Yuri Olesha: The king of metaphors smashed by Stalin’s social realism

Yuri Olesha was one of the least prolific Soviet writers. His works could be counted on the fingers of one hand. He wrote one outstanding novel, one brilliant fairy tale, one mediocre play, one small collection of stories and one book of a genre invented by him - a book of diaries about how he could no longer write. Only two books saw the light of day during his lifetime. But that was already enough to call Olesha a genius.

The last man of the century

Olesha had talent aplenty as a writer, poet, satirist and even a football player. Born in 1899 in Ukraine, he proudly referred to himself as “the last man of the century”. His father was an impoverished Polish nobleman. Olesha lived his middle-class childhood in Odessa (home of fellow writer Isaac Babel) and began writing poetry in school.

The author of Envy, Yuri Olesha.

SputnikYuri was one of the best students in class and showed early promises in football, which had just started to gain momentum. But after one match the school doctor said Olesha had a weak heart and forbade him to play football. “That was when I realized what a ban meant for the first time in my life,” Olesha later recalled.

READ MORE: Top 3 Jewish writers who clashed with the Soviet system

In 1917, he entered university, where he studied law for two years. Like a number of the other youths, he welcomed the Bolshevik Revolution like a new baby, with anticipation. In 1920, following years of unrest, Soviet leadership had been finally established in Odessa. Olesha dreamed of traveling the world, going to Germany, France and Italy. In 1922, while his parents emigrated to Poland, Yuri decided to move to Moscow. He wrote satirical essays for the railway workers’ newspaper ’Gudok’ (“The Whistle”), writing under the pen name ‘Zubilo’ (“The Chisel”.)

The king of metaphors

Olesha was known for his biting humor. “My life was a series of events,” he once recalled. “For example, there was a day of [Leo] Tolstoy’s death and the day I saw a girl reading Anna Karenina on a subway escalator.”

Olesha was often referred to as the king of metaphors, each a thought-provoking rib-tickling delight.

“His muscles moved under his skin like rabbits swallowed by a boa constrictor,” he wrote. Or: “The doctor clutched at his heart, which was jumping like an egg in boiling water.”

“The puddle lay under the tree like a gypsy.”

“The yawning shook me like a dog.”

According to Soviet fiction writer Konstantin Paustovsky, who was nominated for the Nobel Prize for literature three times, there was “something Beethovenian in Olesha, even in his voice. His eyes discovered many marvelous, impressive things around him and he wrote about them briefly, precisely and excellently.”

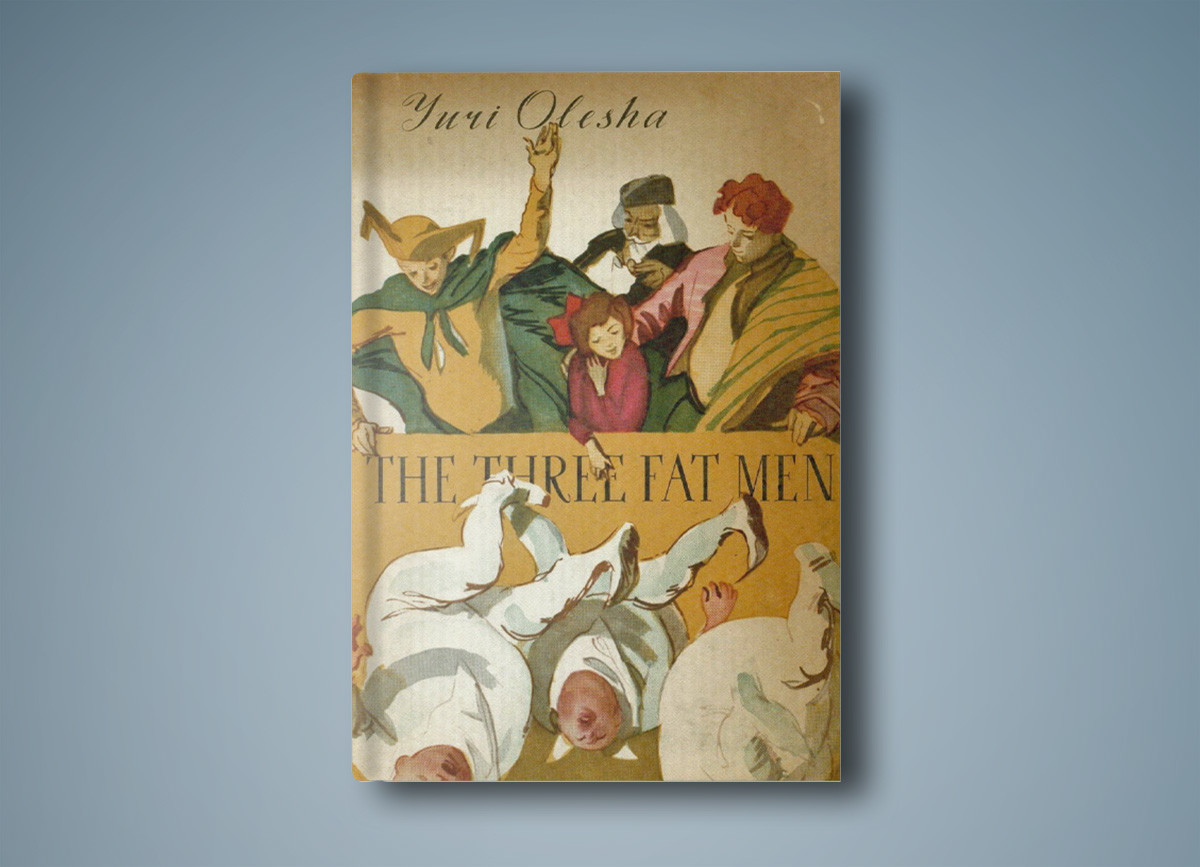

The Three Fat Men

Fame hit Olesha fast and hard, right after ‘The Three Fat Men’ fairy tale came out.

Legend has it, in spring 1924, Olesha was looking out the window when he saw a girl aged about 13. She was reading Andersen’s fairy tales. Olesha was fascinated by the teen to the point where he made a promise to write the “best fairy tale in the world” and dedicate it to her. That promise gave birth to ‘The Three Fat Men’, written for both children and adults.

Olesha wrote The Three Fat Men for both children and adults.

Progress Publishers, 1982The story is set in an unknown fictional land and focuses on an uprising led by the gunsmith Prospero (whose name is obviously an allusion to Shakespeare’s magician from ‘The Tempest’). Echoing the 1917 Revolution, Olesha’s novel is set in a country ruled by insatiable and greedy aristocracy, with the Three Fat Men in the limelight. They have a boy named Tutti who is meant to become their heir. The poor romantic creature is not allowed to have contact with other children, his only companion is a doll named Suok. The pig-like men also build a zoo with wild animals to teach Tutti his first lesson in cruelty.

Olesha deliberately walked on a tightrope at a time when one wrong step took your whole career with it. His novel revealed as many strata as French mille-feuille, filled with signature witty metaphors and layers of hidden meaning.

The pinnacle of Olesha’s literary career

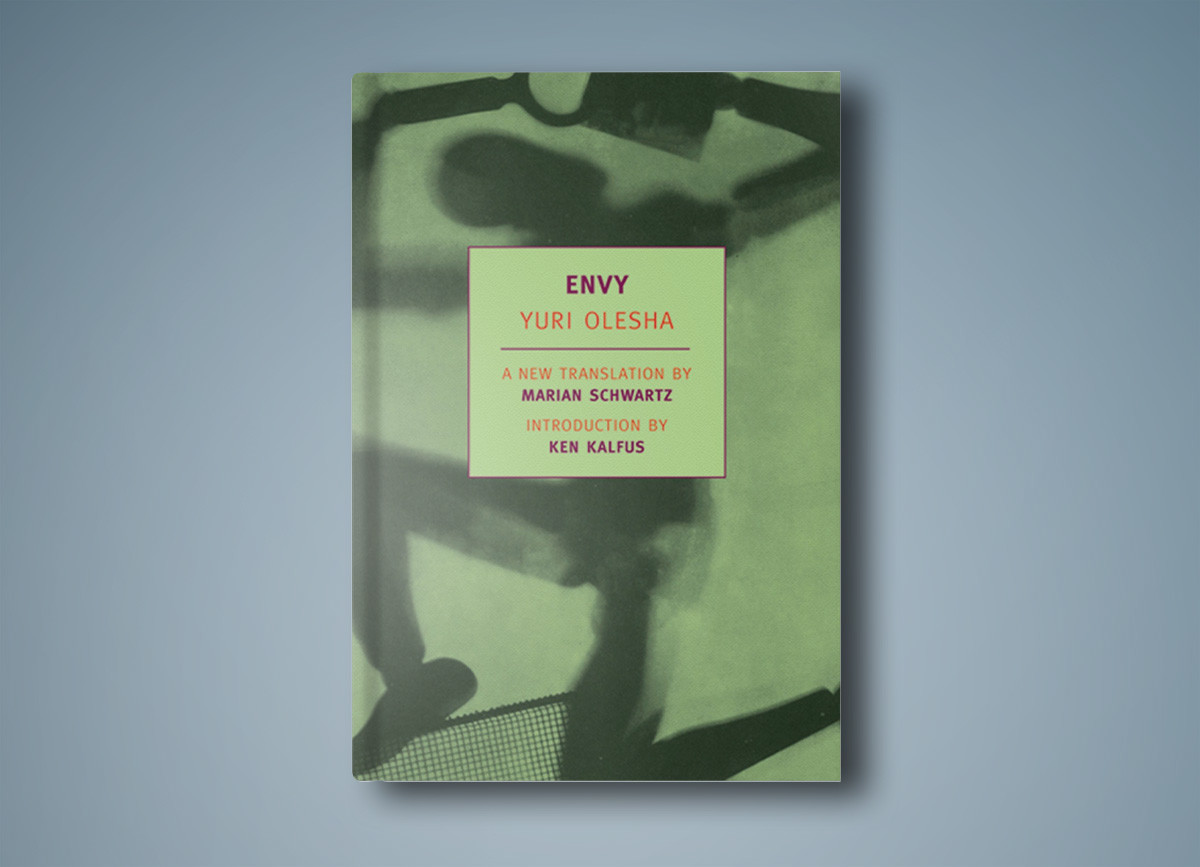

Three years later, in 1927, Olesha’s next masterpiece ‘Envy’ was published in the Krasnaya Nov' magazine. Many literary critics called it the pinnacle of his literary career, and one of the greatest works of 20th Century Soviet literature.

Literary critics called 'Envy' the pinnacle of Olesha's career.

New York Review Books Classics, 2004Nikolai Kavalerov, the protagonist of the novel, is an intellectual, a dreamer and poet, who becomes an outsider in both worlds, to be precise, a loser in Soviet reality. Goal-oriented and successful manager of a meat factory Andrei Babichev is his direct opposite. The failure to succeed in the new world, where inhumane laws tend to dominate, make the image of Kavalerov autobiographical. Nikolai Kavalerov was Olesha’s own alter ego. In his tour de force, the writer created a metaphor of the Soviet system, with the much-loved Bologna becoming a symbol of Soviet prosperity.

New Soviet reality

By the early 1930s, Olesha had published a series of short stories and plays, including ‘A List of Benefits’. The play was staged by the trailblazing Soviet theater director Vsevolod Meyerhold.

For many years, Olesha worked on his memoirs, published posthumously as ‘No Day Without a Line’. It’s a potpourri of sketches, essays, pictures and diaries, often compared to ‘A Writer’s Diary’ by Fyodor Dostoyevsky. “I don’t know much about life. What I like most is that it has animals, large and small; that it has dome-shaped stars sparklingly looking at me from a clear sky; that it has trees like beautiful paintings and much and much more.”

Yuri Olesha (third from left) with members of the literary circle at the Likhachev plant.

Elizaveta Mikulina/SputnikThe notion of “social realism” (which was imposed by Joseph Stalin following Lenin’s death and basically forced artists to create nauseatingly optimistic pictures of Soviet life) went against Olesha’s values and beliefs. He became addicted to alcohol.

“I can’t write any more. If I write that the weather was bad, they will tell me that the weather was good for cotton,” Olesha told Ilya Ehrenburg, a fellow writer. In Soviet times, the fear of becoming a social pariah was palpable. He wanted to write, but didn’t know what to write about.

Yuri Olesha in 1954.

Alexander Less/TASS“I, a Soviet writer, ask myself a question: what have you done for the proletariat? I have done nothing for the proletariat. I write novels, essays, short stories, poems and plays. I pose questions, work out problems, cover aspects of life and so on. I get published, distributed and read. [And it’s all a lie.] It’s okay. On the surface. There is no doubt that everything that I have written is completely uninteresting and unnecessary for the proletariat. These are intellectual subtleties, delights… everything I could have written if the proletarian revolution had not happened,” Olesha wrote in his diary.

In the 1930s, the writer’s colleagues and friends were arrested, sent to labor camps, some of them executed. Olesha somehow avoided this fate. During the war, he lived in evacuation in Ashgabat, the largest city in Turkmenistan. The writer returned back to Moscow only in 1947.

READ MORE: Andrei Platonov: The genius who supported communism but mocked the Soviet system

The last years of his life were spent at the restaurant of the legendary House of Writers, where Olesha was often found sipping vodka. He was broke.

Once, having learned that there were different funeral ceremonies for different Soviet writers, he asked how he would be buried. They told him his funeral would be expensive. Olesha, who never lost his sardonic sense of humor, asked whether it was possible to make the future funeral dirt cheap and give him the difference, already.

He didn’t have to wait long. Olesha died of a heart attack in Moscow in 1960 and was buried at the Novodevichy cemetery.

READ MORE: 10 books that were banned in the USSR

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox