How the ancient Russian bagel became a culinary symbol

Kolomna kalach.

Ilya Pitalev/SputnikIn old times, there were no burgers and french fries in Russia, but there was plenty of ancient “fast” food. All the fairs, markets and bakeries across the country offered many kinds of pastry, but the most beloved was a simple bread called kalach (literally “a circle”), that looked like a bagel with a “handle”.

This “handle” was supposed to be thrown out from a hygiene point of view (there’s even a saying, “to reach the handle” that means extreme degree of despair when you have to eat the handle of kalach).

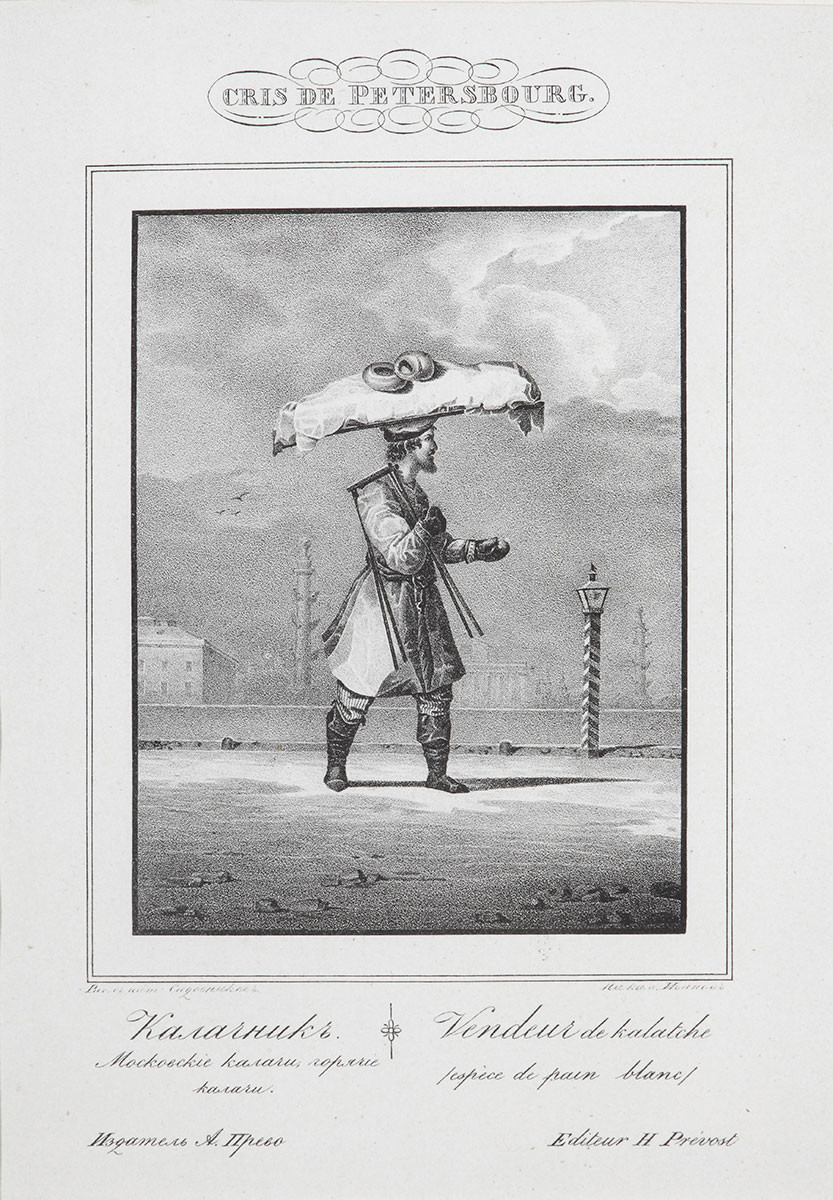

The Bread Pedlar, 1830-1831. Found in the Collection of State Museum of the History of Saint Petersburg.

Getty ImagesThey’ve been known since at least the 14th century and were very popular, not only among peasants, but also with nobles and even tsars. Only flour, salt, water and a sourdough are needed: this pastry has no egg or butter. Since the tsarist times, Russian regions have concocted their own recipes for kalachs and some still exist today.

Moscow kalach

Culinary historians are still arguing about where the kalach appeared first. But the main kalach “promoter” is considered to be a Moscow baker named Ivan Filippov. Since the mid-19th century, his family owned the largest chain of bakeries in key Russian cities. He successfully sold his rolls to St. Petersburg, Siberia and even Paris. Before the transportation, they were frozen and then “thawed” when needed with hot towels: they actually kept their freshness for a long time.

For the Moscow kalach, bakeries used only wheat flour of the highest grade and, therefore, they turned out to be very lush and soft.

Today, some modern Moscow cafes suggest variations of old-style pastry with new ingredients: semolina, malt and spices.

Kolomna kalach

At the Kalachnya museum in Kolomna.

Ilya Pitalev/SputnikEating a kalach in Kolomna, a small town near Moscow, is a “must have” for any tourist.

The dough for Kolomna rolls was considered the most intricate in Russia. It was kneaded from different types of flour and spices to make it porous. For the tsar’s table, Kolomna bakers added berry syrups, raisins, mint, cinnamon to the dough - in short, everything most expensive that was available at that time.

Kalach baked at the museum in Kolomna.

Getty ImagesThere is a big museum dedicated to the local kalach, where visitors can not only look at the ancient baking process, but also try to make it themselves. Those who do not want to wait can grab some kalachs from a wooden stove in the nearest kiosk.

Murom kalach

The monument to kalach in Murom.

Legion MediaThe coat of arms of this old Rus’ city in Vladimir Region depicts three golden kalachs.

Murom is the homeland of “rubbed” kalachs. The dough for such a pastry is rubbed and mixed for a long time, which makes kalach airly. Even today, Russians call an experienced person “terty kalach” (“rubbed bagel”).

Ancient kalach is still baked in the city by the bread factory and the Holy Transfiguration monastery. One of the most popular souvenirs from there is the huge kalach with seeds, however many locals say that modern kalach is sweeter than it was in the times of their childhood.

Siberian kalach

This is how Tobolsk kalachs look like.

Vasily PalshinIn the city of Tobolsk, you can find yet another kind of kalach. “Firstly, they are baked from three types of flour: wheat, semola (whole grain) and rye. Secondly, they are stuffed with different fillings,” says a baker from the ‘Mark and Lev’ restaurant. It can be chicken, duck or apples with nuts. A yummy reason to visit Tobolsk!

Kalachs from Omsk are similar to Moscow pastry in taste, but look like a round bagel in shape, but without a “handle”.

Saratov kalach

The pastry in Saratov (Volga Region) looks very different: more like a cake or high bread. In the old days, they were baked only from the local type of very expensive wheat called “beloturka”. Saratov used to bear the name of the bread capital of Russia and the quality of the local flour was very high.

The modern recipe (since the 19th century) has changed a bit: bakers mix the flour of soft and durum wheat.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox