Kyshtym in the Ural Mountains: Idyllic landscape, turbulent history

Kyshtym. White House (manor house on former Demidov estate). Main facade. July 14, 2003

William BrumfieldThe factory town of Kyshtym, located 60 miles northwest of Chelyabinsk, is surrounded by the natural beauty of some 30 lakes, including Lake Sugomak, the center of a state nature preserve. The Russian photographer and chemist Sergei Prokudin-Gorsky visited the town in 1909 as part of his project to document the diversity of the Russian empire in the early 20th century.

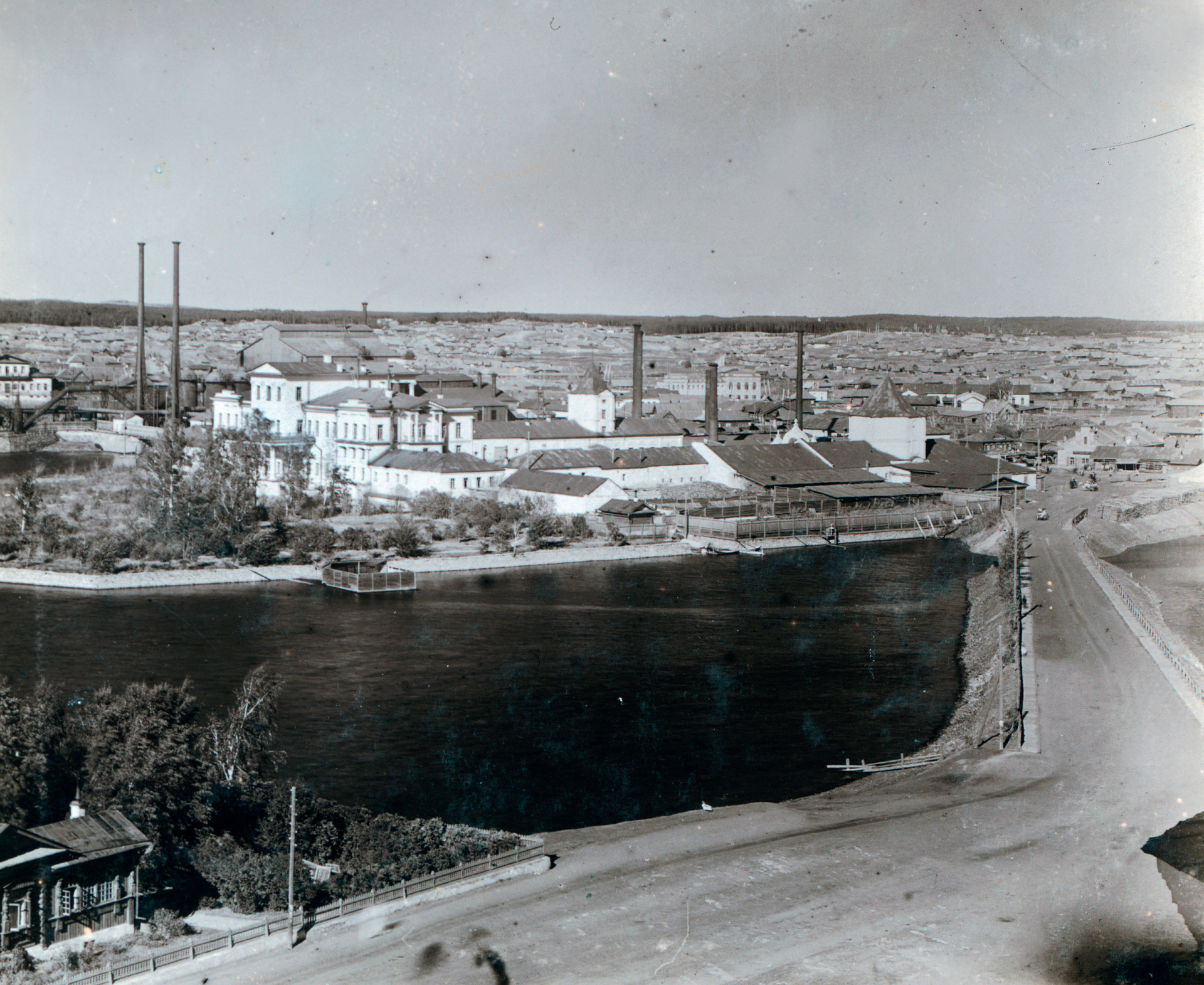

View of main Kyshtym factory with White House on former Demidov estate. Foreground: Town Pond (Kyshtym River). Right: 18th-century tower built by Nikita Demidov. 1909.

Sergei Prokudin-GorskyUnfortunately, the glass negatives of Prokudin-Gorsky’s remarkable Kyshtym panoramas are missing from the collection of his work at the Library of Congress. However, contact prints that he made from the magenta exposure of the original three-part negatives have been preserved. These monochrome images provide much information about this important factory town before the revolution. My photographs of Kyshtym were taken almost a century later, in July 2003.

Prosperity from natural resources

White House. Facade overlooking Town Pond. July 14, 2003.

William BrumfieldIn many ways, the history of Kyshtym parallels that of Kasli, its neighbor 19 miles to the northeast. Both were in areas settled by Bashkirs, and both had a similar geology with access to ample supplies of fresh water, rich mineral deposits such as iron ore and dense forests that yielded charcoal for smelting furnaces.

And as at Kasli, a leading role in the history of Kyshtym was played by Nikita Demidov (1688-1758), youngest son of the elder Nikita Demidov, the patriarch of Russia’s most notable clan in metallurgy. In 1755, he began work on the Upper Kyshtym iron smelter and shortly thereafter on the Lower Kyshtym iron works. These complementary factories began operation in 1757, which is considered the year of Kyshtym’s founding.

Tower on former Demidov estate at Kyshtym factory. Built ca. 1760 by Nikita Demidov. July 14, 2003.

William BrumfieldShortly thereafter, Demidov built an estate house within a compound next to the factory. Parts of the Demidov compound—in particular a large fortress-like tower--have survived and are visible in one of Prokudin-Gorsky’s panoramas as well as in my own photographs.

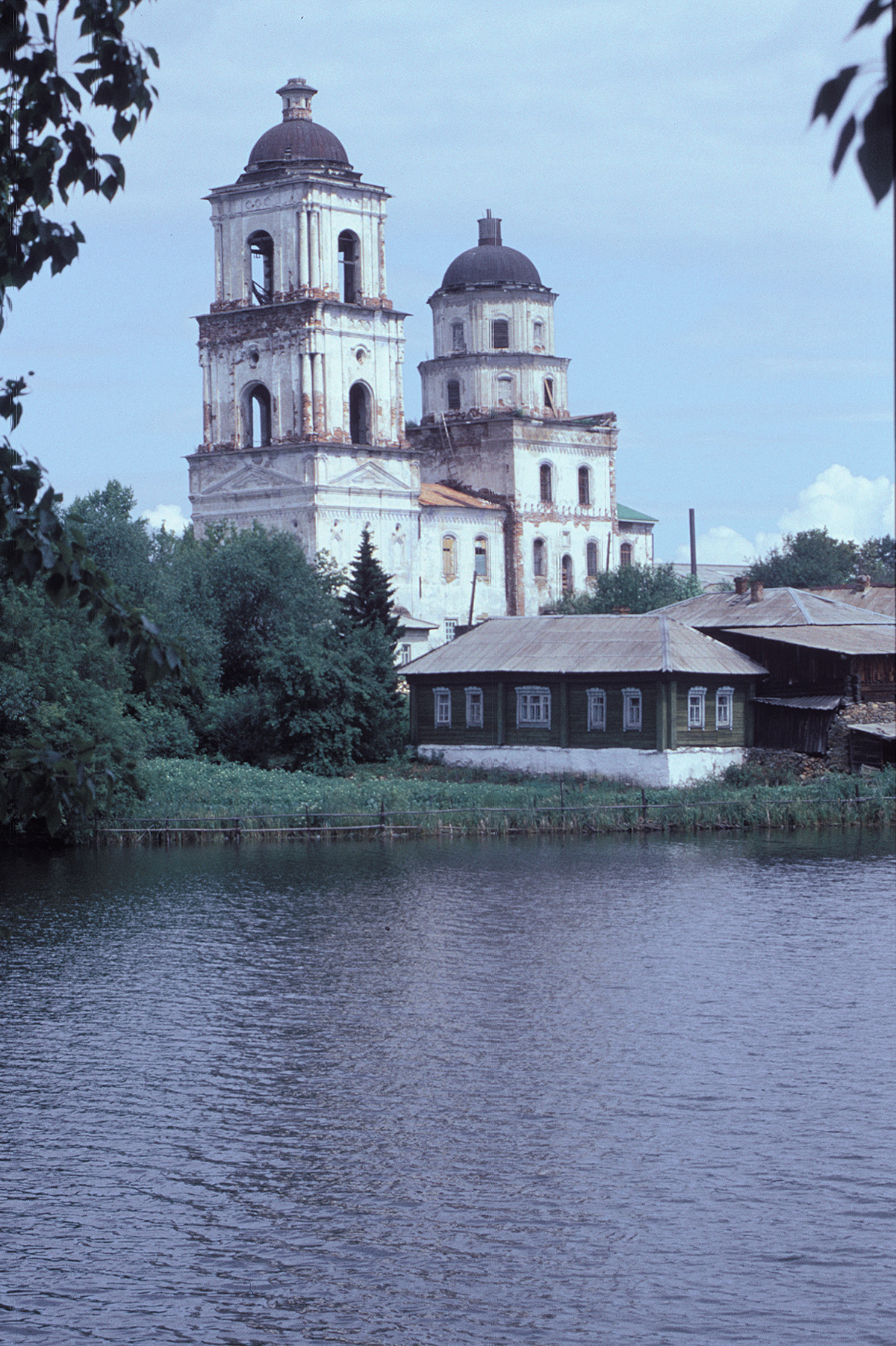

In 1760-64, the Demidovs also built a two-story brick church dedicated to the Descent of the Holy Spirit (the Pentecost), with a secondary altar on the lower level dedicated to the Decapitation of John the Baptist. The church is a simple stacked structure with a single cupola and a large bell tower attached to the west side. Visible in Prokudin-Gorsky’s panorama and in my own views across the factory pond.

View of factory pond, Kyshtym factory & water tower near former Demidov estate. July 14, 2003.

William BrumfieldThe reputation of Kyshtym iron spread under the Demidovs, yet working conditions were harsh. In early 1774, the Kyshtym factories were engulfed by the destructive frenzy of the Pugachev Rebellion that swept through the Urals and the middle Volga region in 1773-74. As at Kasli, the Kyshtym works were burned during the uprising, but by 1776, they had been restored to operation and remained in Demidov hands until the early 19th century.

A century of turmoil

View northeast from roof of White House. Kyshtym factory & secondary tower on former Demidov estate. July 14, 2003.

William BrumfieldIn 1809, the Kyshtym factories — like the Kasli works — were acquired by the Yekaterinburg entrepreneur Lev Rastorguev (1769-1823). Although a devout Old Believer, he made his initial fortune in the wine and spirits trade, and owned numerous taverns.

Rastorguev proved no less adept in the metals business, and the Kyshtym factories flourished during the 1810s. Many factory workers were also Old Believers - Orthodox Christians who were persecuted for refusing to accept liturgical reforms introduced in the 1660s. In Rastorguev they found a protector.

View of workers' houses & garden plots. Background: Kyshtym factory (left), Church of the Descent of the Holy Spirit, Cathedral of the Nativity of Christ. 1909.

Sergei Prokudin-GorskyDuring that decade Rastorguev commissioned the noted Yekaterinburg architect Mikhail Malakhov to rebuild and greatly expand the manor house at the former Demidov compound overlooking the factory pond. The main façade of this magnificent neoclassical structure centers on a portico with two pairs of Corinthian columns facing the courtyard. Large wings extend on either side of this central block. The other side, facing the factory pond, has a lower portico with six columns.

In the 1820s, bad weather and poor harvests exacerbated a flareup of labor unrest in the spring of 1822 over conditions at the Kyshtym factories. Led by the legendary Klim Kosolapov, workers seized control of operations for almost a year in 1822-23 during what was called the “Kyshtym Disturbence.”

Town Pond with Church of the Descent of the Holy Spirit. Right background: Mount Sugomak. July 14, 2003.

William BrumfieldAlthough this largest of 19th-century labor actions in the Urals was suppressed without violent resistance by government troops in March 1823, the shock led to Lev Rastorguev’s death by apoplexy in February of that year. His daughters transferred management to Grigory Zotov, another talented metallurgist and harsh taskmaster, who became known as the “Kyshtym Beast.” Like Rastorguev, Zotov favored Old Believer workers for their sobriety.

The Kyshtym factories’ prosperity was reflected in the construction of a brick Church of the Trinity (1847-49), located adjacent to the main factory and the large Cathedral of the Nativity of Christ (1848-57), whose design closely resembles that of the Ascension Church in Kasli, built at the same time.

Church of the Descent of the Holy Spirit (1760-64). Southwest view. July 14, 2003.

William BrumfieldThe expansion of Russia’s economy after the liberation of the serfs (1861) led to increased demand for the Kyshtym factories. A still greater stimulus was provided by the construction in the mid-1890s of a rail line between Yekaterinburg and Chelyabinsk. With the initiation of regular service through Kyshtym in the fall of 1896, iron and other products from local factories could be delivered by rail, rather than by the laborious, seasonal water route from the Ufa River through the Belaya and Kama Rivers to the Volga.

Kyshtym’s ‘White House’

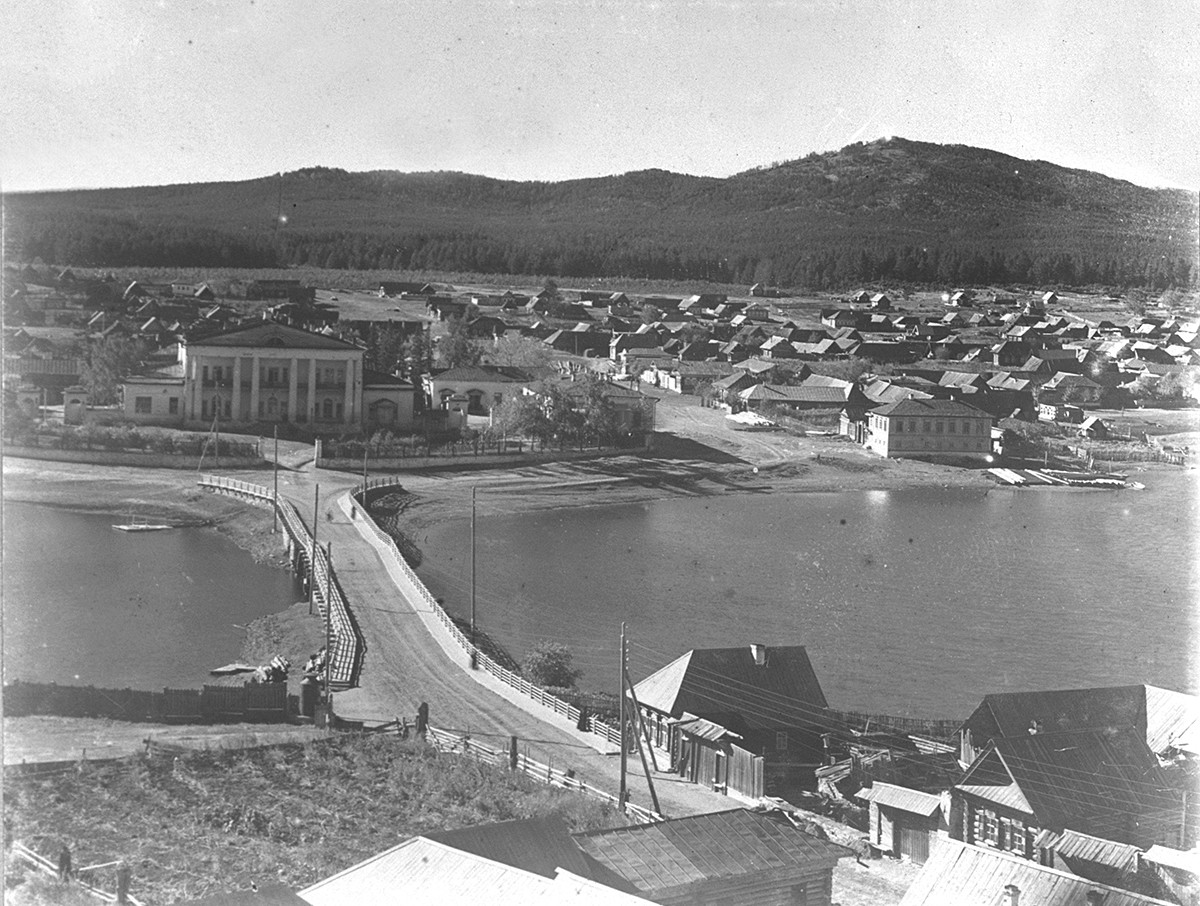

View of Kyshtym factory hospital & workers' settlement. Background. Mount Sugomak. 1909.

Sergei Prokudin-GorskyAt the end of the 19th century, Pavel Karpinsky, general director of the Kyshtym and Kasli factories, converted the White House (as it is popularly known) to a museum. As Prokudin-Gorsky’s 1909 panorama shows, the imposing form of the mansion, with its white stuccoed brick walls, stood in sharp contrast to the surrounding factory landscape.

With the establishment of Soviet power, the mansion was adapted to various educational purposes, and during World War II it served as the temporary home of Leningrad’s renowned Herzen Pedagogical Institute from the spring of 1942 to the summer of 1944. Only in 1979 did the mansion regain its museum function, but decades of neglect had taken their toll.

View of Mount Sugomak from roof of White House. July 14, 2003.

William BrumfieldMaintenance of such a grand monument was beyond the resources of a modest museum, and the mansion slipped into a ruined state visible in my 2003 photographs. In 1995, the White House became one of the rare buildings in the Urals region to be designated a Federal Landmark, and a campaign for preserving the abandoned mansion was supposed to begin.

Resources, however, were far less than the amount needed for proper restoration. An attempt in 2015 to revive the project as a hotel venture with private investment has also apparently stalled, and the fate of this superb landmark remains uncertain.

Revolution and restoration

Local Administration (zemskaya uprava) building (19th-century). Right: late 19th-century log house with iron roof (example of workers' housing). July 14, 2003.

William BrumfieldIn the early 20th century Kyshtym’s cultural development was reflected in the building of a People’s House (Narodny dom), part of a network of educational centers throughout Russia that encouraged the spread of enlightenment and societal consciousness. Usually supported by local governments, the number of People’s Houses increased rapidly after the 1905 revolution.

Prokudin-Gorsky would have seen an earlier, wooden version of the Kyshtym People’s house, opened in 1903 in a donated factory warehouse. The new People’s House, built in 1913 after a fire destroyed the original, was converted to a Palace of Culture and a theater during the Soviet period. This delightfully eclectic building reopened in 2017 as a cultural center after almost a decade of renovation efforts.

The decade following Prokudin-Gorsky’s visit treated Kyshtym harshly: World War I, revolutionary upheavals, civil war, hunger. The culminating disaster was a fire in 1921 that destroyed a third of the largely wooden town and left thousands homeless. With government assistance Kyshtym’s factories were rebuilt by 1925.

After World War II, Kyshtym’s industrial base gained new importance with the establishment of a Soviet program to overcome American hegemony in atomic weapons. A closed, top-secret settlement (now known as Ozyorsk) was created 6 miles to the northeast for the development of a reactor and the processing of nuclear fuel.

People's House (Narodny dom), built in 1913. July 14, 2003.

William BrumfieldOn September 29, 1957, lax safeguards led to the explosion of a storage facility at the Mayak (“lighthouse”) processing plant in Ozyorsk. The resulting release of radioactive matter would be exceeded on Soviet territory only by the Chernobyl disaster almost three decades later. Because of the secret nature of the site, the tragedy, which affected dozens of surrounding villages, became known as the “Kyshtym Catastrophe,” after the nearest known town.

Over a century after Prokudin-Gorsky’s visit, Kyshtym - the “peaceful wintering site of the Bashkirs - remains suspended between two polarities. On the one hand it retains its industrial significance with the demand for strategic metals driven by the realities of international politics. On the other hand, there is a drive to stimulate tourism based on the natural beauty of the Sugomak Nature Preserve, centered on Mount Sugomak, Sugomak Cave and Lake Sugomak, which Prokudin-Gorsky photographed in the setting sun.

Lake Sugomak after sunset (nature etude). 1909.

Sergei Prokudin-GorskyIn the early 20th century the Russian photographer Sergei Prokudin-Gorsky devised a complex process for color photography. Between 1903 and 1916 he traveled through the Russian Empire and took over 2,000 photographs with the process, which involved three exposures on a glass plate. In August 1918, he left Russia and ultimately resettled in France with a large part of his collection of glass negatives. After his death in Paris in 1944, his heirs sold the collection to the Library of Congress. In the early 21st century the Library digitized the Prokudin-Gorsky Collection and made it freely available to the global public. A number of Russian websites now have versions of the collection. In 1986 the architectural historian and photographer William Brumfield organized the first exhibit of Prokudin-Gorsky photographs at the Library of Congress. Over a period of work in Russia beginning in 1970, Brumfield has photographed most of the sites visited by Prokudin-Gorsky. This series of articles will juxtapose Prokudin-Gorsky’s views of architectural monuments with photographs taken by Brumfield decades later.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox