Slavic pagan mythology had its own explanations of important cosmogonic and anthropological questions, including how the world and various natural phenomena originated, where man came from and why he is the way he is. Slavic mythology was more akin to Scandinavian and ancient Indian mythologies.

In Ancient Russia, everyone knew that the main god was Perun, the thunder-bearer and patron of the prince's military retinue. He brought the rain which made the soil fertile, but he could also split a tree in two with lightning.

Prince Oleg and his retinue take an oath to the god Perun in 907

Public domainPerun resided in the sky, but had a long-standing conflict with Veles, who lived on earth and looked after agriculture and livestock. Veles was also the patron of monetary transactions and trade. It is believed that after the adoption of Christianity the "function" of Veles was taken over by St. Nicholas the Wonderworker, who became one of the most popular saints in Old Russia - he was regarded as someone more or less close and familiar. Various and purely Russian interpretations of the image of St. Nicholas appeared, and many people even forgot that he was an early Christian saint from Byzantium.

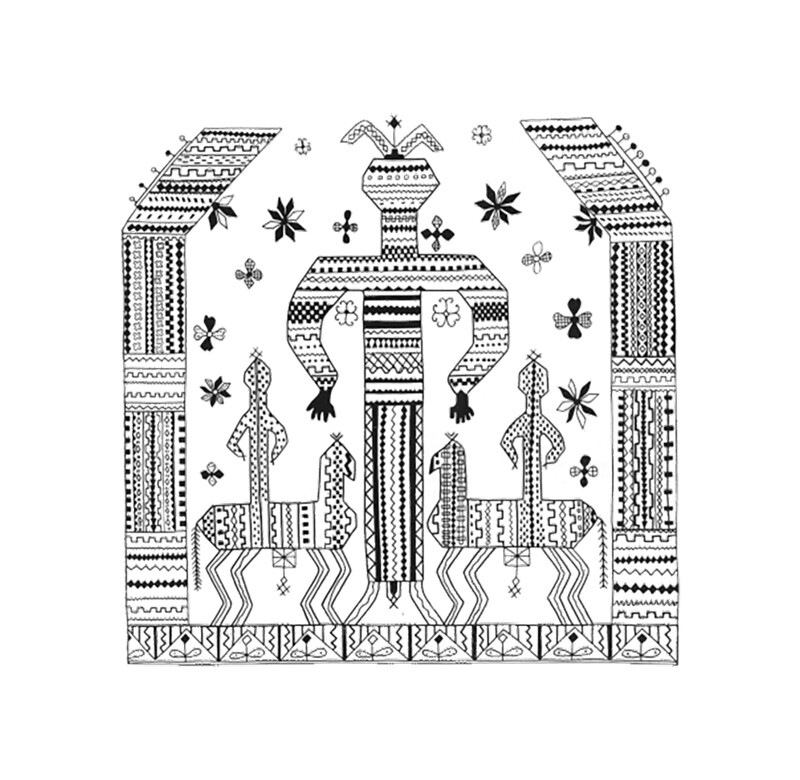

An image of Mokosh on North Russian embroidery

Public domainKhors was the sun god, Dazhbog the god of fertility and Stribog the god of the wind and the air. There was a female deity, Mokosh, who presided over the feminine side of things, and was the protector (and favorite deity) of women, particularly mothers. She was also the goddess of weaving, crafts and worldly blessings generally.

Russia adopted Christianity at the end of the 10th century. The complex texts of Holy Scripture, however, were inaccessible to most people. Originally, they were in Greek and the priests explained them during services (and often each clergyman did so within the limits of their own understanding and education).

Prince Igor takes an oath in front of a figure of Perun, while Christians take an oath at the Church of St. Elijah

Public domainHaving been deprived of the pagan gods and idols, many people still needed answers to the most important questions of life and sought an explanation for various natural phenomena. Often, it was impossible for common folk to comprehend how everything that happened was the will of God, and they needed more descriptive examples of how everything "works" on Earth.

Furthermore, until the 17th century the country had been acquiring new territories in the Urals and Siberia, where the indigenous population was still pagan and transmitted their own understanding of the world, of man and the gods.

Even today, Russians still have many superstitions and popular beliefs about evil spirits and about the power of natural phenomena. Many Orthodox holidays were even "adapted" from pagan traditions (like Maslenitsa - the week before Lent) to make it easier for Russians to get used to the new customs.

Oral tales also began to appear, blending new Christian concepts with old and familiar mythological and folkloric elements. One of the well-known written texts providing answers to these questions in Ancient Rus was the Glubinnaya Kniga ('Profound Book'), or, as it was more frequently referred to, the Golubinaya Kniga ('Book of the Dove'). The dove was a symbol of the Holy Spirit and of peace.

In essence, the 'Book of the Dove' is one of the so-called apocryphal texts. Anyone who read such a text could be declared a heretic and could be punished. This is what happened to St. Abraham of Smolensk, who lived in the late 12th/ early 13th centuries.

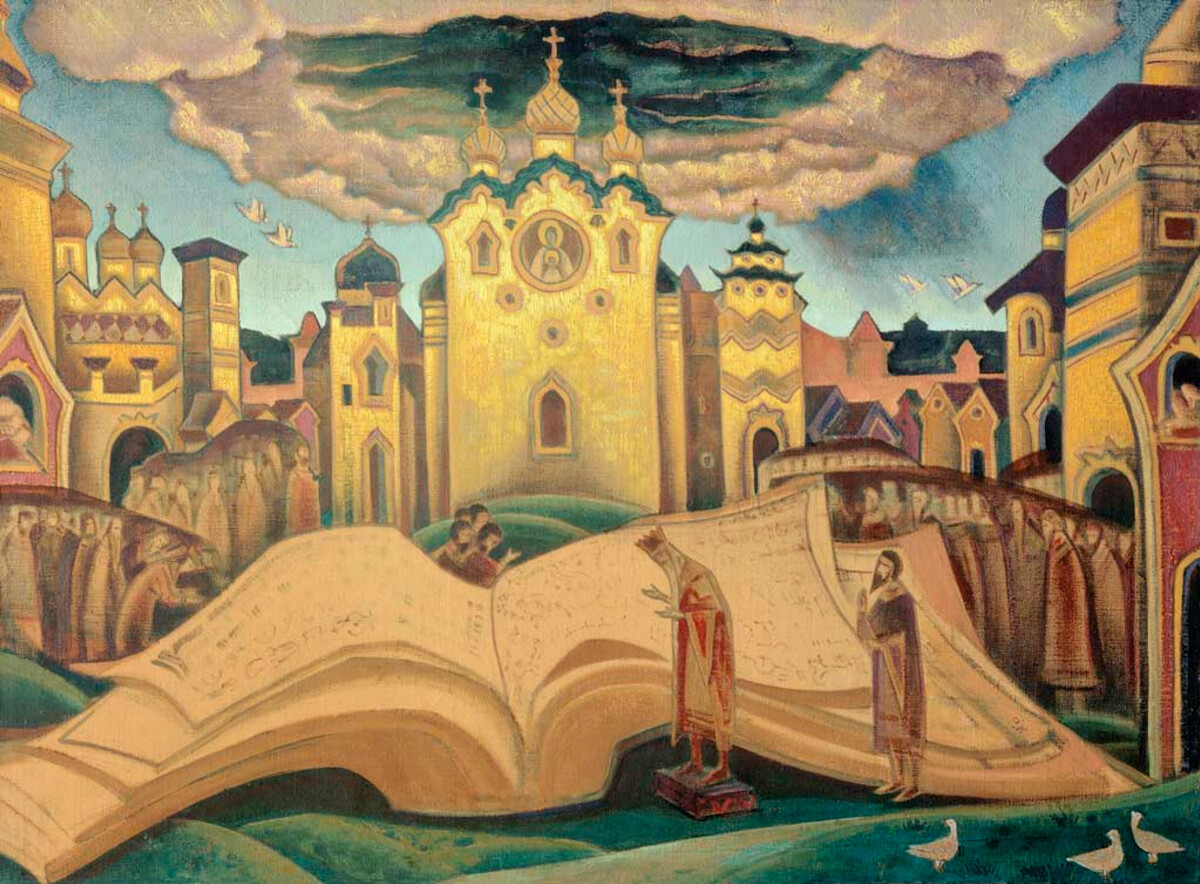

Nicholas Roerich. The kings of the Earth reading the Book of the Dove, 1922

Public domainHe was banished from his monastery and publicly put on trial by the church authorities for reading apocrypha and "profound" books and giving excessively "guileful" sermons which drew large audiences. He wrote books. For instance, it is known that he penned "Sermon on the Heavenly Powers… and the Fate of the Soul", which contains reflections on important spiritual issues.

It is not known for sure when the 'Book of the Dove' first originated. The first discovered written versions date to the 17th century, but scholars believe that the text emerged earlier - in the late 15th/ early 16th centuries. In form, the verse is very similar to the sagas in the Old Russian folk epic tradition of the bylina.

The book consists of three parts. The first describes the origin of the text. An enormous book is said to have fallen straight from the sky and a great throng of people gathered around it, but they were all afraid to come close. The book opened by itself as soon as the wise Tsar David Yevseyevich approached (probably a coded name for the biblical King David). And he told the people that the book was written by Christ himself, and that it was read by the Prophet Isaiah.

In the second part, people ask David to find answers in the book to questions they’re interested in "concerning our life and Holy Russia", and about the origin of different things - the sun, the rain, clouds, the sun, the stars, the night, and so on. There are also spiritual questions - from where did man get his "intellect and reason" and ideas. There are separate questions about how the tsars, princes, boyars (nobles) and Orthodox Christian peasants originated.

Nicholas Roerich. The Book of the Dove (In Remembrance of the Four Kings), 1911

Public domainDavid says that the Sun comes from the face of God, the wind from the Holy Spirit and the rain from the tears of Christ, and, for instance, man's thoughts from the heavenly clouds. Also according to the book, the White Tsar (i.e. the Russian tsar) takes precedence over all the tsars. He stands up for the Christian faith and for the house of the Mother of God (i.e. Rus). And the Holy Land of Rus is the mother of all lands.

He also speaks of Jerusalem and how Christ was crucified, but at the same time he refers to completely folkloristic things - the Whale-Fish, the Stratim-Bird and the Indrik-Beast.

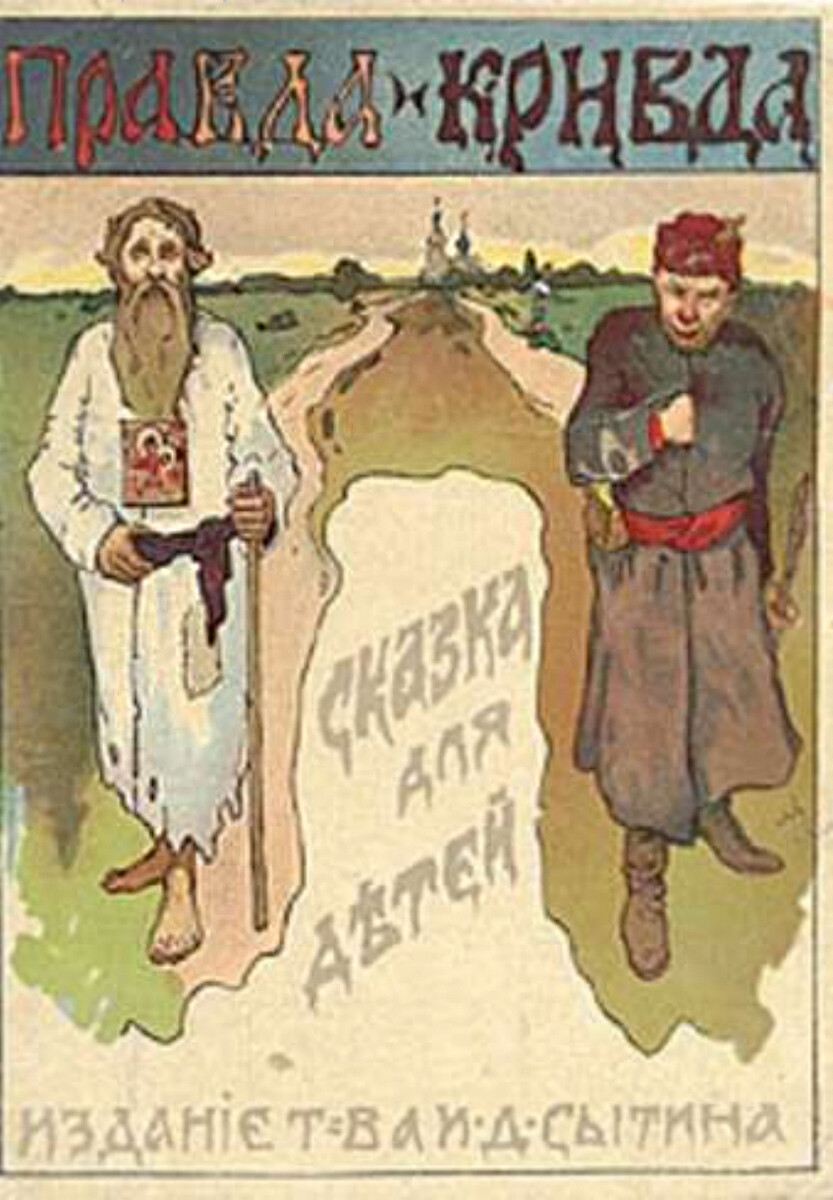

Finally, the third part narrates the dream of David, in which the battle of Truth and Untruth took place. Truth triumphed and outwitted her opponent in debate, and went to the heavens to the presence of Christ himself, while Untruth spread over the earth, and was the source of all problems and the reason why people are "wayward". Here is how, in passing, David explains the essence of faith: "Who does not live in Untruth/Is pleasing to the Lord."

Truth and Untruth. Tale for children

Public domainIn addition, David - concisely and very freely in bylina style - retells the biblical narratives of Creation and how Eve was tempted by the "perfidious serpent".

The 'Book of the Dove' essentially laid the foundation for national Orthodox Christian self-identity and philosophical thought.

Later, the view that the Russian lands are sacred would be encountered in various sources. And the legendary phrase "We are Russians - God is with us", which is attributed to the military commander Alexander Suvorov, became something of a national rallying cry.

The contents of the 'Book of the Dove' were orally handed down from generation to generation. In 1937, in his poem 'The Book of the Dove', Nikolai Zabolotsky wrote that he had known this "half-forgotten tale of our forefathers" from childhood. And that this "hallowed book" contained "the whole hallowed truth of the earth".

Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox