-year-old Alexander Guryev, a resident of the village of Bolshiye Sanniki in Khabarovsk Territory (8,900 km from Moscow) with a population of no more than 400, things were never quite so easy.

Every time that Guryev wanted to surf the Internet, he got dressed, jumped in his car and drove about 700 km (8-12 hours) to the nearest city of Khabarovsk with its mobile coverage. This was the case until the fall of 2020, when the village finally got its own Internet connection.

“I wasn’t that hooked on the Internet, but, still, I couldn’t make a doctor’s appointment online like ordinary people, it was a pain. At home it was boring — I went fishing and mushrooming, the neighbors took to drinking. Now, at least, I can go on VK (a popular Russian social network),” says Guryev.

The village of Salba in Krasnoyarsk Territory (4,200 km from Moscow; population no more than 200) had no Internet or mobile coverage until March 2020. Local resident Marina (not her real name) claims that the village did just fine without it.

“Do you have any idea of what rural life is like? We have practically no time off, only work. You only need the Internet to keep in touch with relatives. We’re doing OK as we are,” asserts Marina.

In 2019, residents of more than 25,000 Russian settlements with a population of 100–250 managed without Internet and mobile coverage. How many remain offline in 2020 is unknown.

More often abroad than in Moscow

Kaliningrad.

Legion MediaGetting in the car and driving to Poland or Germany for shopping or leisure (not forgetting one’s passport with Schengen visa, of course) is an ordinary weekend for Russia Beyond author Ekaterina Sinelshchikova, who lives in Kaliningrad.

“Before the sanctions in 2014 [when a food embargo was introduced against Russia], we regularly traveled to Poland — we crossed the border, drove to the nearest supermarket a couple of kilometers from the border zone and stocked up on food. It worked out cheaper that way, even taking into account gasoline. After 2014, we didn’t stop going, but went there less often. When we did, I hid Polish goods in my handbag,” Sinelshchikova recalls.

Ekaterina says that it was quicker and easier to get to Europe than to Moscow — everyone went to Europe for the New Year vacation and 2–3 day tours to European castles and water parks were especially popular. At the same time, as she explains, many still dreamed of living in the capital and escaping from their provincial city, even if it was close to Europe.

“But having lived in Moscow, you start to see the pros of the former cons of Kaliningrad. Many people I know eventually returned. You start to appreciate the local forest, the sea, the open space — there’s nothing like it in Moscow,” says Ekaterina. “Plus, you’re never short of company — just walk into a local bar and you’re sure to see a friend, colleague or former classmate. You don’t have to make plans a week in advance, everything's simpler.

Vladivostok.

Legion MediaVladivostok resident Dmitry Chalov, 55, a former rescue ship diver, spent most of his life in various cities in China and Japan. He first went to China in 1995, when working as an ordinary seaman towing ships to China and Japan for sale.

“I was 30 years old and had never seen a city of such size. And best of all for us sailors was the main shopping street, which could be anything from 7 to 17 km long. There were all kinds of goods, cafes selling frogs and snakes, home equipment that seemed to have come from outer space,” recalls Chalov.

Later, he started vacationing in China, Japan, Thailand and Vietnam every year, paid for by the state, since he worked in the rescue service.

“Here we have sea, nature and foreign countries closer than our own capital. What’s Moscow? A sack of concrete, nothing more,” sums up Chalov.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox