Yaroslavl’s defining monument: Church of the Prophet Elijah

Yaroslavl. Church of Elijah the Prophet, west view. August 21, 1988.

William BrumfieldOne of the richest historic towns on the Volga River is Yaroslavl, located about 130 miles northeast of Moscow. Now an industrial center with some 650,000 inhabitants, Yaroslavl has a remarkable concentration of church art and architecture from the 16th through the 19th centuries. Each year thousands visit the city on river cruises or by land from Moscow. They all see at least one of the city’s magnificent 17th-century monuments—the Church of Elijah the Prophet, located at the very center of town. The Elijah Church is the consummate example of art sponsored by the city’s flourishing commercial environment.

In summer 1910, the Russian photographer and chemist Sergei Prokudin-Gorsky photographed this surpassing monument. My own photographs of the church cover a span of three decades, from 1987 to 2017.

Yaroslavl. Church of Elijah the Prophet, southwest view. Summer 1910.

Sergei Prokudin-GorskyUnfortunately, no original glass negatives of the Elijah Church are preserved in the collection of Prokudin-Gorsky’s work at the Library of Congress. Nonetheless, one monochrome image from his album of contact prints provides valuable information about the church’s pre-revolutionary state. Taken in the late sun of a summer evening, the photograph provides a sweeping view from the west of the entire complex structure, with the dramatic interplay of light and shadow created by its various forms.

A distinguished history

Yaroslavl was founded at an advantageous point on the Volga River in the early 11th century by the Kievan grand prince Yaroslav the Wise, one of the great rulers of medieval Rus. By the beginning of the 13th century, the settlement had monasteries with masonry churches, a sign of prosperity in those times.

Yaroslavl. Church of Elijah the Prophet, southwest view. August 8, 1994.

William BrumfieldIn 1238, Yaroslavl was sacked by the Mongols during their conquest of central Russia. Although recovery from Mongol dominance was slow, union with Muscovy in the 15th century integrated Yaroslavl into a larger political and economic structure. The town benefited from its location as a center not only for trade within the vast Volga River basin, but also for exploitation of the forested expanses of the Russian north.

In the latter part of the 16th century, Ivan the Terrible established a port at the Archangel Monastery on the Northern Dvina River near the White Sea and thus opened Moscow for commerce with western Europe. This enhanced Yaroslavl’s position within a mercantile network that stretched from the White Sea to Siberia and the Orient. With new trading possibilities, Yaroslavl attracted colonies of Russian and foreign merchants (English, Dutch, and German).

Yaroslavl. Bell tower & Church of Elijah the Prophet, southwest view. Foreground: west entrance porch. Summer 1910.

Sergei Prokudin-GorskyAlthough spared the worst of the disorder inflicted on Russia in the latter part of Ivan the Terrible's reign, the commerce of Yaroslavl declined during the interregnum following the death of Boris Godunov in 1605. Known as the Time of Troubles, this period of political and social chaos saw much of the country plundered.

Yaroslavl, however, eluded the cataclysm and in 1612 served as a rallying point for national resistance against a Polish occupying force in Moscow. The participation of Yaroslavl's merchants in this campaign brought extensive trading privileges during the reign of Mikhail, first tsar of the Romanov dynasty.

Yaroslavl. Church of Elijah the Prophet. West entrance porch with painting of Crucifixion. August 21, 1988.

William BrumfieldMonument to merchant wealth

Throughout the 17th century, the city not only accumulated the wealth necessary to build elaborately decorated churches, but also established connections with cultural centers to the west. Only Moscow could rival Yaroslavl in its concentration of new churches, sponsored by a combination of wealthy merchants, city districts, and trade associations. During the 17th century, 44 masonry churches were erected within the area’s 35 parishes. This is the background for the appearance of the magnificent Church of Elijah the Prophet.

Yaroslavl. Church of Elijah the Prophet. Northeast view with Chapel of Sts. Gurias, Samonas & Abibus of Edessa. July 23, 1997.

William BrumfieldEvidence suggests that an Elijah Church had existed since the early years of the town’s existence. Although that structure disappeared centuries ago, log churches dedicated to Elijah and to the Intercession of the Virgin stood at the center of town in the early-17th century.

In the mid-17th century, both log churches were cleared to make way for a major brick church dedicated to Elijah in the center of the commercial district. The donors of the Elijah Church, the brothers Ioanniky and Vonifaty Scripin, possessed great wealth gained from the Siberian fur trade. They had direct access both to the tsar and to the Patriarch of the Russian Orthodox Church.

Yaroslavl. Church of Elijah the Prophet. Chapel of Deposition of the Robe, west view. Summer 1910.

Sergei Prokudin-GorskyBuilt in 1647-50, the core of the Elijah Church consisted of a massive square structure on an elevated base that also supported an enclosed gallery. The roofline of the main structure originally followed the contours of the arched gables (zakomary), which are still visible despite a simplification of the roof design typical of the 18th century.

The roof is crowned with five domes that support soaring crosses. The central one is a defining example of Russian metal craft. In the 18th century, the green ceramic tiles that originally covered the domes were replaced with sheet metal segments overlapping in a “fishscale” pattern.

The exterior walls were painted with colorful decorative motifs resembling those added in the same period to Moscow's Cathedral of the Intercession on the Moat (popularly known as St. Basil's). Such ornamental display is a hallmark of churches endowed by wealthy merchants in the 17th century. Little of the exterior decoration has survived, apart from the west entrance porch, clearly visible in the evening sun of Prokudin-Gorsky’s photograph.

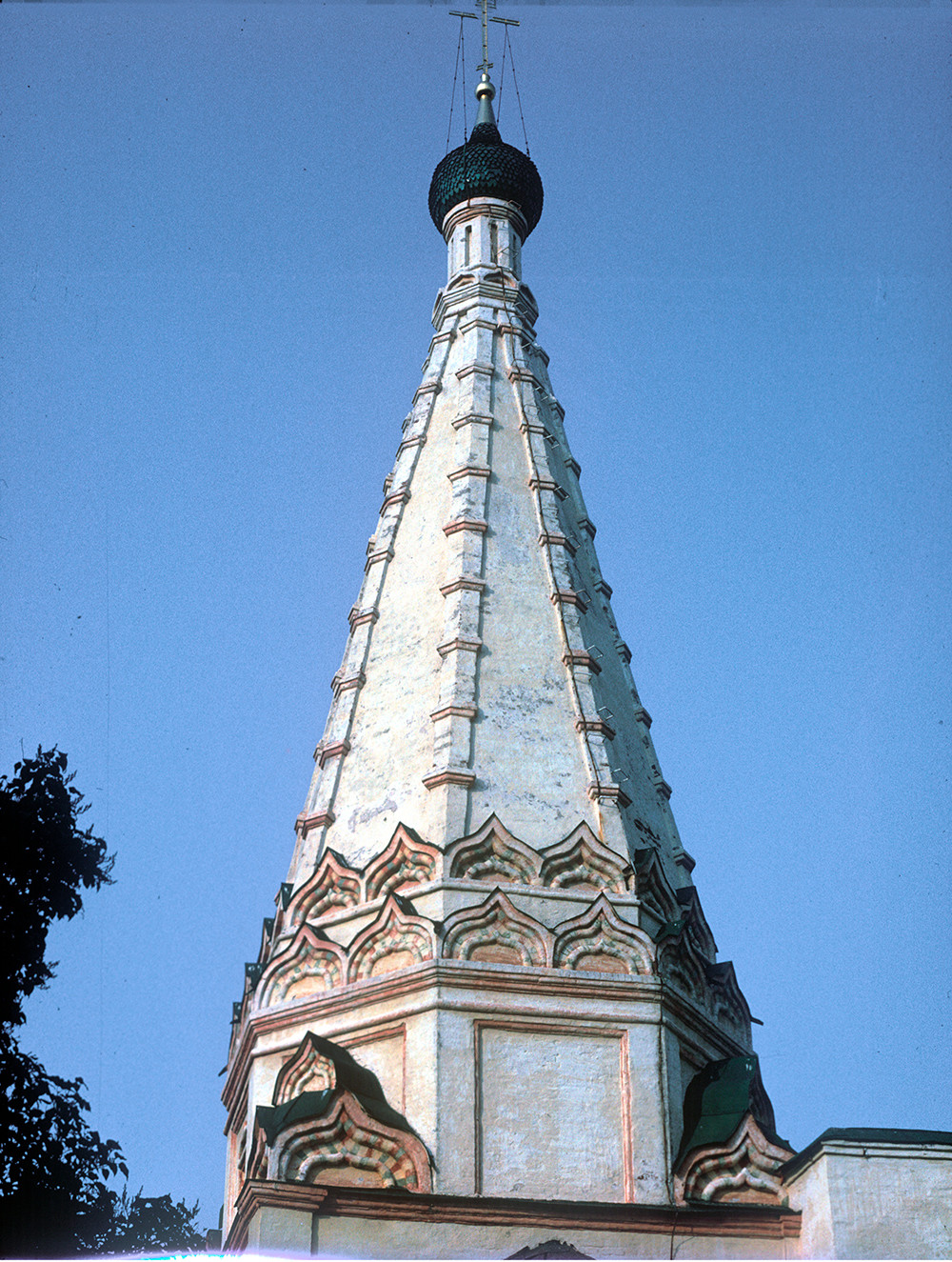

Yaroslavl. Church of Elijah the Prophet. "Tent" tower of Chapel of Deposition of the Robe, east view. July 23, 1997.

William BrumfieldIn the east, the Elijah Church has a three-part extension know as an apse, which contains two altars — one dedicated to the Intercession and the other to St. Varlaam Khutinsky. Like many churches of its period, the Elijah shrine was flanked with structures containing separate altars.

The extension on the north façade forms a small self-contained church dedicated to Sts. Gurias, Samonas and Abibus of Edessa, martyrs at the turn of the 4th who were considered patrons of the family. This structure (not visible in Prokudin-Gorsky’s photograph) is crowned with a pyramid of decorative gables (kokoshniki) that lead to a small “drum” and cupola clad in ceramic tiles.

In 1650, Patriarch Joseph of Moscow gave the Skripins a fragment of Christ’s Robe from the Dormition Cathedral in the Kremlin. In gratitude for this great honor, a separate structure dedicated to the Deposition of the Robe was attached to the southwest corner. Its high “tent” tower provides a strong complement to the tall bell tower attached to the northwest corner. Together they create the unique silhouette of the Elijah shrine.

A great treasure

Yaroslavl. Church of Elijah the Prophet. Northwest ceiling vault & dome with fresco of Mary & Christ Child "of the Sign". Below: fresco of Jesus and the Samaritan Woman at Jacob's Well. August 14, 2017.

William BrumfieldThree decades after the completion of the church, in 1680, the widow of Vonifaty Skripin, commissioned the painting of the interior of the main church by a group of artists led by two of the most accomplished masters in 17th-century Russia - Gury Nikitin and Sila Savin. These splendid frescoes are among the best-preserved in Russia and are valuable as an illustration of a growing secular influence in Russian religious art during the late 17th-century. There is no evidence to suggest that Prokudin-Gorsky photographed the interior of the Elijah Church. I have included some of my 2017 photographs to provide a sense of their vibrancy.

Yaroslavl. Church of Elijah the Prophet. West wall frescoes "Healing of Syrian Commander Naaman by Prophet Elisha" (Naaman bathes in the Jordan River). August 14, 2017.

William BrumfieldAs for the subsequent fate of the Elijah Church, a new town plan implemented in 1778 during the reign of Catherine the Great created a central square that cleared the area around the church, which was now displayed as the town’s crown jewel. In 1902, a decorative fence designed by Andrey Pavlinov was built around the church territory.

With the establishment of Soviet power, the church was transferred in 1920 to the local history museum, which preserved it from demolition in the 1930s. Restoration campaigns have occurred on a regular basis since the 1950s and continue to this day - part of the incessant labor necessary to preserve one of Russia’s greatest treasures.

Yaroslavl. Church of Elijah the Prophet. South wall frescoes "Prophet Elisha Purifies the Waters of Jericho" & "Prophet Elisha Curses the Children who Mocked Him". (Elisha was the successor to Elijah.) August 14, 2017.

William BrumfieldIn the early 20th century the Russian photographer Sergei Prokudin-Gorsky devised a complex process for color photography. Between 1903 and 1916 he traveled through the Russian Empire and took over 2,000 photographs with the process, which involved three exposures on a glass plate. In August 1918, he left Russia and ultimately resettled in France with a large part of his collection of glass negatives. After his death in Paris in 1944, his heirs sold the collection to the Library of Congress. In the early 21st century the Library digitized the Prokudin-Gorsky Collection and made it freely available to the global public. A few Russian websites now have versions of the collection. In 1986 the architectural historian and photographer William Brumfield organized the first exhibit of Prokudin-Gorsky photographs at the Library of Congress. Over a period of work in Russia beginning in 1970, Brumfield has photographed most of the sites visited by Prokudin-Gorsky. This series of articles juxtaposes Prokudin-Gorsky’s views of architectural monuments with photographs taken by Brumfield decades later.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox