What is ‘muzhik’ in Russian, and why is it cool to be one?

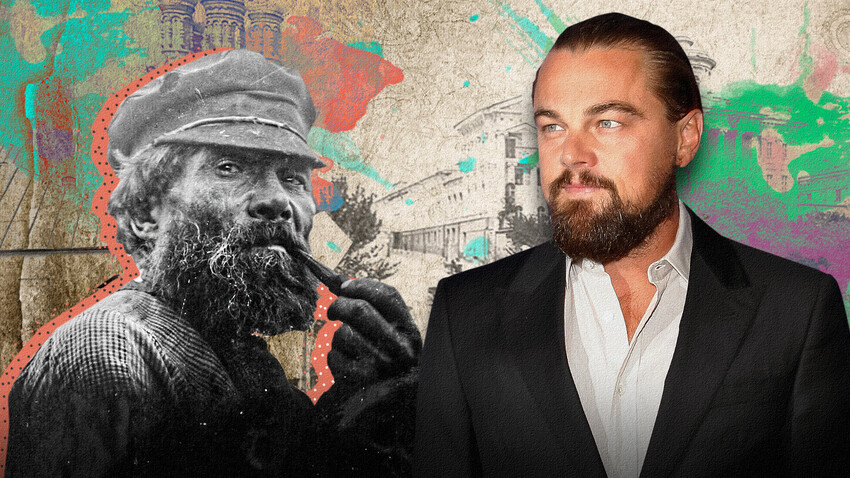

In 2010, Russian President Vladimir Putin called Leonardo DiCaprio a “real muzhik.” What he meant was that Leo, while traveling to St. Petersburg to attend a conference on saving endangered Amur tigers, had to change three planes. DiCaprio’s plane from New York had to turn back after an engine burst into flames. His second private plane was then diverted to Finland due to a snow storm.

In a speech, Putin said DiCaprio “broke his way through to us as if he were crossing a front line.” Continuing, the Russian president said: “I am sorry for the mauvais ton, but in our country we call people like that ‘a real muzhik’.

Who could be considered a “muzhik” in Tsarist Russia?

Leonardo DiCaprio in "Revenant," 2015.

Alejandro G. Iñárritu, 2015 / Regency EnterprisesIn almost all media coverage of the event, Putin’s words about DiCaprio were translated as “a real man.” But that’s not altogether accurate. The phrase “real man” would in fact be translated as “настоящий мужчина” (“nastoyashiy mujchina”), where мужчина is the exact translation of “man.” Muzhik, however, is something different.

In Italy, the word paesan is something similar to “peasant” in English – an unskilled agricultural laborer, roughly equivalent to fellah in Egypt. Both of these words can also be used in their respective cultures to mean “buddy” or “dawg.” Well, that’s the first, basic meaning of a muzhik in Russian – one who belongs to peasants, agricultural workers etc. In Tsarist Russia, the word muzhik was used to mean a man belonging to the peasant social stratum – even in official laws and documents.

In colloquial speech, muzhik in pre-revolutionary Russia was a social term, but in a nobleman’s speech, it took on derogatory overtones: a nobleman calling another nobleman a muzhik was considered a grave insult, and would almost certainly result in a duel.

A “bufetny muzhik” could mean a canteen servant, a “dvorovy muzhik” meant a servant in a nobleman’s estate, and so on. However, there was always a more complimentary and even honorable side to this word – and that’s how it’s mostly used in contemporary Russian.

What’s the difference between a man and a “muzhik”?

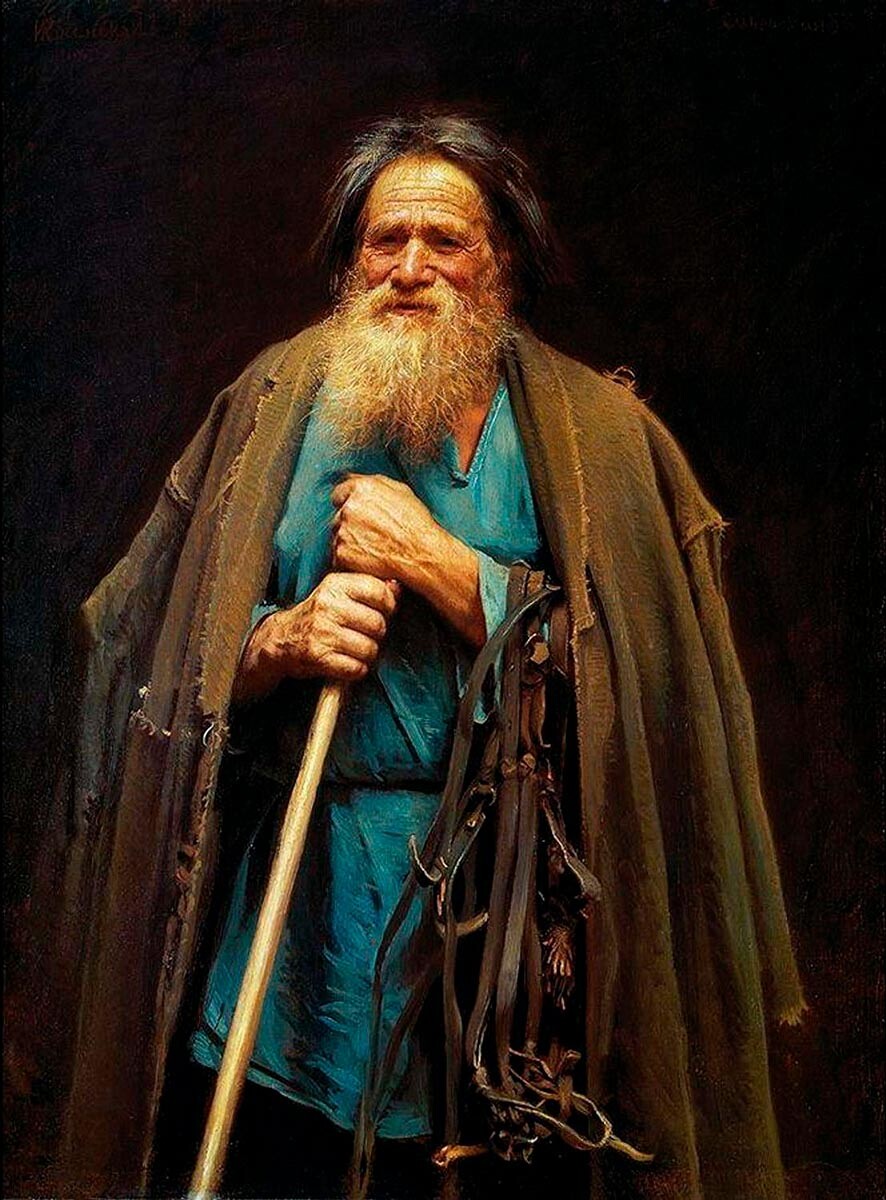

"A peasant with a harness," Ivan Kramskoy, 1883.

Kiev Art Gallery / Public DomainRussians always admired their own peasants – the majority of the population and the winning power behind all the victories of the Imperial army. Since the times of Empress Elizabeth (1709-1762), Peter the Great’s daughter, “balls with muzhiks” were being organized in the Winter Palace shortly after New Year – which meant everybody, even peasants (if cleanly dressed) were allowed to attend.

It might also surprise you that, in his private life, Emperor Nicholas I of Russia used to call himself a muzhik (and his spouse, Empress Alexandra – “my baba” (the same word for “a peasant woman”). Using these words, the Emperor praised the idea of a Russian muzhik – a relentless, fearless and decisive person, who would do anything to defend and provide for his fatherland, home and family.

This meaning remained unchanged throughout the ages, and it’s still used now. What do we, Russians, mean when we call someone a real muzhik?

First, he’s distinctly masculine. He doesn’t necessarily wear a beard, but he can certainly be a bit rude. A bit reserved. A muzhik is definitely tough – physically and mentally. He doesn’t, however, need to be a jacked athlete. For example, the late genius Stephen Hawking was definitely a real muzhik – for overcoming his disease and becoming one of the greatest scientists we ever knew.

READ MORE: 7 reasons why Russians are so tough

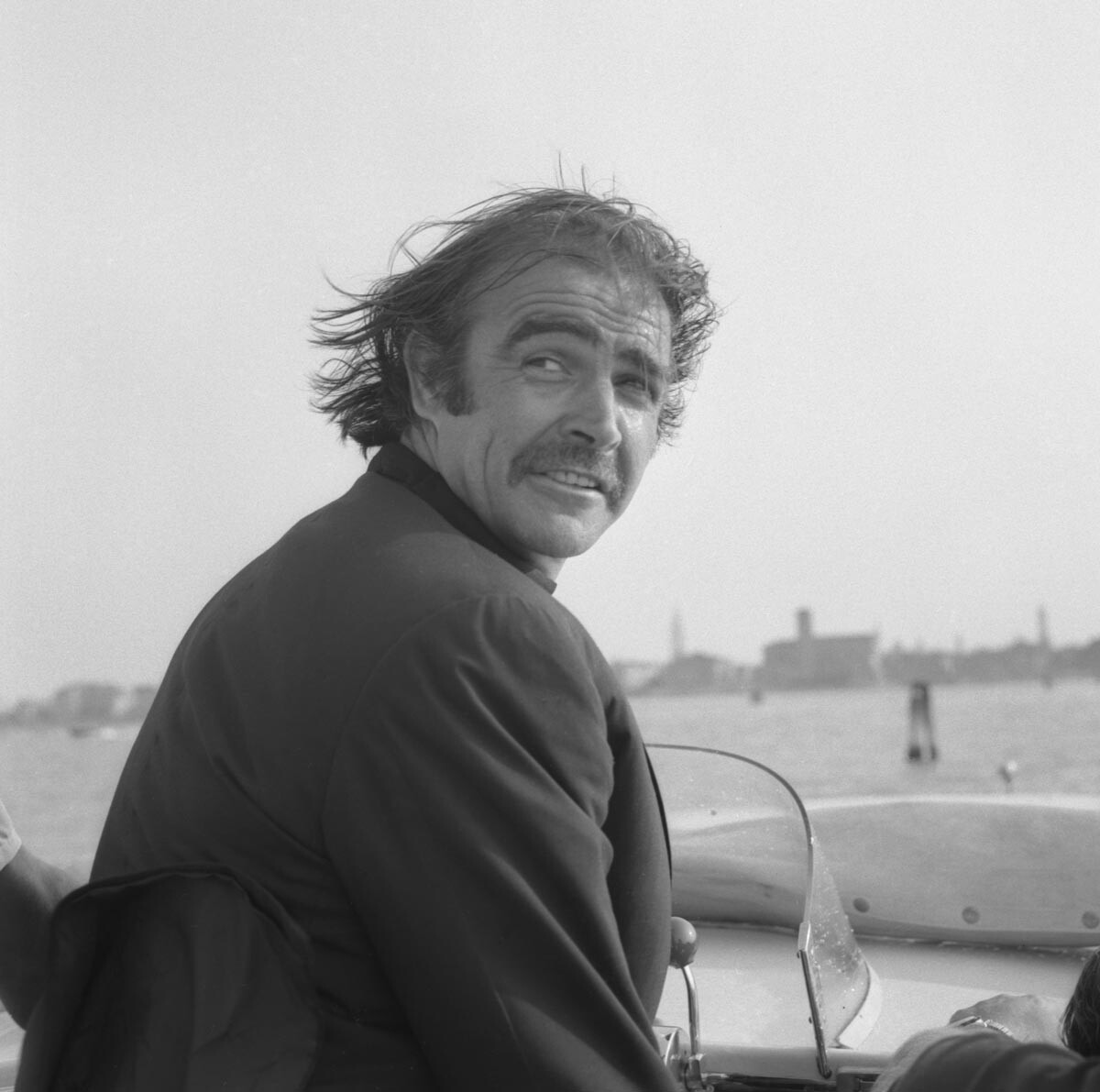

Sean Connery, portrayed on a water taxi in Venice, 1970s.

Archivio Cameraphoto Epoche/Getty ImagesA muzhik lives on his own terms. He respects society, but he can easily brush off its conventions if he considers them useless. Writer Michael Crichton, in his memoir “Travels,” described Sean Connery: “He is at ease with himself, and is direct and frank. ‘I like to eat with my fingers,’ he says, eating with his fingers in a fancy restaurant, not giving a damn. You cannot embarrass him with trivialities. Eating is what’s important. People come over for an autograph and he glowers at them. ‘I’m eating,’ he says sternly. ‘Come back later.’ They come back later, and he politely signs their menus. He doesn’t hold grudges unless he intends to.” Yes, that’s a description of a real muzhik, which Sean Connery certainly was.

Being in a tough and unfavorable situation, a real muzhik doesn’t change his mind about his actions or stray from the path he intends to follow. When Napoleon Bonaparte was summoned to command the Republican forces during the Siege of Toulon in 1793, he was an unknown young captain, and the superiors in the Republican army treated him and his plans with open contempt – but Bonaparte did his homework, he was an accomplished artillery commander, and in the end, his plan proved super effective, Toulon was taken and the royalists protecting it defeated. Napoleon was a real muzhik in the Russian sense – maybe that’s why he was respected in Russia notwithstanding the fact that he was the enemy.

People pushing a car in Valdivostok, Russia.

Vitaliy An'kov/SputnikFinally, 'muzhik' in contemporary Russian is a universal call to arms. For example, your car stalled in the middle of the road, and you need help to push it to the side. Approaching a bus stop with several guys waiting there, you don’t say something like “Господа, не могли бы вы помочь…” (“Gospoda, neh moglee by vee pomoch?” – ‘Gentlemen, could you please…’) No, you say: “Мужики, давайте толкнём!” (“Muzhiki, davayte tolknem! – ‘Muzhiks, let’s give it a push!’). Immediately, this implies at the same time that you respect all the men you’re addressing, and that you believe they’ll help you without a second’s hesitation. Because, after all, there’s a bit of real muzhik in every Russian man!

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox