Why did a Russian writer encourage people to get drunk on suburban trains?

Venedikt Yerofeyev's fans celebrate his 60th anniversary on a train from Moscow to Petushki.

Boris Kavashkin/TASSEven though he produced few literary works, writer Venedikt Yerofeyev incited Russians to think about themselves and their lives. He knew Soviet life

‘We will downright perish’

What

His friend, the poet Olga Sedakova, says, “his drinking was symbolic… Denial of the social structure was his choice. And many friends and younger admirers followed his way of life – ‘We will downright perish.’”

Olga Sedakova, poet and Venedikt Yerofeyev's friend

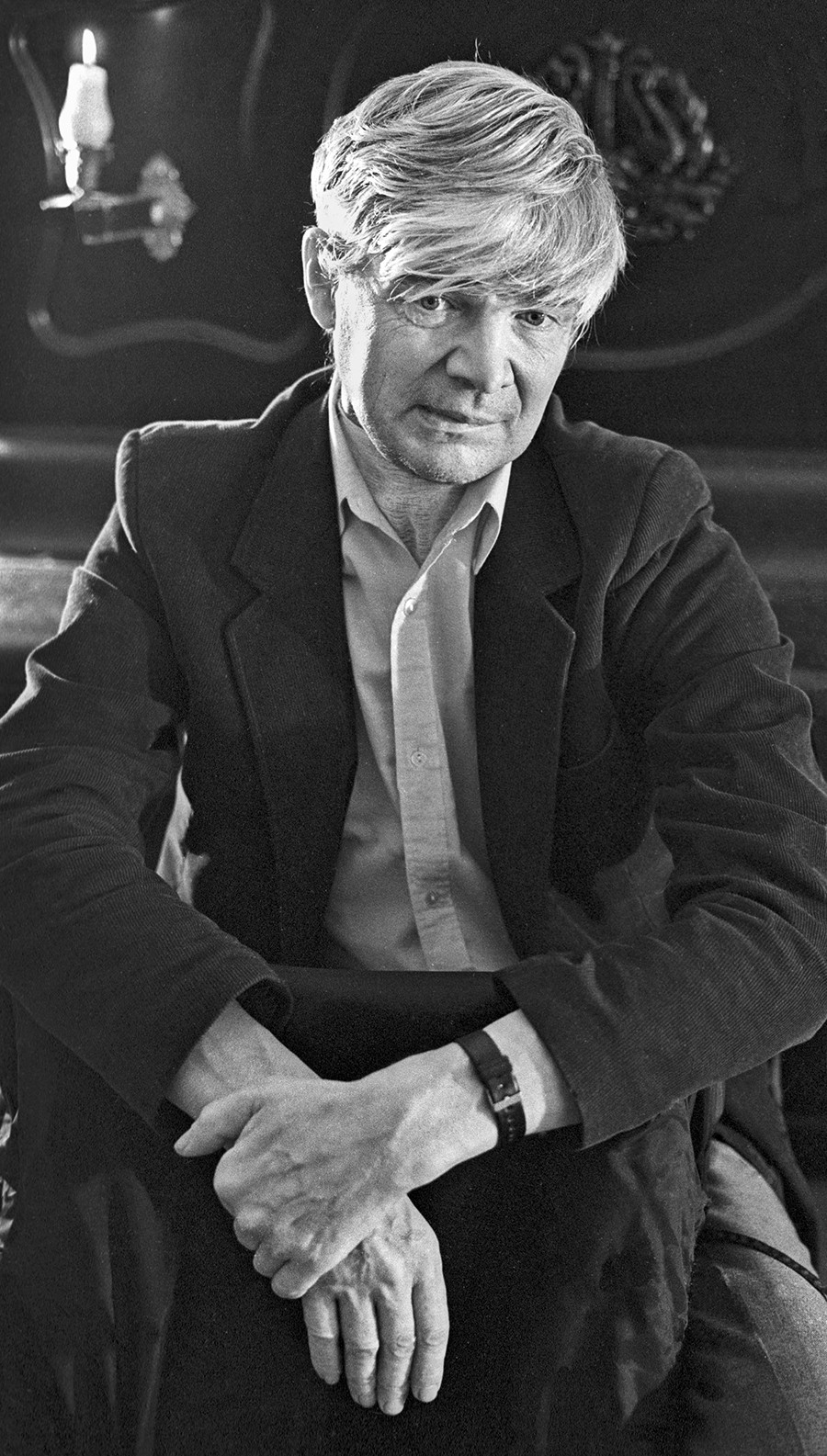

Viktor Tolochko/TASSAfter Yerofeyev was expelled from Vladimir State Pedagogical Institute (he read the Bible to his groupmates and wrote anti-Soviet poetry), the KGB set its sights on the rebel young writer. Apart from the Bible, he knew Latin and adored classical music and literature that were not in Soviet university curriculums. Yerofeyev shared his knowledge with his fellow workers, friends, and acquaintances, forming an inner circle. Yerofeyev, however, escaped imprisonment by, again, drinking.

When his friend, Vladimir Muravyev, was asked by KGB officers what Yerofeyev was doing, the answer was: “Drinking all day, just as he always does.” After that, the secret services supposedly put Yerofeyev’s papers in the back of the shelf. Venedikt did much to conceal his real self, and the main thing was his recurring myths.

Fact and fiction

“Moscow To The End of The Line” was first popular in samizdat in the 1970s, and even more popular after it was officially published in the late 1980s. It was a “novel about a guy who gets drunk on the train,” which was easily relatable for Soviet citizens. As the author bitterly noted, nobody understood the tragedy behind the book. They thought it’s just a hilarious story, and treated it and the author accordingly. Viktor Kulle, a poet and Yerofeyev’s acquaintance, recalled a literary evening in 1987: “He shoved off people like pesky flies, it was apparent that he’s tired, but everybody thought that when talking to him it’s compulsory to swear very loud and offer him drinks…”

Yerofeyev tried to baffle his fans with riddles and constructed myths about his works. It’s amusing that these myths were meant to send fans looking for something that was never there: a recurring theme in Russian traditional folk tales, by the way.

First: there was a lost chapter in “Moscow To The End of The Line” that consisted only of obscenities that were cut, and only “And I drank it straight down” was left. Philologists went to great lengths to find a chapter that never existed. Another myth was about “Dmitry Shostakovich,” the novel he wrote and then supposedly lost on the train. Yerofeyev’s schoolmate, Slava Len, even published an excerpt from the novel, but literary historians are sure that it’s also a hoax.

Yerofeyev reportedly led thousands of people to drink, and Sedakova reckons that just as Goethe’s “The Sorrows of Young Werther” started a suicide epidemic in the late 18th century, Yerofeyev’s book drove many people down the alcoholic drain.

“Those young people who read it not very

Perhaps the fin-de-siecle attitude of the late Soviet period was useless in the new life – a life that Venedikt detested and wanted nothing to do with.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox