Church of John the Baptist at Tolchkovo: Crowning Glory of Yaroslavl

Yaroslavl. Church of Decapitation of John the Baptist at Tolchkovo, apse & north chapel. Northeast view. Aug. 15, 2017.

William BrumfieldAt the beginning of the 20th century, the Russian chemist and photographer Sergei Prokudin-Gorsky devised a complex process for vivid, detailed color photography (see box text below). His vision of photography as a form of education and enlightenment was demonstrated with special clarity through his photographs of architectural monuments in the historic sites throughout the Russian heartland. Logistical support for

Church of Decapitation of John the Baptist, with bell tower. East view. Left: factory fence. June 29, 1995.

William BrumfieldOne of Russia’s richest historic sites

Commercial center

Founded in the early 11th century by Yaroslav the Wise — one of the greatest rulers of medieval Rus — by the early 13th century, the city already had masonry churches within monasteries, unusual in a time when most buildings were of logs. In 1238, Yaroslavl was sacked by the Mongols during their conquest of central Russia. Although recovery from Mongol dominance was slow, union with Muscovy in the 15thcentury integrated the town into a larger political and economic structure.

Church of Decapitation of John the Baptist, with bell tower. West view. Right: Ascension Church (not extant). Summer 1910.

Sergei Prokudin-GorskyYaroslavl benefited from its location, which enabled it to serve as a center not only for trade within the extensive Volga River

Church of Decapitation of John the Baptist. West view. July 24, 1997.

William BrumfieldCommerce in Yaroslavl declined during the interregnum following the death of Boris Godunov in 1605. Known as the Time of Troubles, during this period, much of the country was devastated by political and social chaos. Yaroslavl eluded the worst of the cataclysm, and in 1612 the city served as a center for national forces against a Polish occupying force in Moscow.

The participation of Yaroslavl's leading merchants in this campaign brought them extensive trading privileges from the government of the new ruler, Mikhail Fyodorovich (1596-1645), first tsar of the Romanov dynasty. As a result, during the 17th century, the city not only accumulated the wealth necessary to build elaborately decorated churches but also established connections with cultural centers to the west.

Church of Decapitation of John the Baptist. Northeast view. Aug. 15, 2017.

William BrumfieldOnly Moscow rivaled Yaroslavl in its concentration of new churches, sponsored by a combination of wealthy merchants, city districts, and trade associations. During the 17th century, the area’s 35 parishes witnessed the construction of 44 masonry churches, most erected after a fire that consumed much of the town in 1658. Despite damage inflicted during the Soviet era, many of these churches have survived.

Monument to medieval ingenuity

The largest and most elaborate of these structures is the Church of the Decapitation of John the Baptist, located in the Tolchkovo district near the Kotorosl River, a small tributary of the Volga. Prokudin-Gorsky photographed this superb monument only from the west in

Church of Decapitation of John the Baptist, apse. East view. Aug. 15, 2017.

William BrumfieldThe Tolchkovo church was constructed between 1671 and 1687 with funds provided by

The brick facades are

Church of Decapitation of John the Baptist, east facade detail. Aug. 15, 2017.

William BrumfieldGreat ingenuity was demonstrated by the anonymous master builders in the design of the two east chapels, which are dedicated to the Three Prelates (Sts. Basil the Great, Gregory the Theologian and John Chrysostom) and to the Kazan Miracle workers Sts. Gurii and Varsonofii. In an unusual solution, the chapel cornices are elevated to the height of the main structure.

The result is a uniform roof level that creates an impressive visual effect from the west. In Prokudin-Gorsky’s distant view, the relation of the chapels to the main structure is clear. But a closer view, shown in my photograph, hides the chapel structures and creates the illusion that the church is crowned with 15 brilliant cupolas.

Church of Decapitation of John the Baptist, with Holy Gate. Summer 1910.

Sergei Prokudin-GorskyThe chapel structures also create a monumental unity on the east facade, with accent points provided by each chapel's cluster of five miniature cupolas on elongated drums. The decorative relief work on the upper tiers of the east façade is complemented by colorful trompe l'oeil rustication on the lower apsidal structure, divided into five segments. My photographs over the years show that the painted pattern has faded, yet the east facade is no less impressive.

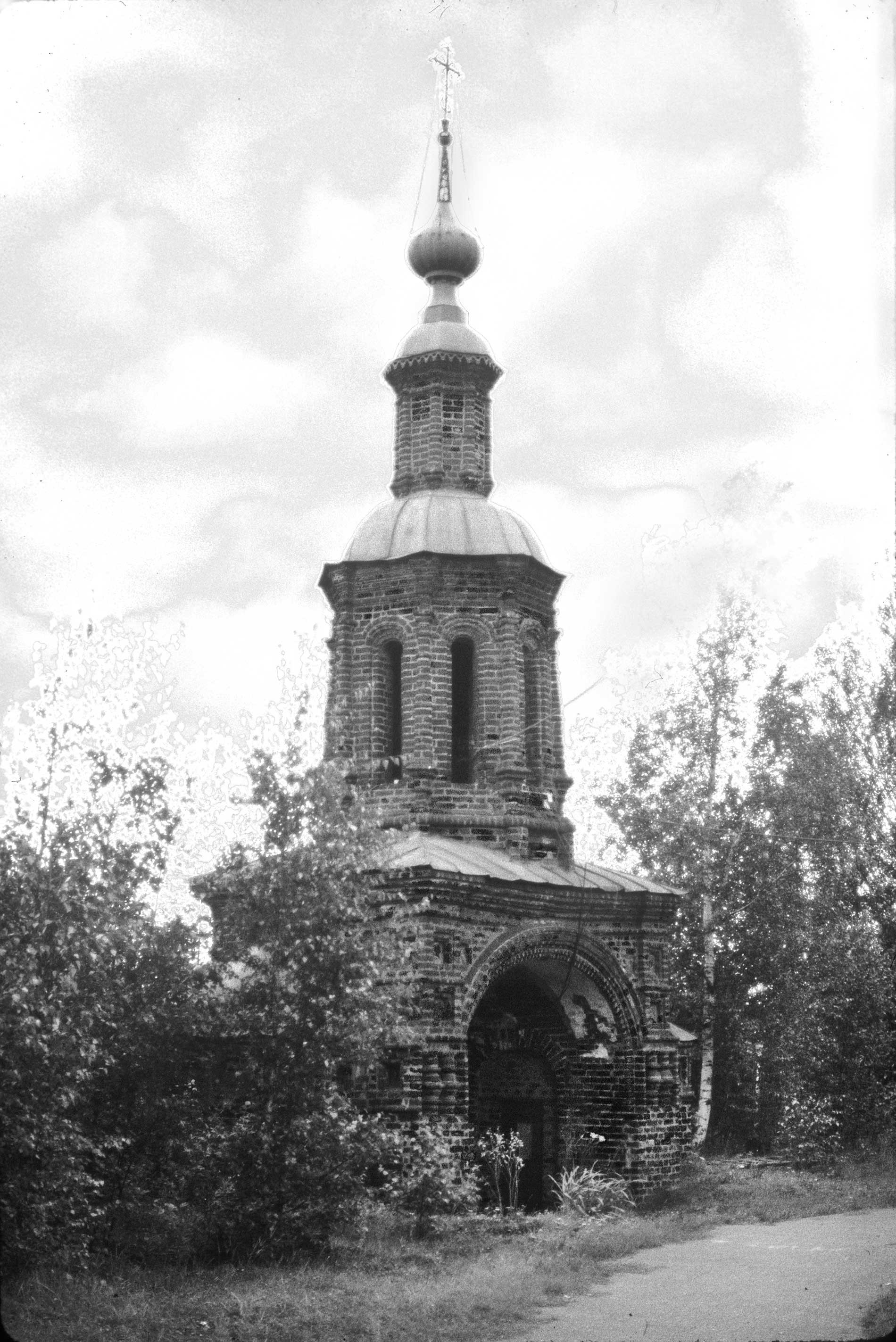

The Church of John the Baptist had ancillary structures, including a modest winter church dedicated to the Ascension, built in 1659-1665 and demolished by the factory in the early 1950s. The main approach to the church from the west was framed by a Holy Gate, which has survived at the factory boundary.

Church of Decapitation of John the Baptist. Holy Gate, southeast view. Aug. 7, 1987.

William BrumfieldThe dominant feature of the ensemble is the bell tower, built at the turn of the 18th century in the florid style known as "Moscow Baroque." This grand campanile, 150 feet in height, is decorated with limestone elements, including balusters and pinnacles that emphasize the ascending octagons — an amalgam of Russian and Dutch design.

In view of the turbulence of 20th-century Russian history, it is something of a miracle that the magnificent Tolchkovo ensemble has, for the most part, survived. As imposing as the Church of John the Baptist is on the exterior, its interior, covered with frescoes, is no less remarkable. Fortunately, we know the identities of the artists who created this space. Their work will be the subject of the following article in this series.

Church of Decapitation of John the Baptist. Bell tower. East view. June 29, 1995.

William BrumfieldIn the early 20th century the Russian photographer Sergei Prokudin-Gorsky devised a complex process for color photography. Between 1903 and 1916 he traveled through the Russian Empire and took over 2,000 photographs with the process, which involved three exposures on a glass plate. In August 1918, he left Russia and ultimately resettled in France with a large part of his collection of glass negatives. After his death in Paris in 1944, his heirs sold the collection to the Library of Congress. In the early 21st century the Library digitized the Prokudin-Gorsky Collection and made it freely available to the global public. Many Russian websites now have versions of the collection. In 1986 the architectural historian and photographer William Brumfield organized the first exhibit of Prokudin-Gorsky photographs at the Library of Congress. Over a period of work in Russia beginning in 1970, Brumfield has photographed most of the sites visited by Prokudin-Gorsky. This series of articles will juxtapose Prokudin-Gorsky’s views of architectural monuments with photographs taken by Brumfield decades later.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox