Russia's most lovelorn writers

The role these writers play in literature is defined by their artistic and philosophical heritage. A writer’s talent should not be underrated if his/her personality doesn’t fit public opinion on moral standards, including traditional perception of love in society. On the contrary, unusual love conflicts and practices may be great catalysts for the creative process.

Alexander Pushkin

Alexander Pushkin, Natalia Goncharova

Orest Kiprensky/Sputnik, Global Look PressLet's start with the writer who is called "our everything" by Russians. It’s a far cry from how he referred to himself: "What a Pushkin, what a son of a bitch!". However, it was just a way to express a writer’s satisfaction from his own talent when he finished his drama in verse "Boris Godunov".

The author of numerous brilliant poems, incredible prose and admirable dramaturgy, Pushkin was an outstanding womanizer as well. Perhaps his passionate temper was influenced by his African blood. The poet's great-grandfather was of African birth, who was abducted and later became a favorite of Peter the Great - the first person of African origin known to have lived in the Russian Empire.

Pushkin started to devote his poems to the ladies when he was very young, and even made a list of 37 women’s names, later taking Don Juan as an example. Despite this, Pushkin was married only once - to Natalia Goncharova. When he suspected her of having an affair Pushkin challenged his rival to a duel, who fatally wounded him.

Read more about women loved by Pushkin

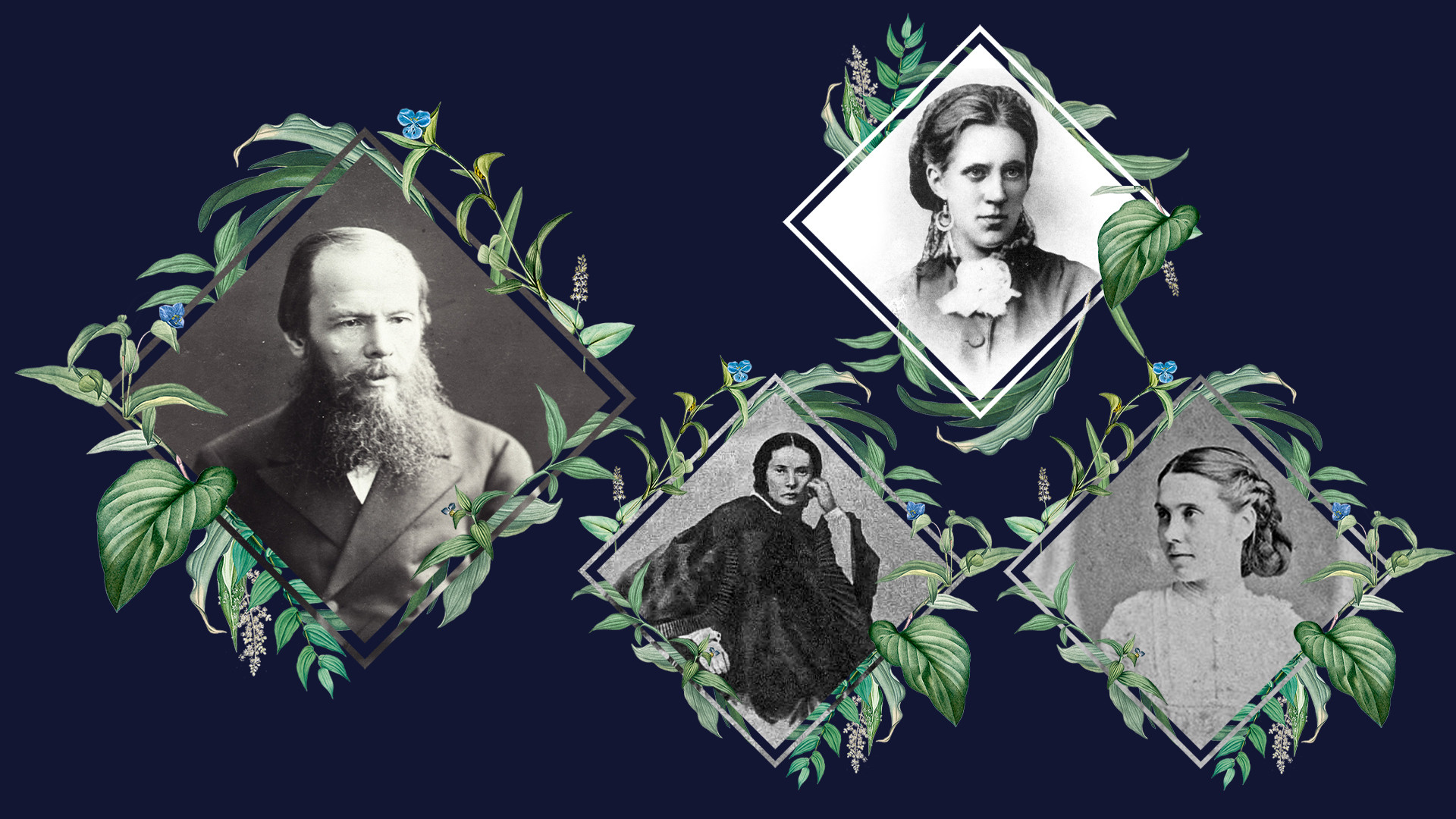

Fyodor Dostoyevsky

L-R: Fyodor Dostoevsky, Maria Dostoevskaya, Anna Snitkina, Appolinaria Suslova

Global Look Press, ArchiveBeing very nervous and introverted, Dostoevsky tended to frequent prostitutes. He was very self-critical about this and although he feared disease, just could not stop himself. “I'm so dissolute that I cannot live a normal life,” he wrote to his brother.

Dostoevsky met his first wife, Maria Isayeva, in Siberia during his exile. It was her second marriage. Before the wedding she enjoyed teasing Dostoevsky sometimes saying that she’d better marry a richer man. Eventually, she felt sorry for the oppressed Fyodor and married him. Their wedlock was not long lasting and brought the writer much pain. Dostoevsky wrote that they loved each other immensely, but could not be happy together. Plus, his epilepsy intensified. Maria died of tuberculosis at the age of 39.

In 1862, Dostoevsky visited some European health retreats resorts, but instead of mineral water and mud baths, he chose gambling and roulette, becoming addicted. He spent most of his time in the company of the so-called “infernal woman”, free-spirited Appolinaria Suslova. Their relationship was complicated and nervous; she caressed him and at the same time could slap her lover. However, Dostoevsky, as we know, loved to suffer. Their affair became the inspiration for his novel “The Player”.

The writer's last wife, Anna Snitkina, was his employee, a stenographer employed to help him while he was working on “The Player”. In 1867, they were married, though Anna was 25 years younger than Fyodor. She gave birth to four children but the writer remained a very jealous man.

Read more about Dostoevsky, turbulent in love and life

Maxim Gorky

L-R: Maxim Gorky, Ekaterina Peshkova, Maria Andreeva, Moura Budberg

TASS, Sputnik, Public Domain, Getty ImagesThe great proletarian writer was unlucky in love: women did not find him appealing. When he was young he even tried to commit suicide because of his loneliness. In his autobiographical novel, “Once in Autumn” a bitter first sexual experience is probably a prototype of his own one: he got it with a prostitute and it happened underneath an upturned boat on a river bank.

Officially, Gorky’s wife was Catherine Peshkova (Peshkov was actually Gorky’s real surname). They had a son.

For more than 15 years, Gorky had an affair with Maria Andreeva, an actress at the Moscow Art Theater. She broke up with famous philanthropist and millionaire Savva Morozov to be with Gorky. Her “ex”, by the way, was Maxim’s friend, and, surprisingly, was not offended by the couple’s reunion and even continued to provide Andreeva with money.

Together with the actress Gorky traveled to the United States. Their trip became a great scandal as journalists found out that Russian lovers were not officially married, and Gorky’s actual wife was waiting for him in Russia. Puritanical Americans kicked the couple out of the hotels they stayed in, and other hotels also refused to provide accommodation.

Another interesting lady in Gorky’s life was Moura Budberg. She was highly likely a double agent of British intelligence and the NKVD. After splitting up with Gorky, she had a long lasting affair with H.G. Wells, whom she met in Gorky's house.

Find out the reasons why Soviet writer Maxim Gorky is so great

Sergey Yesenin

L-R: Sergei Yesenin, Galina Benislavskaya, Isadora Duncan, Zinaida Reich

TASS, Global Look Press, Public Domain, Getty ImagesThis Russian poetic “hooligan” had a big heart. He always fell in love immediately but his ardor also quickly cooled. Even as a young peasant boy, he managed to find himself in the chambers of noble landowner Lydia Kashina, who had an estate in his village Konstantinovo in Ryazan Region. At the age of 18, Yesenin became a father, though he wasn’t officially married to the woman who gave birth.

Three years later, in 1917, he married actress Zinaida Reich. She gave birth to a daughter and when she was pregnant with a son, Yesenin left her. The poet’s children were adopted by Reich’s second husband, the theater director Vsevolod Meyerhold.

After splitting up with Reich, Yesenin lived with his literary secretary, Galina Benislavskaya. The nature of their relationship is not crystal clear, but Galina clearly loved Yesenin her entire life - when this “hooligan” committed suicide she shot herself beside his grave.

In 1921 Yesenin met American dancer Isadora Duncan and married her a year later, although she was almost 20 years older and did not know Russian, while Esenin did not speak English. Together they traveled to Europe and America where he felt envious and lonely because of his wife’s popularity. He just couldn’t stand life in the shade of a famous dancer. Their marriage lasted about two years, and was rarely free of both scandal and passion.

In 1925, Yesenin married Leo Tolstoy's granddaughter Sophia, however, their marriage did not last even a year as it was unhappy. Those, who think that Esenin died from a suicide, consider loneliness to be one of the main reasons for this tragic decision.

(By the way, in the short “unmarried gap” between Isadora and Sofia, translator and poet Nadezhda Volpin managed to give birth to a son by Yesenin).

"Many women loved me, and I loved more than one, too": Read more about Sergei Esenin

Anna Akhmatova

L-R: Anna Akhmatova, Nikolai Punin, Nikolai Gumilev, Amedeo Modigliani

Getty Images, ru.openlist.wiki, Getty Images, Public DomainThis woman had so many affairs, that even Yesenin may have felt envious. (By the way, he really wanted to meet her and showed interest in her not only as a talented poet, but as charismatic woman, but Akhmatova, alas, was in love with another man).

Her first husband was Nikolai Gumilev, they were both outstanding poets of the Silver Age of Russian culture and members of the same literary circle. Their son Leo Gumilev would become a famous ethnographer.

The couple spent their honeymoon in Europe, where Akhmatova became a close friend of the artist Amedeo Modigliani. Later she argued about rumors of their affair, saying that they were just close friends, although she posed for him naked many times.

Gumilev and Akhmatova’s marriage quickly became an open relationship. Anna fell in love with other people, and Nikolai too. There was a lot of gossip about Akhmatova's affair with the artist Boris Anrep. There was no evidence for this, except the numerous love poems that Anna dedicated to him. As a response, the artist captured Anna’s image on the famous mosaic at the entrance to the National Gallery in London.

After eight years of marriage, in 1918, Akhmatova and Gumilev divorced, although they had not lived together for a long time already, but divorces and later marriages could be held, in fact, only after the October revolution. In 1918 Anna married again to another poet - Vladimir Shileyko. However in the spring of 1921 Anna and Vladimir broke up, and in the summer of 1921 her first husband Nikolai Gumilev was shot as he was suspected of participating in anti-Bolshevik terror.

In 1922, Anna became the common law wife of the critic Nikolai Punin, despite the fact that she divorced Shileyko officially only in 1926. The love union with Punin was the longest and strongest in Akhmatova’s life but even this one could not last forever.

In 1939 she fell in love with pathologist Vladimir Garshin, but their relationship was interrupted by the war, the siege of Leningrad and later evacuation. When Anna returned to Leningrad, she broke off the relations with Garshin.

Read more about the legendary Russian poet Anna Akhmatova

Marina Tsvetaeva

L-R: Marina Tsvetaeva, Sofya Parnok, Sergei Efron, Boris Pasternak

Getty Images, Public Domain, Global Look PressMarina met her future husband Sergei Efron in the house of the poet Maximilian Voloshin in Crimea. It was a key gathering point for the creative intelligentsia, and during the Civil War it was a good shelter for them. Marina and Sergey were married in 1912 and had a daughter, Ariadne.

In 1914 Tsvetaeva left her husband and become "just friends" with the translator Sophia Parnok (and probably the first ever noted Russian lesbian). Their affair was a kind of obsession, but eventually Tsvetaeva returned to her husband and described same-sex love as a boring.

Tsvetaeva is said to have a short affair also with another genius of the Silver Age of Russian culture - the poet Osip Mandelstam. This relationship was not something special for both of them, however, the arrival of Mandelstam from St. Petersburg to Moscow to see Marina influenced them as poets and this influence can be found in their great poems.

Tsvetaeva’s official husband Efron volunteered to take part in the Civil War (as an officer of the White Army). In 1920 their second daughter Irina died at the age of three in an orphanage. Marina left her there, thinking that she would be taken care of, but the poor child starved to death.

Tsvetaeva moved to Prague where she had an affair with a close friend of Efron, Konstantin Rodzevich. However, he soon married another woman.

In 1926 Russian literature’s most unusual epistolary love story began. This was the triangular correspondence of Boris Pasternak, Marina Tsvetaeva and Austrian poet Rainer Maria Rilke. Rilke died in the same year and Tsvetaeva continued to correspond with Pasternak. The epistolary lovers saw each other only once and the author of “Doctor Zhivago” was not impressed by the “real” Tsvetaeva.

Read some other intriguing facts about Tsvetaeva that you can’t find on Wikipedia!

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox