What they teach at the ‘Russian Santa’ academy

Murod in the costume of Grandfather Frost.

Shaytanka.ruIn everyday life, Murod Idiboyev, a 27-year-old resident of Yekaterinburg, teaches English and works part-time as a waiter. But in the last week of December, he puts on a red or blue robe and a hat with a white trim, takes a huge sack of presents and goes to see children and adults who have less fortunate lives than other people. Like hundreds of other volunteers, Murod graduated from the Akademiya Dedov Morozov (Academy of Grandfather Frosts) as part of the 'Wishing New Year Tree' project. It was set up by charity organization Dorogami Dobra ('Paths of Kindness') to help children with disabilities and children from orphanages and troubled families, as well as veterans of the Great Patriotic War. Since its inception, the number of volunteers has gone up several fold, so that it has even become necessary to open special courses to train Grandfather Frosts and Snegurochkas (Snow Maidens).

Santa from the East and Snow Maiden from a bank

For Murod, it will be his fourth year playing the role of the New Year wizard. He decided to become a Grandfather Frost back in 2016, when he had just moved to the Ural capital from Tajikistan. “I’ve always enjoyed helping people,” he explains. “I also take part in subbotniks [voluntary work] to tidy up the streets and I give free English lessons to pensioners. And then someone told me that there was an opportunity to bring joy to children and veterans.” Murod says that, initially, he felt self-conscious, because of his poor knowledge of the Russian language, but it turned out that for children this wasn’t that important. “When I was little, I was also visited by Grandfather Frost and, although I knew it was my uncle, I still looked forward to seeing him every year.” At the Academy, Murod learned the intricacies of communicating with children. “For instance, you can’t tell a child to listen to their parents, because the child may have no parents,” he says. Also, volunteers aren’t allowed to use their smartphones and should always stay in character when playing the wizard. And they must always hand out presents.

Grandfather Frosts deliver presents throughout Sverdlovsk Region until December 30 and they often find out where they have to go only on the day of the trip. It could be a satellite town outside Yekaterinburg or some small village on the periphery of the region. They work in tandem with their Snegurochka “granddaughters”.

Oksana will be Snegurochka for the first time this year.

Personal ArchiveOksana Abroskina, a bank employee from Yekaterinburg, will be Snegurochka for the first time this year. “I’ve always wanted to help children and learned about this opportunity from a girlfriend of mine who has been doing voluntary work for Paths of Kindness for a long time now,” she says, adding that she can’t wait to try on her Snegurochka costume.

“I would like all children to have a celebration and for everyone to believe in fairytales and miracles,” she says.

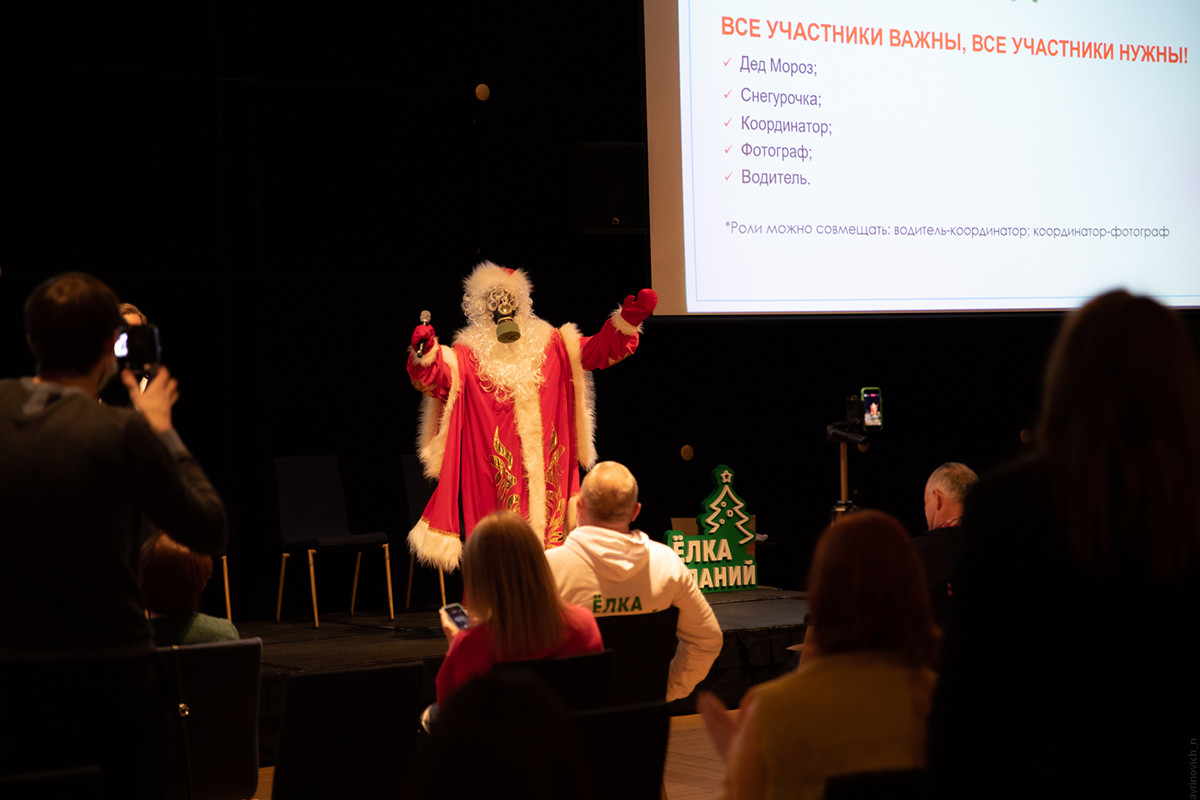

At the Academy.

Personal ArchiveAnd in every home, children can’t wait to meet their New Year guests, in order to receive their presents and to recite a poem for them.

“One day I had ‘In Lukomorye a green oak stands…’ [a famous poem by Alexander Pushkin] recited to me several times in a row, so by the end of the day I was craving to hear just the little verse ‘The Forest Raised a Christmas Tree’ [the most popular children’s New Year song in Russia],” recalls Murod.

Fairytale for grown-ups

This year more than 3,000 children from orphanages, troubled families and children with disabilities, are to receive presents, says the creator and organizer of the Wishing Tree project Valery Basay. “We have been training Grandfather Frosts and Snegurochkas for almost 10 years now as part of our Wishing Tree project,” he says. “Training is split into two stages: acting skills for future wizards and training in dealing with children and adults in a crisis situation. How should you behave when you encounter alcoholic parents? How to talk to a child with cerebral palsy?”

Entry to the academy is allowed from the age of 18. There is no upper limit - one of the Snegurochkas was 82. But the average age of volunteers is from 30 to 50.

In addition to Grandfather Frosts and Snegurochkas, the Academy also trains their forest helpers - Belochka, Zaychik and Snezhinka (Little Squirrel, Little Hare and Snowflake). These are also volunteers: One person takes souvenir photos of the meeting with Grandfather Frost, while someone else helps to carry his sack of presents.

In order for their wishes to be fulfilled, children have to write a letter and send it to the organizers. Wishing Tree officially starts in September and ends on Dec. 20 to give the volunteers enough time to distribute presents to everyone. The collection of presents is a joint effort: Some are donated by organizations, and some are purchased by ordinary people. New Year trees decorated with postcards with children’s messages are installed in grocery stores in Yekaterinburg and Sverdlovsk Region. To make a child’s New Year wish come true, all that is needed is to buy the requested present and hand it to a member of the store staff, quoting the number of the card. As a rule, the sorts of presents that children ask for are the most ordinary things, costing no more than 2,500 rubles (approx. $50), although there have also been curious requests.

“One little girl asked us for a toy cat,” Valery recalls. “We rang her father and he admitted that she had wanted a real one, but her mother was against it. Our volunteer who was distributing presents brought both a real kitten and a toy one, saying he had not understood which was required. And Grandfather Frost first gave the girl the toy and then asked her whether she believed in magic and asked her to blow. She blew and a real ginger kitten appeared in her hands. The little girl saw the world in the brightest of colors and her happiness was immeasurable.”

At the same time, the presents can also be very expensive when the organizers see that a child needs a laptop for school work, for example, or an exercise machine for physical rehab.

In addition to children, the volunteers will also bring greetings to veterans and concentration camp survivors - members of staff prepare these presents themselves.

“During the years we have been operating, Wishing Tree has become so popular that a similar event is also being run now in other Russian towns - Chelyabinsk, Samara and Kaliningrad,” Valery says. “And we have realized that all of this is not just for the children, but also for adults who, in the run-up to New Year, want to play their part in a big miracle. In every Russian fairytale, the main hero has loyal friends. That's because a fairytale occurs when we are many. And together we can work a miracle and make not just children happy, but also grown-ups.”

Grandfather Frosts in respirators

Because of the coronavirus pandemic volunteers are going to have a somewhat unfamiliar appearance: New Year wizard costumes are going to have added face masks, protective visors and even respirators. Grandfather Frosts intend to bring joy to children and the elderly even if they are ill, Valery explains. “Everyone knows that Grandfather Frost has a magic staff. It is a meter and a half long and this year, Grandfather Frost is going to be telling people not to approach within a ‘staff’s length’ so that his greeting is conducted safely,” Valery says.

In Sverdlovsk Region, as in many other regions of the country (and the world), many New Year events have had to be cancelled, including in kindergartens, but graduates of the Academy of Grandfather Frosts promise that no-one will be left without festive cheer this year.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox