Paradise Lost: Russians and the new American dream

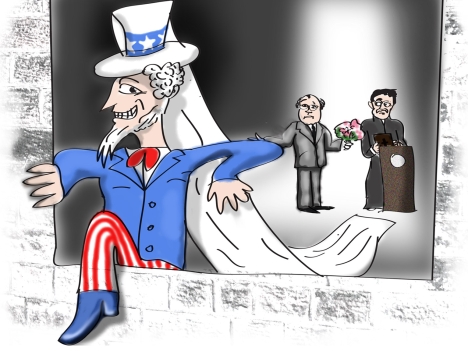

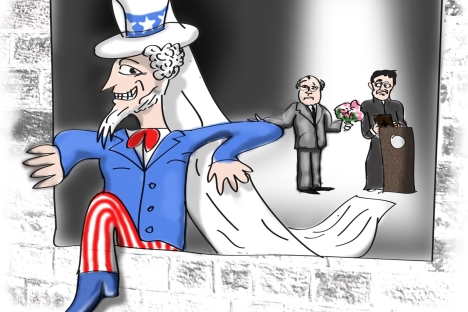

Drawing by Niyaz Karim. Click to enlarge the image.

My compatriots consider me sufficiently impartial to express grievances about America, and suitably foreign to make the case for its defense. This position puts me in a hopelessly awkward situation. By sticking up for America, I'll end up with even more egg on my face — I might as well try to defend the cosmos.

Those not wholly averse to the place find themselves having to justify the existence of everything associated with it, including hurricanes, massacre, and next-door neighbors.

Related:

America and Russia as seen from underground

What is behind anti-Americanism in Russia?

More often than not, Americans are popular in places where little is known about them. That used to be Russia, then China, the last, it seems, Albania. Nowadays everyone has discovered America, and each dislikes it in his own unique way. As in the works of old writers, Jules Verne for instance, geopolitical prejudices are tinged with national stereotypes.

The lazy anti-Americanism of the British, whose younger brother now carries the fights; the green-party and, oddly enough, pacifistic hostility of the Germans; the pompous rhetoric of the French, who thinly conceal the gastronomic undertone of their contempt (De Gaulle could never get his head round a nation able to land a man on the moon, yet make only two kinds of cheese: white and yellow).

In Latin America, Yankees are gringos; in Asia, they are rivals; Arabs see them as Jews, Iranians as devils.

But in Russia, as usual, things are different. America there is an unfulfilled dream, an unfaithful bride.

I myself grew up in America long before I settled there. If that sounds like a paradox, then it's one that runs through an entire generation. If you need convincing, take a look at the history of the question. Indeed, America never was a question, only an answer. For Brodsky, it began with Tarzan; for Dovlatov, jazz; and for everyone, books.

It wasn't the content of American literature, it was the form. We had little understanding of what the author was saying. What stirred us was the tone: the sentimental cynicism, Hemingway's "irony and pity" in such virtuosic proportion that it became for us a school of feelings and, at the same time, an injection of freedom.

A stalwart against authoritarian interference, America was our own private space. Back then, the Seventh Continent was not a Russian supermarket, but a soul — discovered all at once, from Brodsky to Solzhenitsyn. "Communism," said the latter in the argot of the time, "must be built not of brick but of people."

"God forbid," we would answer him now.

Let's keep the stones and the people separate. It was America that taught us to do that, to partition realms. And in order to love it, we did not need Americans in the flesh. On the contrary, they only spoiled matters. The first U.S. citizen I ever saw, quite literally in the flesh, was in the communal shower of the Repino student hostel, which we were sharing with a trade union delegation from Detroit.

Despite the presence of foreign guests, the water was cold and the American blue. A spare smile crossed our lips, but we did not exchange a word. My knowledge of English extended to describing my summer vacation down on the collective farm, and besides, his teeth were chattering.

Between love and indifference, a new hatred has emerged. "America," a writer once explained to me, "is not to blame. Like a microbe, it infests what it can."

I know this to be untrue, because Americans are not cut out for imperialism; unlike us, they do not gaze longingly abroad, preferring the comfort of home. Isolationism is not just a dream, but the very essence of America. Not for nothing was it dubbed the "New World," for it strove to break its ties with the Old.

The trouble is, I have never managed to convince anyone of this. Everyone has his or her own opinion about America. The myth refuses to die, and can only be replaced or erased from the mind. Unable to do the former, we have stopped short of the latter.

Hatred of America is incurable. The only option is to forget about it, and that is made easier by the fact that we—Russians and Americans--are unwittingly becoming ever more alike. Goodbye communal apartments, welcome unemployment. In Russia, many people have gotten themselves a home, a garden, a private doctor, an accountant, and, of course, the ubiquitous lawyer. Movies are one size fits all, not to mention idols.

"Residents of the village Oktyabrskoe," reads a newspaper article, "want to rename their rural homeland 'Michael Jackson'."

In the course of this inevitable convergence, one side is infected by the other's profound, sincere, not arrogant but naive indifference to the outside world, which, it has to be said, is of no concern to either Russians or Americans. But before America is forgiven, Russia must, like first love and lost youth, let it go.

Alexander Genis is a Russian-American writer, broadcaster and columnist for the Russian newspaper, Izvestia.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox