Why Russia sent a new module to the ISS

Nauka is larger than Crew Dragon - and it’s a new part of the ISS

‘Nauka’ (“science” in Russian) is the country’s first module aboard the International Space Station (ISS) in 11 years, as well as the first private Russian laboratory in space. However, it’s slightly more than that: The module is practically a large spacecraft, which, after entering orbit, can travel to the ISS on its own and dock with it. No American or European modules exist that can do that. NASA modules, for example, can’t fly on their own, being more akin to buildings; they are delivered to orbit in cargo holds aboard shuttles and dock to the ISS using an additional module.

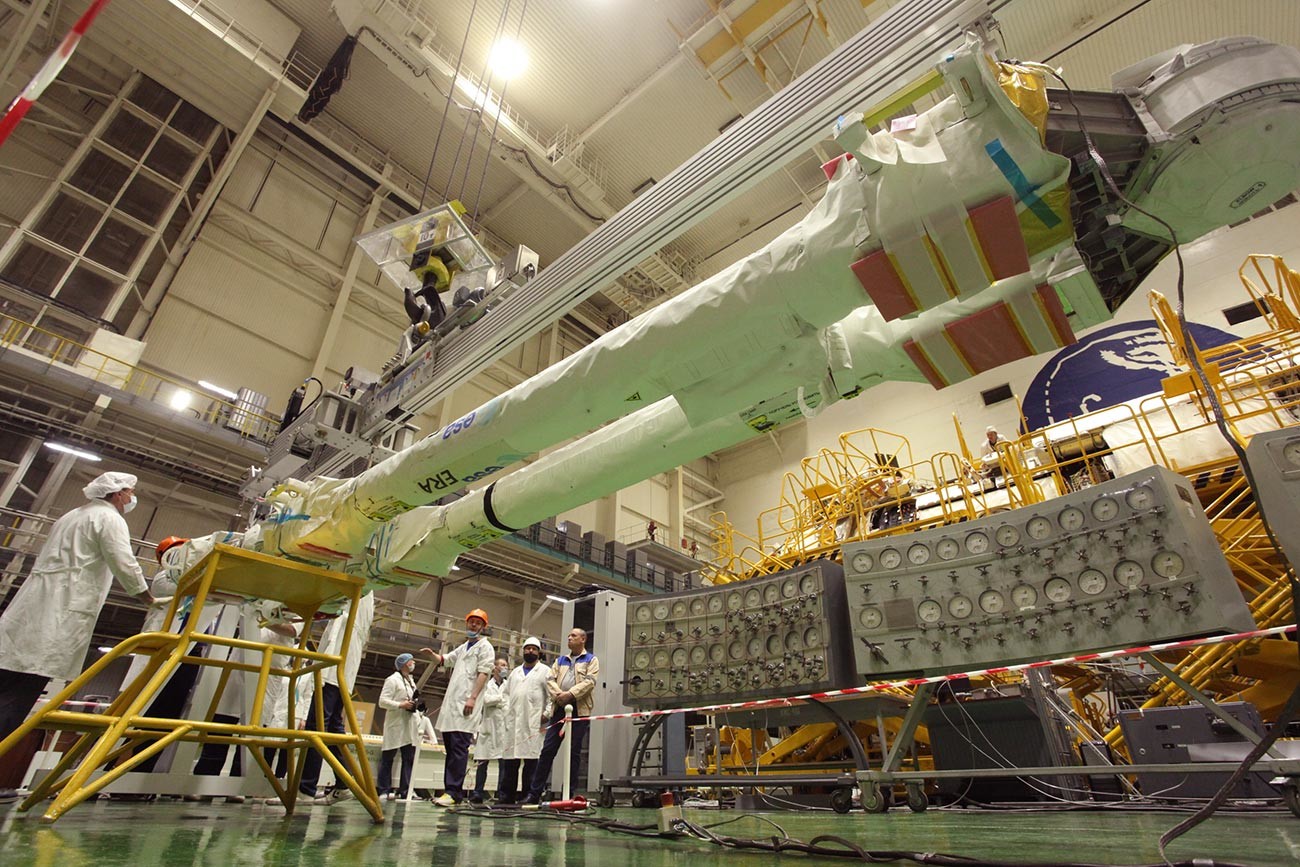

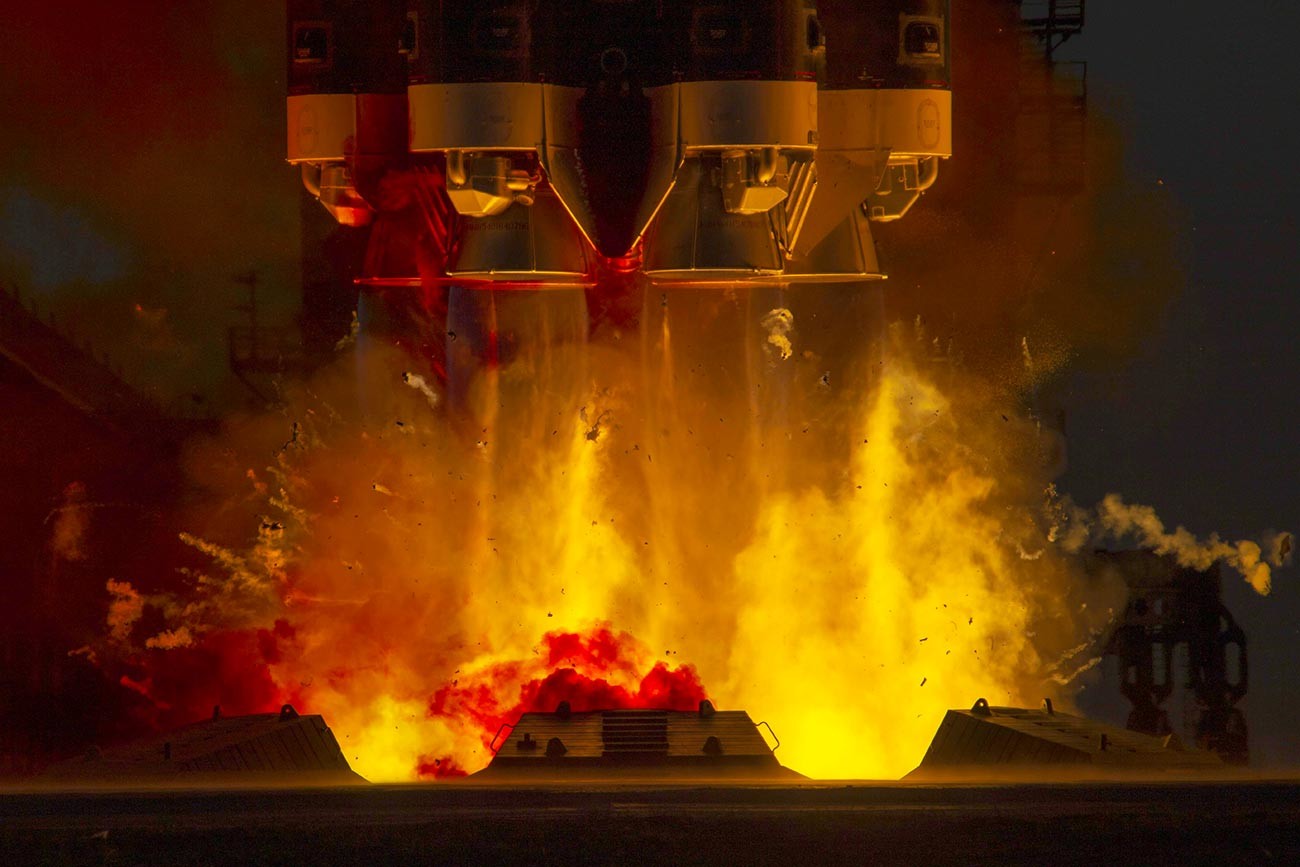

‘Nauka’ weighs more than 21 tons and measures 13 meters in length and 4,2 meters in diameter, making it the heaviest Russian module ever built. It launched on July 21 from the ‘Baikonur’ cosmodrome and is supposed to take eight days to reach the ISS, which means we should hear from it on July 29.

Scientific experiments with growing embryos

Nauka’s first intended use is science. Today, the Russian segment of the ISS has two large modules - ‘Zarya’ and ‘Zvezda’ - and three smaller ones, also used as docks for space ships.

Installation of the European ERA manipulator

Space Center "Yuzhny" / RoskosmosThe ‘Zarya’ (“Dawn”) is used mostly as a cargo hold. ‘Zvezda’ (“Star”) is the main module of the Russian segment aboard the space station. It only houses two cabins, life support and navigation systems. There’s no scientific section: equipment has to be placed in an available patch of space to be used, then stored away again, which isn’t ideal.

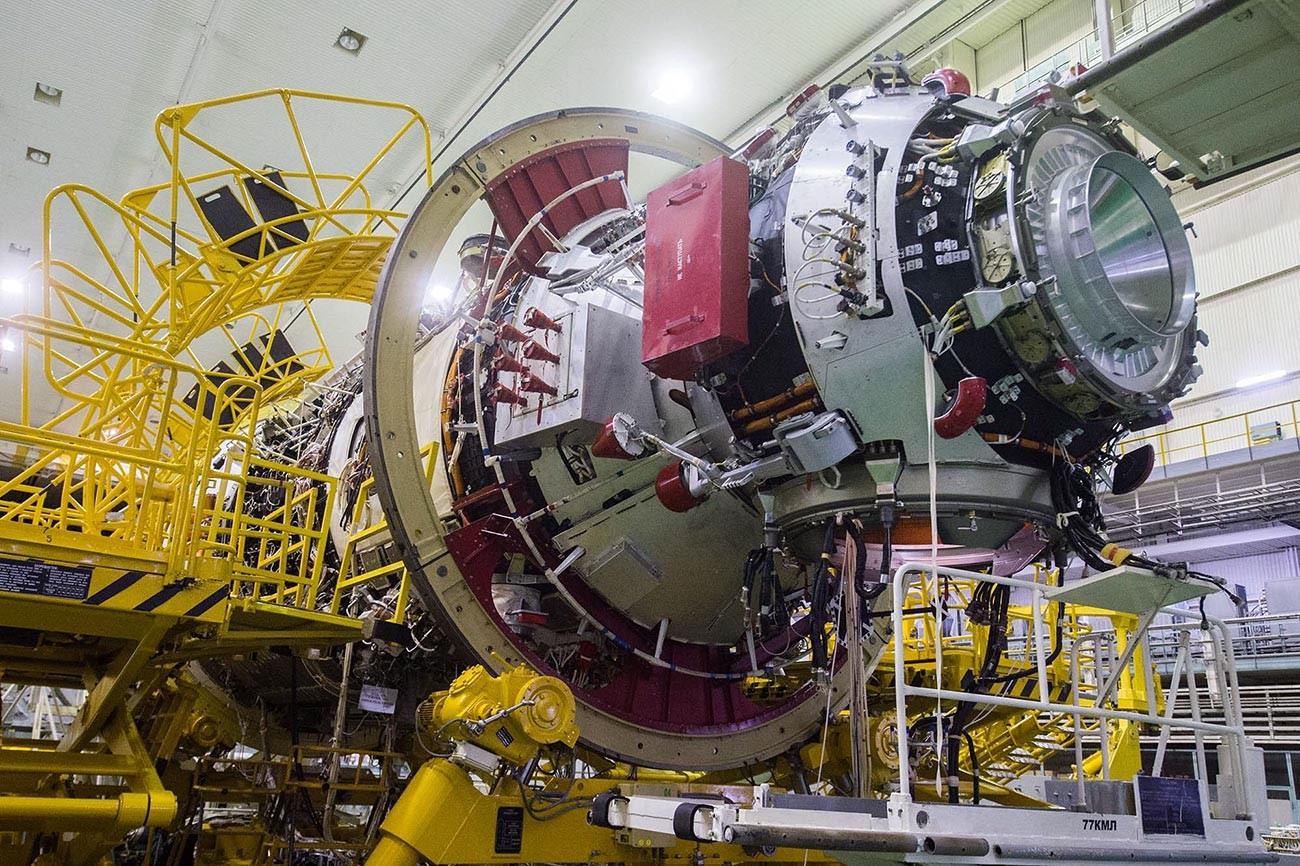

‘Nauka’, on the other hand, has more than enough space for science. There are 14 workspaces inside the module and 16 outside, as well as a separate lab. Among other things, there’s a centrifuge, which can create artificial gravity and allow for studying its varying degrees on the development of embryos.

Another bit of innovation aboard the ‘Nauka’ is the European ERA manipulator outside: The remote-controlled space hand will allow scientists to easily make repairs and upgrades on the outside of the station without venturing out too often, which sets the Russian module apart from other countries’ ones.

‘Nauka’ can be considered innovative from the Russian, as well as the international standpoint, when compared to the three other ISS modules: the American ‘Destiny’, Europe’s ‘Columbus’ and Japan’s ‘Kibo’. But there are nuances. The work surfaces are geared towards work with scientific equipment designed specifically for them. Other labs, for the most part, allow for using various non-native equipment.

Why they couldn’t launch ‘Nauka’ for 14 arduous years

‘Nauka’ turned out to be one of the most problematic projects for the Russian segment of the ISS - it really took its time. Work began back in the mid-2000s and it wasn’t all from scratch: The idea was to attach a reserve ‘Zarya’ module to it (it was the first to be launched, although, despite being Russian, the financing came from NASA).

The ‘Zarya’ double was 80 percent ready when it was decided to transform it into a space lab, to be launched in 2007. However, deadlines were moved many times, due to technical and financial issues.

The biggest headache was in 2013: During testing, small metal debris was discovered in the fuel tubes, measuring only 100 microns. The same faulty construction was later discovered in the fuel tanks. It was impossible to get rid of. “Cleanup work was done double time. It continued seven days a week, spread across two shifts, constant panels and meetings and attempts at cleaning and repeat testing. We received results that the receptacle was clean, then dirty again,” sources at the Khrunichev Center said.

This small debris could’ve left ‘Nauka’ stranded on Earth forever: foreign objects in fuel tubes and tanks can theoretically enter the engine section and stall it - the module would simply have gotten stuck in orbit, then burned up falling back into the Earth’s atmosphere. Developing new tanks and tubes was out of the question. The factory that built them was long gone and no other factories with the ability to build them to the same specifications existed in Russia anymore. And by the way - ‘Nauka’s reserve tanks suffered the same problem.

Finally, after numerous attempts at cleaning the tanks, the panel cleared them for use, but only on the condition that they’d be used once, for entering orbit, and not be integrated into the complex fuel system of the ISS (which would endanger the entire space station).

‘Nauka’ will prolong the life of the ISS - but not for long

The ISS use-by date of 2024 is approaching fast and member countries are considering their options. In 2020, Vladimir Solovyev, the deputy director at leading constructor, RKK ‘Energiya’, said: “Even now, there are a number of elements that have seriously been affected by wear and tear and are no longer fit for use. Many of them can’t be replaced. After 2025, we predict cascading errors and breakages across the board.”

Read more:What’s Russia going to do with the ISS?

The options are as follows: to simply drown the ISS in the Pacific Ocean, or repurpose it as a hub between the Earth and the Moon, which is still being considered by some member countries. As for Russia, it is in favor of prolonging the station’s life to 2028 and maybe even 2030, which is when it plans to exit the ISS project regardless and create its own space station - the ‘ROSS’. The decision to use the ‘Nauka’ seems to have been inspired by the need to extend the Russian stay.

When it’s all over, ‘Nauka’ won’t actually be joining ‘ROSS’. “It is already so tied to the ISS, it would simply be too difficult to adapt it for use with a new station,” Solovyev said in April, 2021.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox