An art exhibition is under way in Paris. Pablo Picasso is not allowed in because he forgot to bring his invitation. ‘Prove that you’re Picassso,’ they tell him. The artist draws a dove of peace and is let in.

Then, Yekaterina Furtseva arrives at the same exhibition. She, too, has forgotten to bring her ticket and they are also not letting her in.

“But I am the USSR Minister of Culture,” she retorts indignantly.

“Prove it. Picasso proved he was Picasso!”

“And who’s Picasso?”

“Oh, it is you, Madam Minister, you can go in!”

That was one of the best-known jokes about Yekaterina Furtseva, who was often accused of ignorance, lack of education and taste and narrow-mindedness in cultural matters. It was thanks to her, however, that the first retrospective of Picasso was held at the Pushkin Museum in Moscow in 1956.

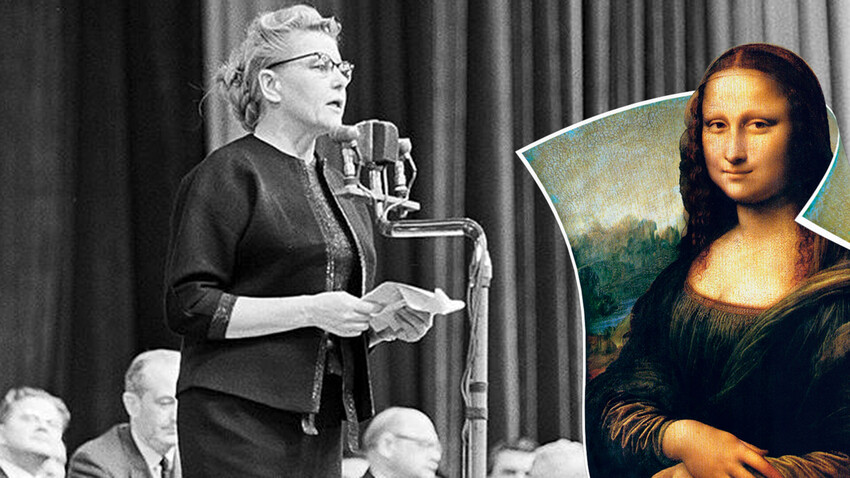

Furtseva at an art exhibition

Yury Abramochkin/SputnikYekaterina Furtseva (1910-1974) was Minister of Culture of the USSR for 14 years and went down in the country’s history as a somewhat controversial figure. On the one hand, she banned concerts by “harmful” capitalist rock bands like the Beatles and Rolling Stones, supported the campaign against Russian poet Boris Pasternak and subjected movies to endless censorship. On the other hand, she made arrangements for foreign movie stars, the La Scala opera company, French Impressionists and Leonardo da Vinci’s ‘Mona Lisa’ to come to the USSR.

As it happens, Furtseva was arguably second only to Khrushchev in the number of jokes that circulated about her, which certainly shows the scale of her personality. She was not, of course, very knowledgeable in matters of literature, music or art, but she valued professionals and heeded their advice in the most diverse fields. And she even personally rescued several movies and theatrical productions from censorship.

Culture Minister Yekaterina Furtseva

Pavel Manych/MAMM/MDF/russiainphoto.ruIf, at the dawn of the Soviet state, there were many women revolutionaries and the Bolsheviks prided themselves on having created gender equality, under Stalin and after him, women did not occupy particularly prominent positions in the USSR. So Furtseva’s dizzying career was more the exception than the rule. In the 1950s, she was one of the few women who managed to reach the top echelons of power - what is more, she remained one of the most influential people in the country for the next 20 years.

She had the ideal biography for a Soviet official: Born into a working-class family, she was a Komsomol activist and then became one of the organization’s leaders. During World War II, she helped with the evacuation of exhibits from Moscow museums. She joined the Communist Party early in life, played sports and, according to legend, when she was introduced to Stalin, he even paid her a compliment.

Furtseva and Khrushchev in 1963

Vladimir Musaelyan/TASSIn 1950 she was appointed deputy to Nikita Khrushchev, who was then head of the Moscow Committee of the Communist Party. At the age of 40, she essentially became second-in-command in Moscow.

In 1954-1957, Furtseva essentially became ‘Moscow boss’, heading the city’s Communist Party Committee in place of Khrushchev, who was, by then, in charge of the whole country. During her tenure, many now-iconic buildings and developments appeared in Moscow, including Luzhniki Stadium, the ‘Detsky Mir’ (‘Children’s World’) department store and the ‘Moskva’ bookstore on Tverskaya Street. And it was Furtseva who implemented the plan for the mass construction of affordable apartment buildings known as ‘Khrushchevki’.

Furtseva wanted to move up the party career ladder and even became a member of the Presidium of the Communist Party’s Central Committee. But, as a result of internal party intrigues and a clash with Khrushchev, she fell into disgrace and was not re-elected to the Presidium.

Kliment Voroshilov, Semyon Budyonny and Yekaterina Furtseva at the Moscow Kremlin

Pavel Manych/MAMM/MDF/russiainphoto.ruSo, she regarded her appointment to the post of Minister of Culture of the USSR in 1960 not as a success, but as a fall from grace, and… slit her wrists.

She managed to be rescued, however. After recovering, Furtseva took up her new responsibilities with the zeal of a former Komsomol activist and athlete.

It was Furtseva who was behind the idea of organizing the Moscow International Film Festival and the legendary 6th World Festival of Youth and Students. Both events brought an incredible number of foreigners to Moscow, totally transforming the old Soviet capital.

Argentine actress Lolita Torres and Yekaterina Furtseva (right)

Yevgeny Khaldei/MAMM/MDF/russiainphoto.ruFurtseva always paid a lot of attention to the theater - she was obsessed with the idea of setting up amateur drama theaters and believed this was the only kind Socialism needed and that professional ones had had their day. This was the subject of another joke about Furtseva. When she was insisting on amateur theaters for the umpteenth time, she was supposedly asked: “So, if you need medical assistance on a matter to do with women’s health, do you intend to see an amateur gynecologist?”

Left to right: Italian actress Gina Lollobrigida, Yuri Gagarin, actress Marisa Merlini and USSR Culture Minister Yekaterina Furtseva at a reception to mark the 2nd Moscow International Film Festival.

Yakov Khalip/SputnikUnder Furtseva, a multitude of theaters that have subsequently become cult venues were built and old ones renovated. They include the Teatr Estrady variety theater, the Taganka Theater and the new buildings of the Moscow Art Theater (MKhAT) and Sovremennik, as well as the Rossiya concert hall and the Bolshoi Circus on Vernadsky Prospekt (Avenue).

‘Izvestia’ news photographer Alexander Steshanov and USSR Culture Minister Yekaterina Furtseva at a reception after the International Tchaikovsky Competition.

Grigory Dubinsky/MAMM/MDF/russiainphoto.ruUnder Furtseva’s direction, a whole generation of 1960s poets emerged and flourished: Yevgeny Yevtushenko, Andrei Voznesensky, Robert Rozhdestvensky, Bella Akhmadulina among others. They were so popular that whole stadiums would be packed for their recitals.

Furtseva was also behind the idea of organizing foreign tours by the Bolshoi and Russian drama theaters, including to the U.S. In turn, La Scala and masterpieces from the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and other Western museums came to the USSR.

Furtseva (center) at an Henri Matisse exhibition in the Pushkin Museum

Emmanuil Yavzerikhin/MAMM/MDF/russiainphoto.ruFurtseva was considered ignorant in matters of art, but it was thanks to her that the first exhibitions of French Impressionists, artist Marc Chagall, trophy art masterpieces from the Dresden Gallery and treasures from the tomb of Tutankhamun were mounted in Russia. There was also the unprecedented exhibition of a single painting - Leonardo da Vinci’s ‘Mona Lisa’ (upon returning to Paris, it hasn’t left the Louvre since).

Irina Antonova, the long-serving director of the Pushkin Museum, recalled: “She had a passion for big projects. Shipping masterpieces from the Hermitage, the Tretyakov Gallery, the Russian Museum and the Pushkin Museum to Japan without insurance on her personal responsibility - she knew how to take risks…”

Furtseva had an impeccable sense of style: She invariably wore elegant dresses, snug-fitting outfits and smart shoes. Her hair was always perfectly coiffured.

Yekaterina Furtseva arrives at Heathrow Airport, London, UK, 1963

George Stroud/Daily Express/Hulton Archive/Getty ImagesAt the same time, she was a woman with an iron will, and no other female could easily have scaled such heights. She was a loyal “soldier” of the party and was just as fervent fighting against its “enemies”. The campaign against Boris Pasternak following the publication of ‘Doctor Zhivago’ in the West and his Nobel prize for literature is often held against her today. She also banned the cellist Mstislav Rostropovich from touring and performing, because of his support for the officially-vilified Solzhenitsyn - and the musician was forced to leave the USSR.

Another example is Furtseva’s ban on the war movie ‘Trial on the Road’ (1971) about a collaborator which was only finally released in 1986 and is now regarded as one of the best movies about the war. The reason was that it showed sympathy for people who gave themselves up and were taken prisoner. At the same time, it was said that Furtseva had a personal dislike of actor Rolan Bykov (who appeared in the movie). She also banned the children’s feature film ‘Attention, Turtle!’ (directed by Rolan Bykov) on the grounds of a perceived reference to the events in Czechoslovakia in 1968.

Yekaterina Furtseva and singer Leonid Utyosov on the latter’s 70th birthday

Pavel Manych/MAMM/MDF/russiainphoto.ruSinger Muslim Magomayev recalled: “She was an out-of-the ordinary person and had found her true calling. She loved her job, she loved performers. She helped many of them to make their name. But, for some reason, it’s now become almost a badge of honor to hurl nothing but opprobrium in her direction. I find it unseemly. Yes, she was part of the system, but, unlike many others, she operated inside it with a knowledge of the job she had been entrusted to do.”

Yekaterina Furtseva, poet Yevgeny Yevtushenko and sculptor Ernst Neizvestny

Alexander Ustnikov/Ninel Ustinova archive/russiainphoto.ruIn the 1970s, rumors started doing the rounds that she had alcohol problems. After a failed suicide attempt, she suffered from mental instability, believing that the party leadership did not value her. Additionally, not everything was going smoothly in her personal life - her husband was unfaithful to her.

She was ousted from the post of culture minister without warning over allegations of misappropriation of public funds relating to the construction of a dacha. This was an enormous blow to her and she died soon afterwards - her heart gave out.

Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox