What happens when permafrost melts?

Russia has more than enough permafrost: two-thirds of the country, from Taimyr to Chukotka, is frozen ground. Life in those areas is not easy: winters are cold, not much grows on that land, and any construction is very expensive. Yet, despite all this, local residents are doing their utmost to preserve the permafrost, while permafrost scientists are closely monitoring any climate changes that could affect those areas.

Nothing is permanent, not even in nature

Strictly speaking, the term ‘permafrost’ is not very accurate from a scientific point of view. The Russian term “permanent frost” originated in the 1920s, but already in the 1950s, scientists decided that there was nothing permanent in nature and began to refer to it as “perennial frost”, explains Nikita Tananaev, a hydrologist at the Permafrost Institute in Yakutsk. “Their definition of it was simple: ground that remains frozen for two or more years.” In fact, its upper layer melts a little in the summer, creating very interesting landscapes.

The following photos were taken near the village of Syrdakh in Yakutia. The “summer” permafrost earth looks like melted chocolate that flows directly into a lake.

This phenomenon is pretty common for Yakutia. In summer, temperatures here rise to above 30C and permafrost thaws two to three meters deep. In winter, it will freeze again.

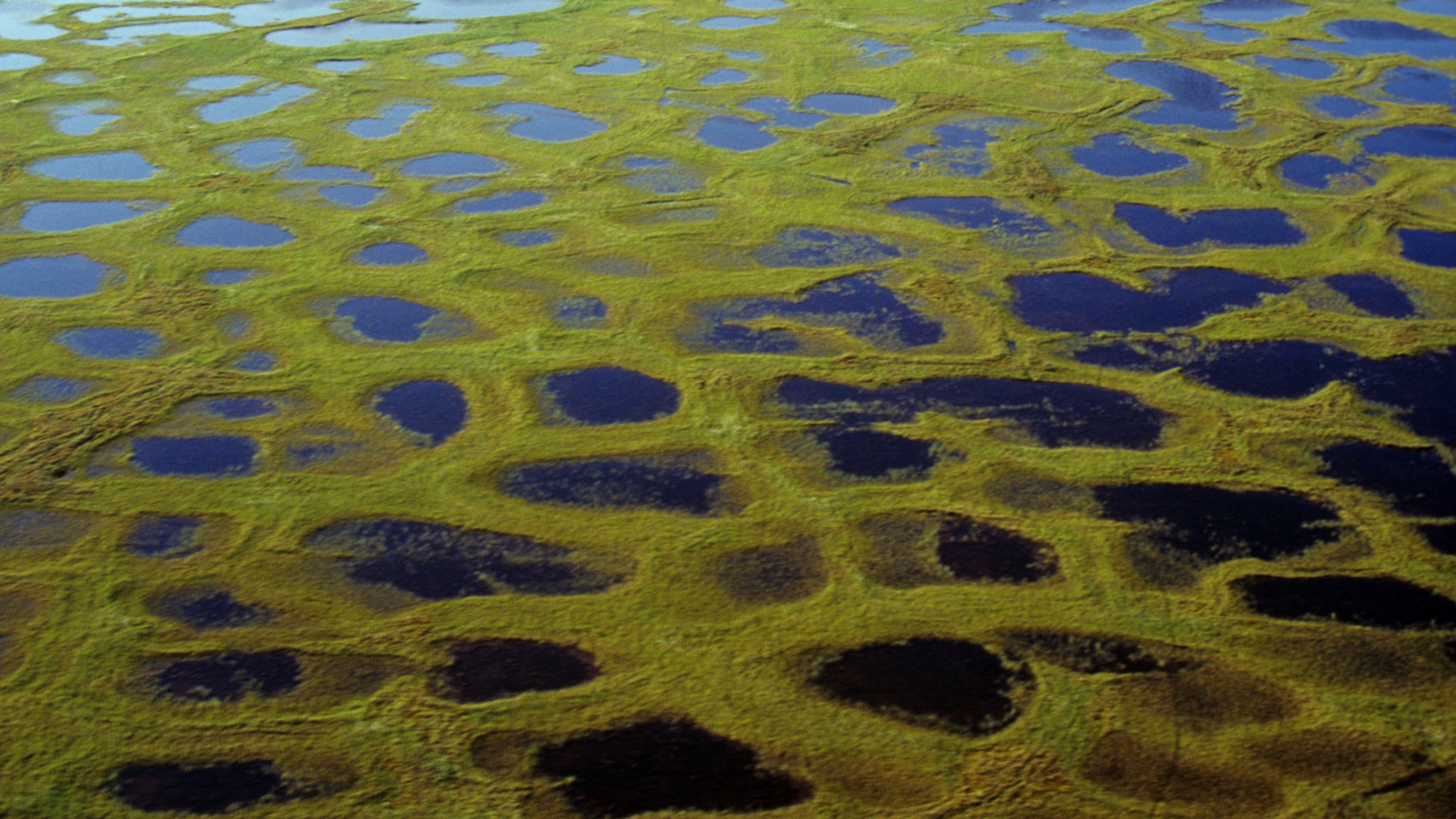

There are areas where there is clear ice underground, says Tananaev. “From above, they resemble a giant net. For thousands of years, the soil would freeze, shrink in volume and crack, and in summer, it would fill with water, gradually sprouting narrow ice streaks tens of meters deep into the ground. This is how the polygonal tundra is formed.” These polygons are quite small, under 40 square meters. There are hundreds of them in Yakutia, Taimyr, and Chukotka.

Clear ice is not just restricted to polygons. There is also stratified ice, i.e. not streaks of ice, but literal solid walls of ice along river banks.

Even more spectacular is the summer ice on the ground’s surface: the most famous of these glaciers is called ‘Buluus’ and is located 100 km from Yakutsk. Just imagine: the temperature is 30C above zero, the sun is bright - and you are surrounded by ice.

This natural phenomenon is most common in the mountains, where underground waters, rising to the surface along the cracks, in winter form aufeis (a sheet-like mass of layered ice that forms from successive flows of ground water during freezing temperatures; in Russian, nalyed) on rivers, which practically do not melt.

Bolshaya Momskaya icing.

Roman Denisov/SputnikThe biggest one is the Bolshaya Momskaya nalyed in Yakutia. It is an ice field 26 km in length alone! Ice in it can be up to 5-6 meters thick, with water flowing on its surface and forming small channels through it. The water turns the ice bright blue in color. In summer, it melts a little, but the following winter new ice is formed. Yakutia has an enormous number of nalyeds like this: each winter, more than 50 cubic kilometers of water freezes in them.

Incidentally, river ice is used as a source of freshwater here, since digging wells in permafrost is a dubious undertaking, to put it mildly.

There was, however, one enthusiast who decided to try and dig a well in permafrost. In the early 19th century, the head of the Russian-American Company, merchant Fyodor Shergin, decided to look for water under a layer of frozen soil. In the end, he had to stop at 116 meters - they never reached the water, and the Shergin mine began to be used for scientific purposes. In the 1930s, the mine was drilled to a depth of 140 meters and handed over to the Permafrost Institute. These days, with the use of special sensors, the mine is used to study temperature changes at different depths of permafrost.

The Permafrost Institute in Yakutsk.

Valery Shustov/SputnikA natural freezer

Local residents have long learned how to adapt the cold to their needs. In Yakutia, for example , people dig cellars underneath their houses and store food in them all year round, since the temperature there is always below zero. That said, digging out a cellar here takes a little more time than it would further south, because in addition to a shovel, it requires... fire! That is, first you have to make a bonfire to thaw the soil, and only then can you start digging.

The village of Novy Port in Yamal is the home to the world's biggest natural “freezer”. In the 1950s, some 200 caves were dug out and connected by passageways. They were used for storing fish. The temperature there is naturally maintained at about 12-15 degrees below zero all year round.

The natural "freezer" in Novy Port.

portadm.ru/SputnikIncidentally, in every region, permafrost has its own smell. “If you walk into the underground tunnel of the Permafrost Institute in Yakutsk, you will feel a very strong smell of organic matter that was in the soil and now has begun to thaw and decompose,” Tananaev says. “Whereas in the tunnel of the Permafrost Museum in Igarka in Krasnoyarsk Territory there is no particular smell. It just smells of damp earth because the soil there is completely different.”

What would happen if the permafrost thawed completely?

Scientists have noticed that in recent years, in many parts of the world, permafrost has been thawing to a greater depth than before. “So far, we are not losing a lot of permafrost per year - about 10 centimeters over 20 years (and not everywhere, only in some areas of Norilsk or in the south of Transbaikal Territory), whereas in Yakutia, permafrost goes for hundreds of meters, even up to one and a half kilometers, deep,” says Tananaev. But what consequences could the thawing of permafrost have?

Yakutsk in winter.

Bolot Bochkarev/Sputnik“Take a pack of green peas, put in a freezer, and it will lie there and look good, be it in 10 or in 1,000 years' time, - Tananaev explains. – Permafrost is that freezer, except that instead of green peas there is grass, leaves and peat. All this organic matter thaws and is decomposed by microorganisms, which emit methane and - under the influence of other processes - also CO2, the two main greenhouse gases.”

“The more permafrost thaws, the higher the temperature and the more permafrost thaws. It is a vicious circle,” he adds. As a result, he claims, the average annual temperature is gradually rising.

Tananaev remembers a winter in Yakutsk 10 years ago when for a whole week the temperature was 60C below zero. Whereas in recent years, winter temperatures have been just minus 35-45C. One of the reasons is urbanization: although all buildings in the northern cities are built on stilts, thermal radiation from apartment blocks heats the air anyway. The soil also thaws from any leaks of hot water: as a result, buildings sag and you can see cracks on their facades, especially along window openings. In the end, the building loses its insulation (which is no joking matter in the north), while its foundation loses its bearing capability. “In Norilsk, almost a whole street was demolished because of those leaks,” Tananaev recalls.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox