The Russian rover that made it to Venus

By the late 1950s, the Soviet space program was experiencing an unprecedented boom. At the time, successful landmark missions took place practically every year: the first artificial satellite, the first living creatures in space, the first Moon flyby and pictures of its dark side. After those triumphs, it seemed anything was possible. That is why when the issue of carrying out the first ever landing on another planet was raised, Soviet scientists and engineers responded with enthusiasm.

Today it sounds utopian. At the time, precious little was known about other planets to carry out such difficult missions. However, in August 1959, a meeting was convened, and on December 10, a government decree issued on setting up stations for a mission to Venus (and Mars too). By the end of 1960, those stations, which did not even exist yet, were supposed to fly into space!

Missions in the dark

The first mission would be to Venus as the planet is closest to Earth, the team decided. By that time, the Soviets had the R-7 rocket, Sergei Korolev's brainchild, which had already launched artificial satellites and would subsequently take people into space. For a deep space mission, it needed to undergo a major upgrade with a completely new stage with unique characteristics. Fortunately the rocket’s design allowed for this.

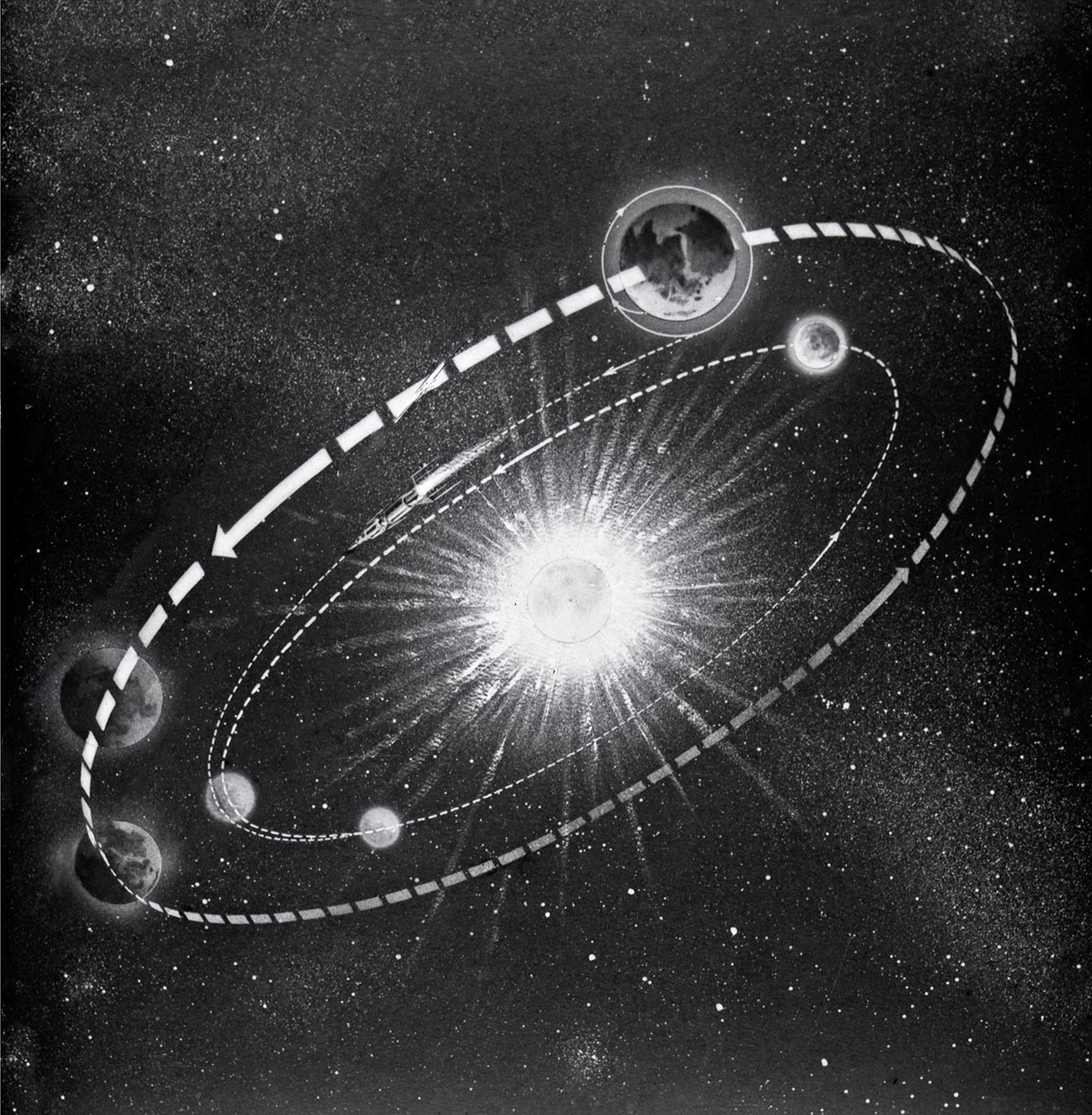

Flight diagram of the spacecraft "Venera-1" to Venus.

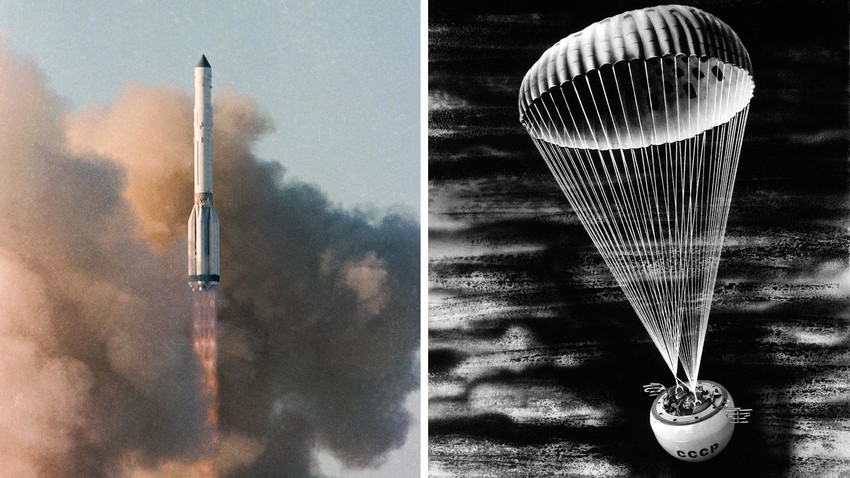

SputnikA testing scheme was chosen - as in the case of the Moon flyby (which took place in 1959), the plan was to drop a probe directly onto the surface of the planet, by parachute. Predictably, the first landing mission was doomed to fail.

The fact is that at the time Soviet scientists seriously believed that Venus had an atmosphere similar to Earth's as well as water and extraterrestrial life (in fairness, they were not alone in this - American scientists at the time believed it could harbour life too). That is why the Venera 1 mission was supposed to directly impact the surface of Venus. However, it missed. Communication with the probe was lost meaning it could not correct its course; instead it flew 100,000km (62,000 miles) past the planet in 1961: at a cosmic scale, it was not such a massive miss as no-one had ever been so close to Venus before.

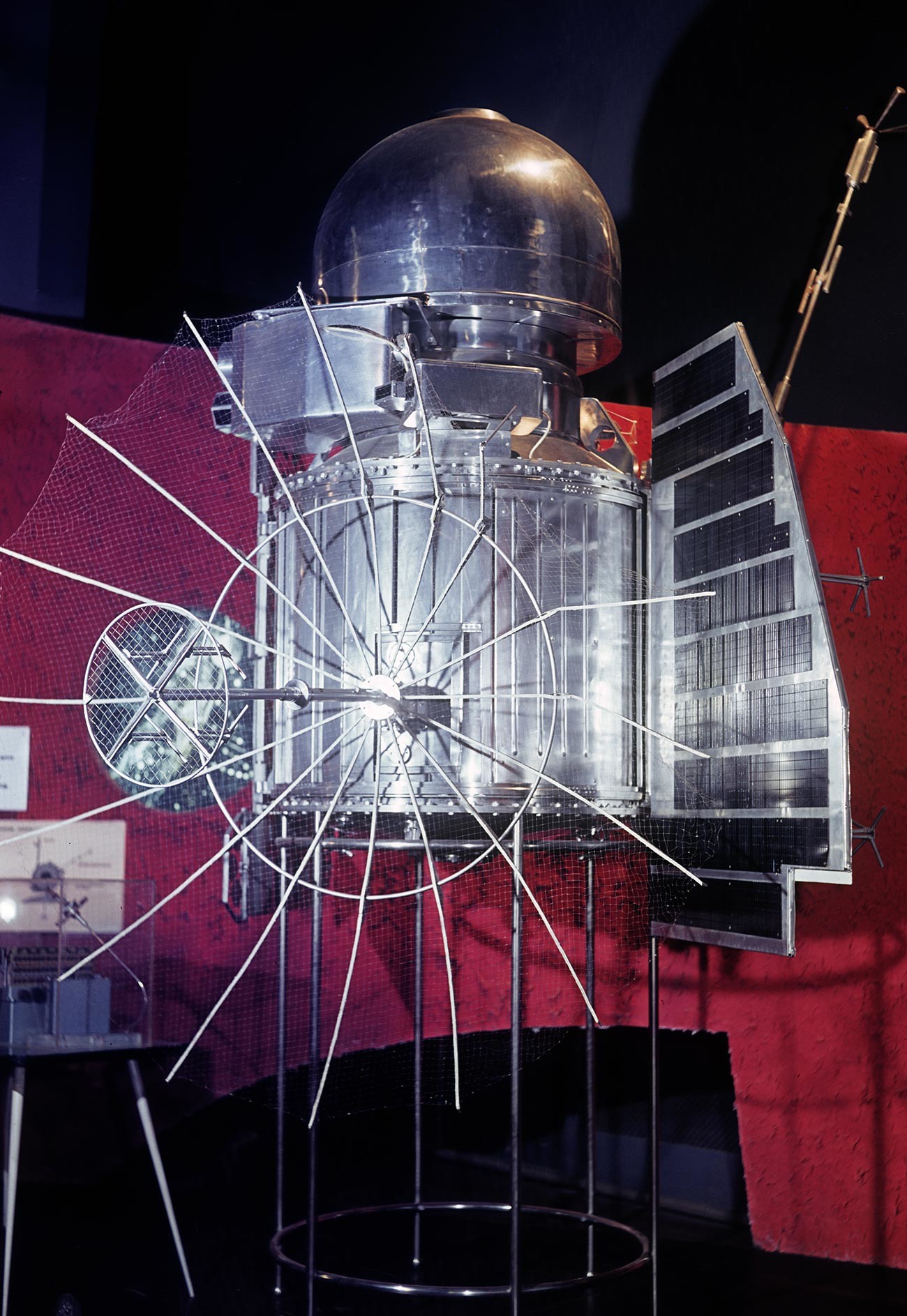

Model of the station "Venera-1"

Alexander Mokletsov/SputnikWhat followed was a decade-long series of ill-fated failed missions to "conquer" Venus. During almost every launch window, a new Soviet research station was launched to Venus. However, in the absence of even an approximate idea of the real state of affairs on the planet, the probes did not have the slightest chance of reaching its surface.

Venera 4, Venera 5 and Venera 6 were torn apart by atmospheric pressures. On the plus side, data transmitted by the probes back to earth provided accurate information about the composition of the atmosphere, its temperature and pressure. For example, it turned out that the atmosphere of Venus was 90 percent carbon dioxide and had “sky-high” pressure and temperature. In other words, finding life on Venus was out of the question.

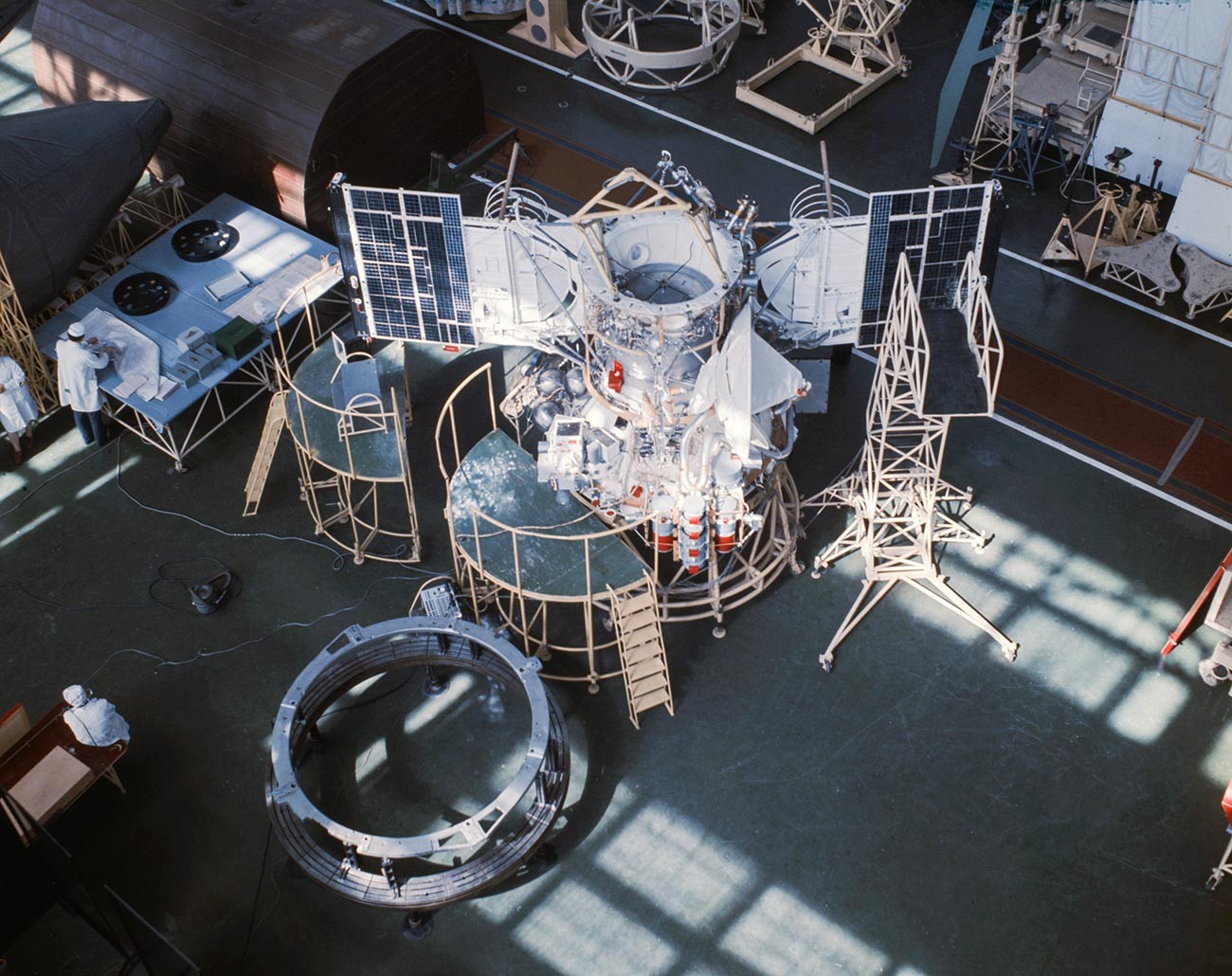

Researchers preparing for the test.

Sputnik“I witnessed how disappointed the scientists were when they did not find life on Venus. Two of them even said that their lives had been in vain as it was only this dream that had brought them into science in the first place... By the way, one of them later became a clergyman,” space journalist Vladimir Gubarev recalled in his book.

From that moment on, the Venera space program changed its focus: now the task was to find out whether there had ever been life on Venus.

"That Venera 7 landed on the surface is a miracle"

Success finally came during the Venera 7 mission, which in fact was Venera 17 but the Soviet Union preferred not to make its failures public.

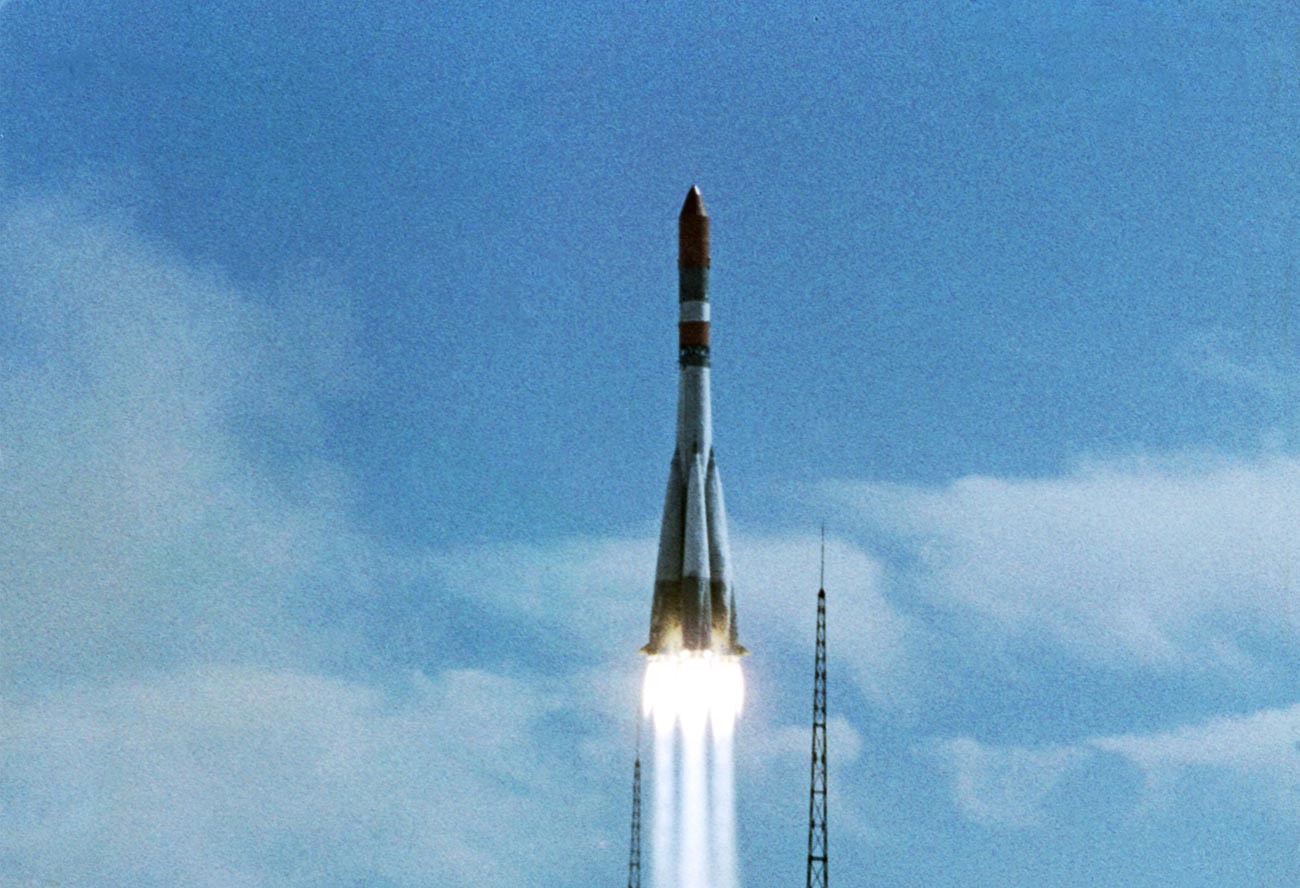

Rocket launch with the "Venera-7" station.

TASSAfter a long scientific debate, having taken into account all the new inputs, the engineers decided to play it safe and develop a new lander capable of withstanding pressure of 180 atmospheres and temperature of 540C (1,004 Fahrenheit) for 90 minutes. Its body was made not of an aluminum-magnesium alloy, as in the previous Venera probes, but of titanium, which increased its strength and weight. The new rover weighed half a tonne.

"Venus-7"

Vitaly Sozinov/TASSAs a result, the number of scientific instruments it could carry was reduced. In effect, its capabilities were modest: it could measure temperature and pressure on the surface, analyze the type of the surface and measure maximum acceleration via its braking section. Its pennants carried Lenin’s image and the Soviet flag with its familiar hammer and sickle emblem. And that was it.

Venera 7 was launched from the Baikonur cosmodrome on August 17, 1970. As a backup, five days later, an identical spacecraft was launched. However, it failed to reach Venus as an engine explosion prevented it from leaving Earth's orbit. Thankfully, the "original" spacecraft reached the vicinity of Venus 120 days later and on December 15 made the first ever soft landing on another planet; the famous American moon landing of July 1969 was, of course, on an orbiting body, not another planet.

Indeed, it looked like a miracle. Throughout the mission, the chances that something could go wrong were overwhelming.

In the end, Venera 7 nearly suffered the fate of its predecessors: having already reached the “target” and entered its atmosphere, its parachute exploded and the probe descended faster than it should have. For a while, it was thought that after such a landing, the probe would not function, because when entering the atmosphere its telemetry switch failed, meaning that the only data transmitted back to Earth during the descent and after landing was the atmospheric temperature. Fortunately, subsequent analysis showed that for 23 minutes after landin the probe had been transmitting data directly from the surface of the planet.

Forgotten planet

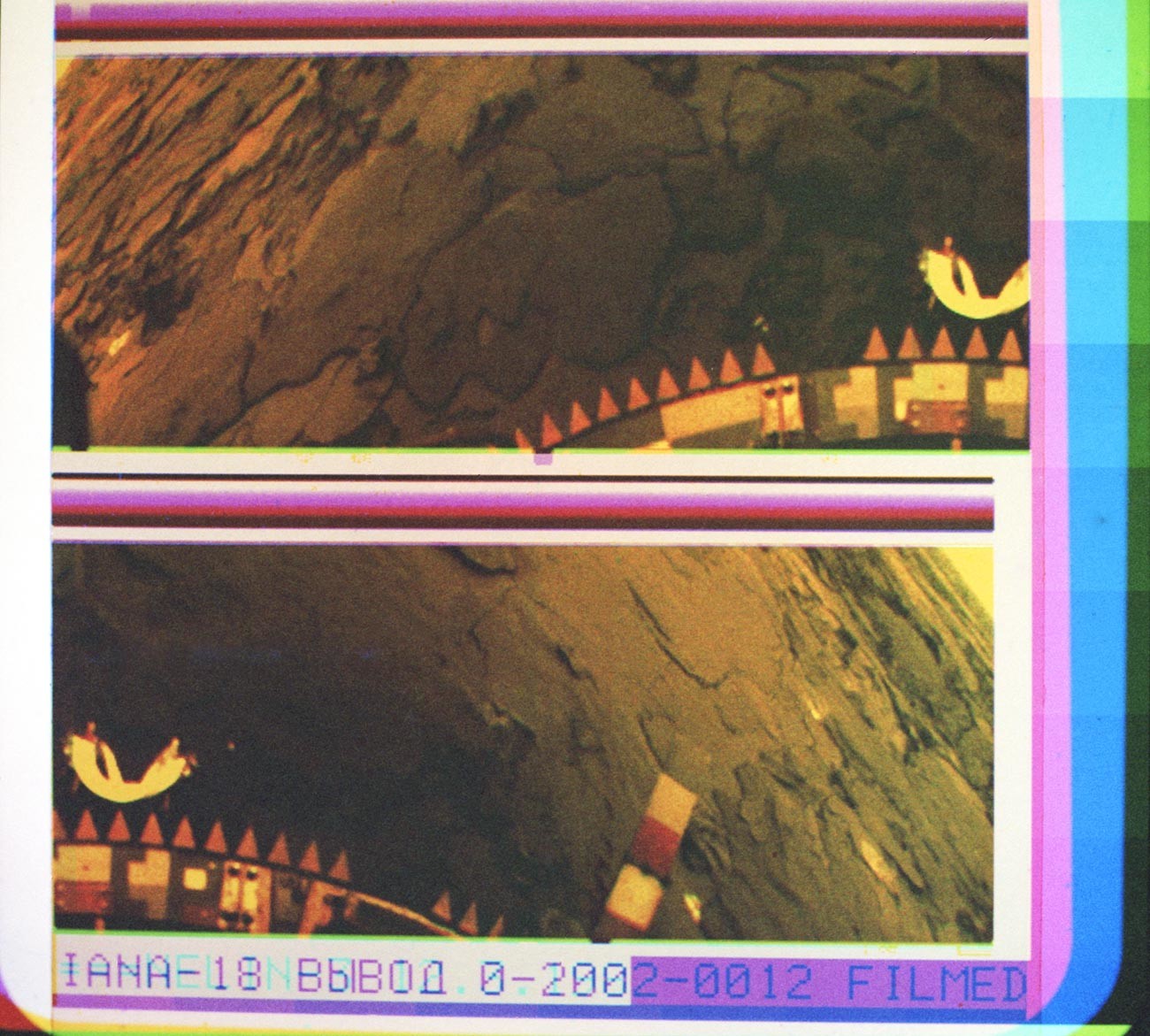

After Venera 7, a new generation of spacecraft were flown to the planet, which allowed the USSR to secure leadership in the exploration of Venus and become the first country to get the first image from its surface. The photo was taken less than six months later, by Venera 8. Those were, among other things, the first ever photographs from the surface of another planet.

Color panoramic image of the surface of Venus.

In total, the Soviet Union launched 27 spacecraft to Venus. The last was Venera 16, after which a new space program, Vega, was launched. In 1984-1986, with the use of a balloon explorer, it successfully studied the Venusian atmosphere and obtained the most accurate to-date data about the planet.

But still this is very little. We know little about all the substances that make up its cloud layer or how they are formed. These data could be collected by a full-fledged interplanetary station in the atmosphere of Venus - but it would cost a fortune. That is why for many years, Venus was practically forgotten by researchers.

Launch of the space mission "Vega-2"

Albert Pushkarev/TASSIt made a bit of comeback in October 2020 - because of phosphine, a gas compound that, according to the latest research, may indicate the presence of life. Phosphine is present in the Venusian atmosphere, in its cloud layer, which has revived interest in the planet. Roscosmos is planning a mission to Venus for 2029, but there is a chance that it could take place earlier, in 2027.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox