How did Romanov family jewelry wind up in the United States?

The wedding crown of the Romanov dynasty, from 1884 to 1953. Now it's a museum artifact.

Public domain; Vogue, April 15, 1953; Miss Universe OrganizationFollowing the 1917 Revolution, the Bolsheviks sold the Romanov family’s treasures off to international buyers while keeping only the most valuable pieces in Russia. This luxurious jewelry collection appealed not only to the tastes of European monarchs but also American socialites and famous jewelry houses.

Maria Pavlovna's Emeralds

Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna (1854-1920), the spouse of Vladimir Alexandrovich (son of Emperor Alexander II), was one of the few Romanovs who managed to take her jewelry abroad after the revolution. She had a large collection of jewels that she was able to bequeath to her children after the death of her husband. This parure of huge emeralds became famous thanks to photographs of a Romanov costume ball in 1903. In them, Maria Pavlovna poses in the costume of a boyarynya (a noble woman in ancient Russia), and her headdress and gown are adorned with an emerald diadem and brooches. What’s more, these stones used to belong to Catherine the Great. This and many other diadems from the time were adaptable and could be worn as necklaces, brooches or earrings. The Grand Duchess received the jewelry as a wedding present from Alexander II in 1874.

Maria Pavlovna during the 1903 ball and her emeralds.

L.S.Levitsky; Archive photoHer son Boris inherited the emeralds. Initially, his wife Zinaida Rachevskaya wore them, but he later sold them to the Cartier jewelry house. Boris used the proceeds to purchase an actual castle not far from Paris.

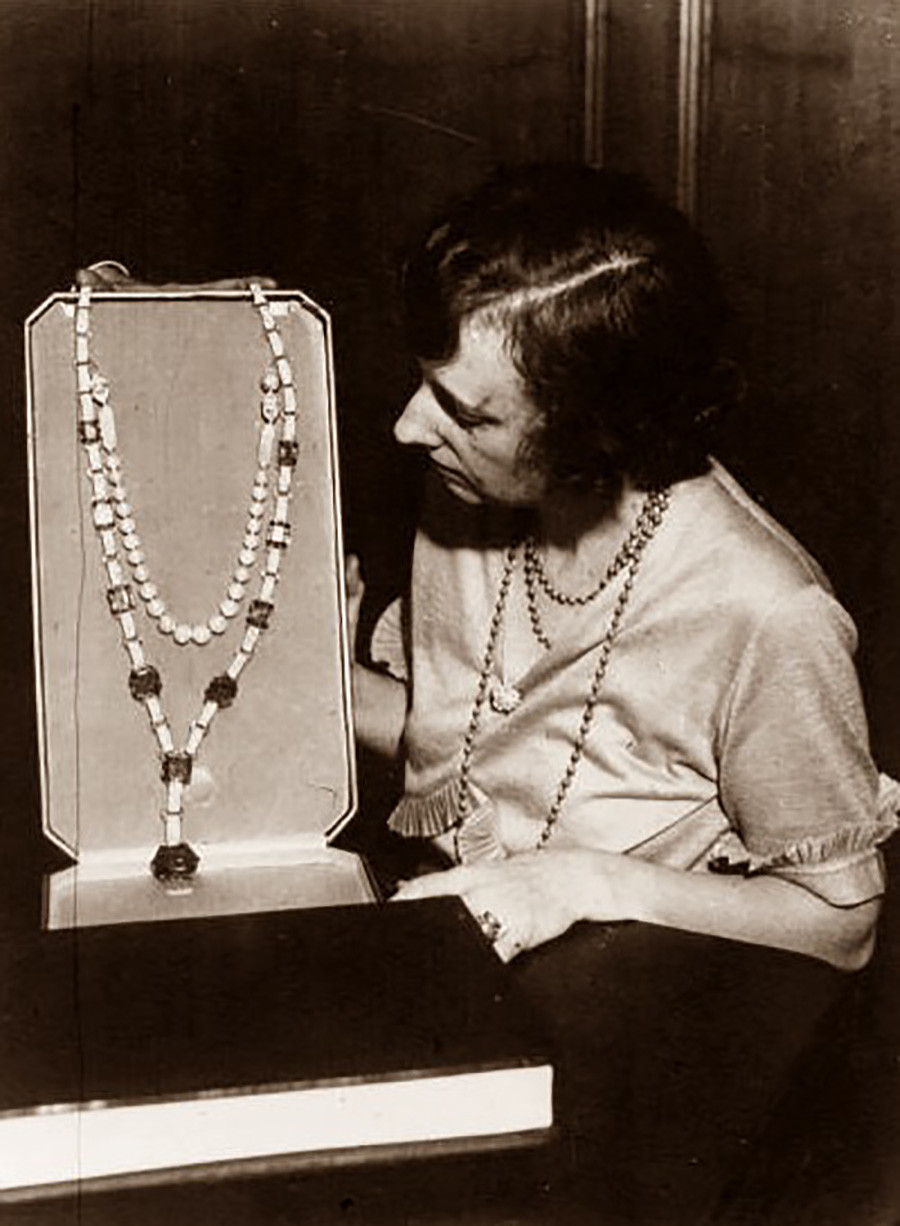

Zinaida Rachevskaya in Maria Pavlovna's emeralds.

Public domainMeanwhile, Cartier used the historic emeralds to make new jewelry and that was resold to private owners. For instance, some of the stones were reset in a sautoir (a necklace with pendants) made to order for Edith Rockefeller, the daughter of Standard Oil founder John Rockefeller. After her death, the jewelry was repurchased by Cartier for reworking.

A sautoir with Maria Pavlovna's emeralds.

Archive photoOne of the most famous tiaras set with these stones belonged to the socialite Barbara Hutton, an heir to the Woolworth retail empire who squandered her entire fortune by the time she died.

After Hutton's death, the tiara was taken apart and some of the stones were (according to some sources) reset by Bulgari in an emerald parure for the actress Elizabeth Taylor. These too were sold at auction.

Left: Actress Liz Taylor in her emeralds, 2003. Some of those gems were from Maria Pavlovna's parure. Right: The imperial emerald from Maria Pavlovna's parure cut by Cartier in 1954 and turned into this necklace.

Getty ImagesThe largest emerald was later recut into a drop shape by the Cartier jewelry firm—losing a third of its weight in the process—and reset in a diamond necklace. In 2019, it was sold at auction for over $4.8 million to a private buyer.

The Romanov Nuptial Crown

Princess Elisabeth of Saxe-Altenburg and a Cartier model in Romanov wedding crown.

Public domain; Vogue, April 15, 1953This small crown studded with large diamonds was made in 1884 for the wedding of Elizabeth Feodorovna and Sergei Alexandrovich, son of Emperor Alexander II. All subsequent members of the Romanov family, right up to the Revolution, wore this tiara at their wedding. However, the Bolsheviks didn't see any particular artistic merit in it and decided to sell it at auction. It has changed owners several times (the crown even adorned the head of the winner of the Miss Universe contest in California in 1952!) before 1966, when it was bought by Marjorie Post, the wife of the former American ambassador to the Soviet Union. A great admirer of Russian art, she founded Hillwood Estate, Museum and Garden outside Washington, and the crown became its most valuable exhibit.

Catherine the Great's Pearl Necklace

The necklace of Empress Catherine the Great (1729-1796) initially consisted of 389 natural river pearls. Artificial pearls did not exist until recently, and it was a very rare and expensive gem that few people could afford. After the revolution, the necklace ended up in possession of the Cartier jewelry company and was then sold to the American automobile magnate Horace Dodge. In 1920, he acquired it for his wife, Anna Thompson Dodge, for $820,000—an incredible amount of money at the time.The jewelry was divided up in the inheritance of their five grandchildren, each of whom received one string of pearls. In 2018, three strings of the pearls, held together by a diamond clasp by Cartier, were sold at auction in New York to a private buyer for $1.1 million.

Maria Feodorovna's sapphire

Maria Feodorovna in her famous parure and Ganna Walska.

Archive photoEmpress Maria Feodorovna (1847-1928), the consort of Alexander III and mother of Nicholas II, the last Russian Emperor, managed to flee to Britain after the revolution (her sister Alexandra was the consort of King Edward VII) and then to Denmark, where she had resided before her marriage. After her death, the pieces of jewelry were passed to her daughter Xenia, who began selling them off. The Empress had a soft spot for sapphires, and her collection included some very large and rare stones—some of which are still worn in Britain today). The largest sapphire ended up in the New York jewelry workshop of the Cartier firm in 1928, which subsequently sold it to the American opera singer Ganna Walska (who was born in what is now Belarus). In 1971, the diva decided to sell her jewelry and, after a string of owners, the sapphire came back to Cartier again.

In 2015, its jewelers created the Romanov bracelet with Maria Feodorovna's 197.8 carat refaceted sapphire. The identity of the new owner has not been revealed.

Jewels of the last Romanovs

A collection including Fabergé jewelry (including a number of celebrated Easter eggs), ancient Orthodox Church icons, cross pendants that once belonged to the daughters of Nicholas II, refined porcelain tableware and many other Romanov personal possessions was taken out of the USSR by the American entrepreneur Armand Hammer, the great grandfather of Hollywood actor Armie Hammer. Armand Hammer's father was one of the most famous American communists and even named his son in honor of the "arm and hammer" emblem of the Socialist Party of America. Hammer collaborated with the Bolsheviks for a number of years and was involved in Soviet military intelligence missions (more on his Soviet years here)

During that time, he managed to piece together quite a large collection of Russian art, which he was permitted to take out of the country in the 1930s. The precise number of items that ended up in the hands of enterprising Americans is unknown. Some historians believe that many of the items had little artistic value and that some of them were downright fakes, but in 1932 Hammer held a veritable clearance sale of tsarist treasures in a New York antique shop. They included Fabergé Easter eggs, a Fabergé cigarette case, Nicholas II's personal icons, and Maria Feodorovna's notebook among many other things. Some of the Romanov valuables were listed as "Urals stones," so it is very difficult to trace what later happened to them. Individual items of jewelry still turn up at vintage auctions today.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox