In a country far, far away… How did a filmmaker in the USSR inspire Hollywood blockbusters?

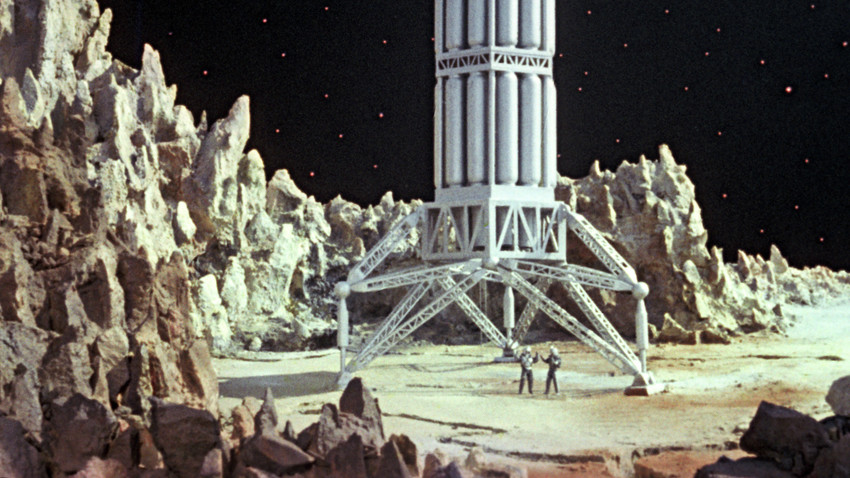

A screenshot from Road to the Stars movie by Pavel Klushantsev (1957, USSR)

SputnikA popular legend circulates in the Russian film industry that in 1988 George Lucas supposedly visited Moscow for the premiere of his second Star Wars film, The Empire Strikes Back. The American filmmaker wanted to meet Pavel Klushantsev, but Soviet officials had never heard of him. Lucas considered Klushantsev the godfather of the Star Wars saga, but unfortunately the two never had the chance to meet. Klushantsev eventually died in 1999.

So who was this mystery man? He was a genius filmmaker, writer and inventor of hundreds of film production methods and special effects that are still used in the film industry. Traces of his innovations can be found in many movies, such as Titanic, Terminator 2, 2001: A Space Odyssey, and Prometheus.

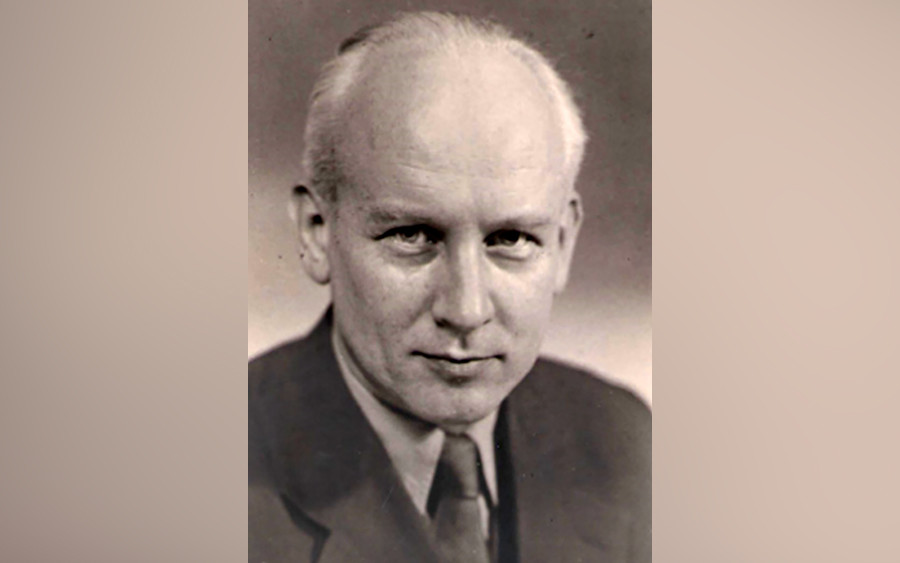

Pavel Klushantsev

Michael KlushantsevPioneering a new genre

Films such as Road to the Stars (1957) and Planet of Storms (1962) were groundbreaking for their time, and were even bought by Americans and adapted for local audiences. In America, Planet of Storms became Voyage to the Prehistoric Planet (1965), starring both American and Soviet actors. A second film, Voyage to the Planet of Prehistoric Women, followed three years later, and featured a race of women on the planet Venus.

One of the Soviet filmmaker’s key achievements was pioneering a new genre – documentary science fiction. Every detail in his films was made to be as real as possible so that the audience believed the story could possibly be true.

An example of this can be seen in Road to the Stars with the realistic night sky and the correct positions of stars, which was created thanks to a seven-meter board with lamps of varying brightness placed in accordance with a true star map.

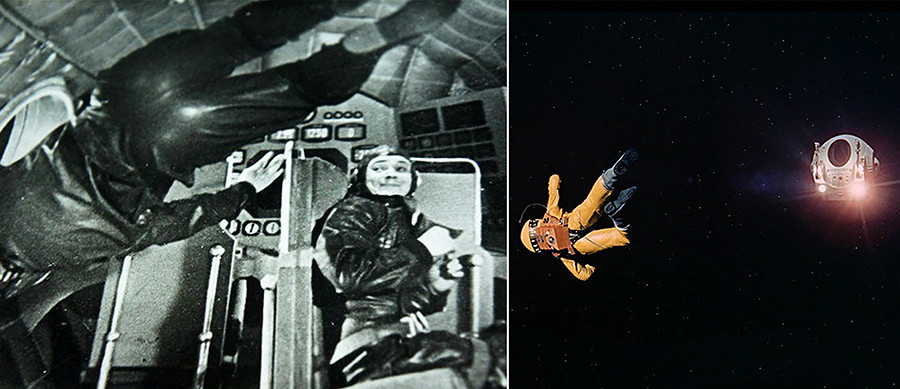

The first antigravity scene in history was filmed by Klushantsev with the help of a few steel ropes and a right camera angle. A similar approach was used by Stanley Kubrick as well.

Pavel Klushantsev's Planet of Storms (1957) and 2001: A Space Odyssey by Stanley Kubrick, 1968 (right)While Hollywood was impressed with Klushantsev’s works, this wasn’t true in the Soviet Union, where his work was often met with suspicion. Soviet authorities were more concerned with ideology and delivering a social message.

At the beginning of Klushantsev’s career, when he applied for state support for Road to the Stars, officials answered: “These space flights will not happen in the next 200 years! We need to shoot movies about how to boost beetroot production.”

Eventually the film got state support, but suspicion remained the general attitude to his plans. Still, while his studio was chronically underfunded, Klushantsev found numerous ways to create the unimaginable on screen by being exceptionally creative with only a handful of tools. He pulled off the first antigravity scene in film industry history, with just a steel rope and a camera!

Decades later the American film director and editor, Robert Skotak, an Academy Award-winning specialist in visual effects, wrote to Klushantsev, who was living in a tiny apartment in St. Petersburg after retiring in 1972. Skotak said he was writing a book on the history of visual effects and had as many as 50 questions after watching Klushantsev’s movies.

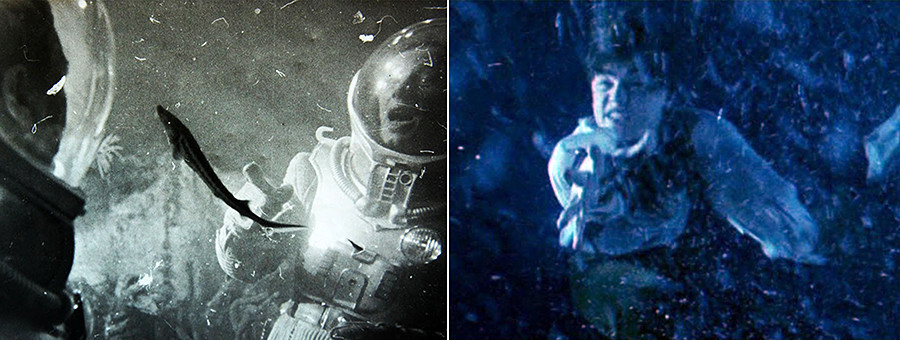

Klushantsev filmed through an aquarium with fish to achieve an underwater effect. A similar approach might have been used in Titanic, which Skotak worked on later.

Pavel Klushantsev's Planet of Storms (1957) and Titanic by James Cameron, 1997 (right)The Soviet film innovator, who kept busy writing books for children, was happy to answer Skotak, who he finally met in 1992. “The Americans with their big time expensive film shooting equipment and studios couldn’t figure out the things we did using just a few wires and ropes,” Klushantsev remarked.

According to his daughter, the Soviet genius never asked for money when his innovations were used abroad, and he never received anything from Hollywood. “Skotak said that in America they have expensive equipment, but few creative people, and in this respect my father was outstanding,” Klushantsev's daughter Zhanna remembers.

The first scene in history with a robot dying in lava was done by Klushantsev with the use of tinted dough. A similar scene occurs in Terminator 2, which Skotak also worked on.

Pavel Klushantsev's Planet of Storms (1957) and Terminator 2 by James Cameron, 1991 (right)Still, it would be incorrect to say that all American blockbusters were made thanks to Klushantsev. Zhanna pointed out that his technologies and instruments are more a starting point for modern moviemaking. His movies might seem a bit naïve to the modern viewer, but when considering the period and situation of the era that his films appeared – when the general public knew little about space – they do make a strong impression.

Noble origins

Born in 1910 in a noble family living in St. Petersburg, Klushantsev witnessed the Revolution and the Civil War. In 1919, he lost his father, and his mother could only find work at an orphanage opened in an abandoned estate outside of St. Petersburg. There, Pavel spent much time playing, and at some point he discovered a book on yachts and quickly fell in love with them. He studied it thoroughly and even began to create his own model yacht. He also was fond of fireworks, and even learned how to make gunpowder.

At the age of 14, Klushantsev began working, doing all sorts of things, from giving math lessons to making chess figures and selling them. His dream was to be an engineer, but his noble past was an obstacle for acceptance into university, so he decided to work in the film industry as a cameraman – a profession where it wasn’t necessary to have an unsullied class history.

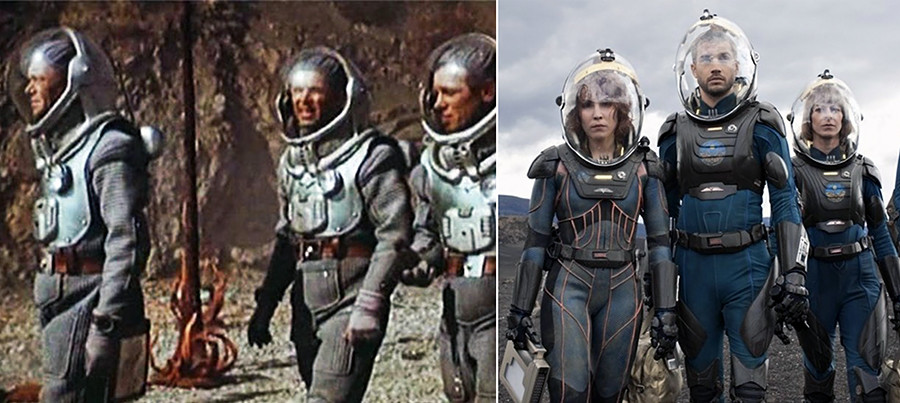

The space suits designed by Klushantsev were reportedly used in the design of actual Soviet space suits in which cosmonauts travelled to space. So it's natural that similar costumes appear in modern films.

Pavel Klushantsev's Planet of Storms (1957) and Prometheus by Ridley Scott, 2012 (right)After World War II, when Klushantsev had been shooting military documentaries, he decided to direct movies, starting with Polar Lights, a documentary that no experienced professional wanted to undertake because no one knew how to capture the northern lights on film. Klushantsev found a way to do it by devising a machine that could perfectly capture the polar lights in a way that allowed them to be depicted in their full glory. No one could understand how he did it.

Then his friend suggested making a movie about space travel, based on the work being done in secret scientific labs. He did, and the result was Road to The Stars that premiered in 1957, which coincided with Sputnik’s launch. At a time when the public knew little about space the movie was a hit, offering answers to common questions: How is space travel even possible, and what does this mean for the future?

Klushantsev first came up with a flying antigravity vehicle for his 1957 movie. A similar version appears in Star Wars. Coincidence?

Pavel Klushantsev's Planet of Storms (1957) and Star Wars. Episode IV: A New Hope by George Lucas, 1977 (right)“Everything was secret, so we had to create a movie with our models and come up with engineering designs on our own,” recalled Klushantsev, who found a way to invent hundreds of production methods and special effects. “After that we kept working and began to think about what will be possible in the future. Our films for the first time in history captured the docking and landing of spaceships, the first space flight and the first Moon voyage.”

All his predictions looked 30 years into the future, and eventually they were very close to reality. The rockets in Klushantsev’s films, for instance, were almost identical to the real ones that Soviet engineers secretly worked on. Therefore, it was no surprise that the director was closely watched by security services. But he successfully avoided problems by proving that he invented all the decorations and models in his films.

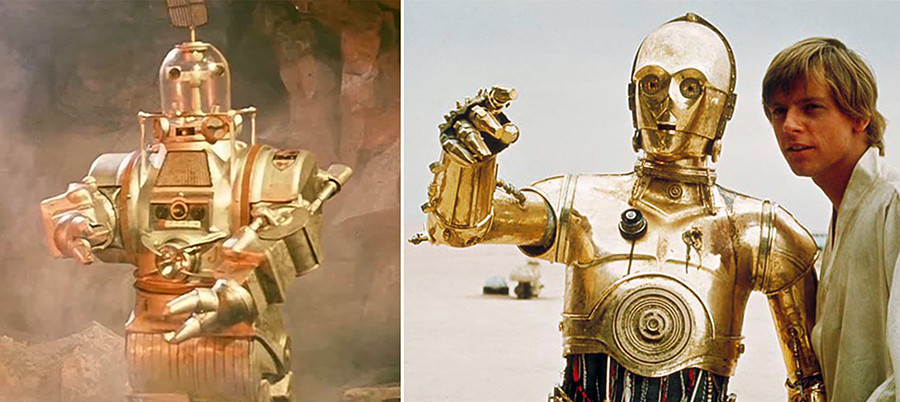

Klushantsev also first pictured a robot as a friend of a human space crew. Like a C-3PO it was also managed by a human actor inside of a robot costume.

Pavel Klushantsev's Planet of Storms (1957) and Star Wars. Episode IV: A New Hope by George Lucas, 1977 (right)Klushantsev’s could do things that no one could do, and this helped him remain unscathed in an unstable time when people with noble background could easily be jailed, or even killed. As his daughter recalled, he understood quite well that the only thing that could save a person from exile or prison, even an innocent one, was to be the best in his profession.

“Dozens of times they tried to kick me out of the film studio and send me to prison, but I survived because I knew how to do things that no one else could do,” said Klushantsev.

Want to know more about other important films in the history of Russian cinema? Take a look at Harvard's top 10 Soviet and Russian films - definitely worth watching on a weekend.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox