“Shaking the world with my voice and grinning,

I pass you by, — handsome,

Twentytwoyearold.”

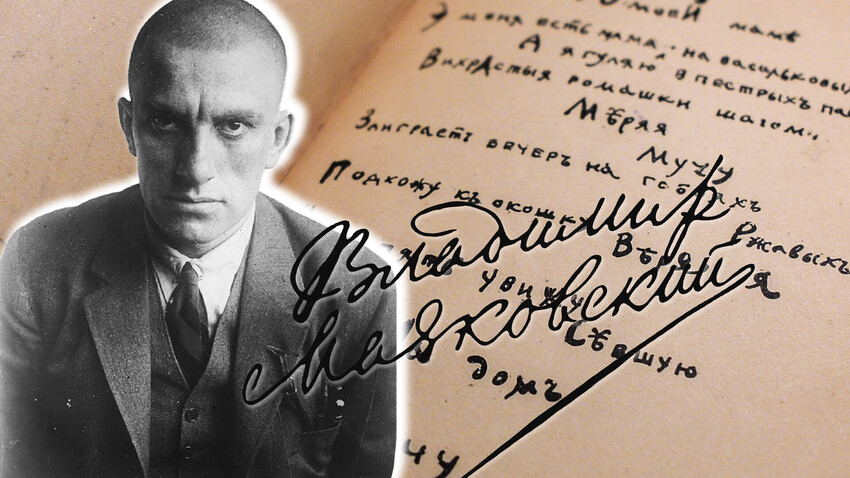

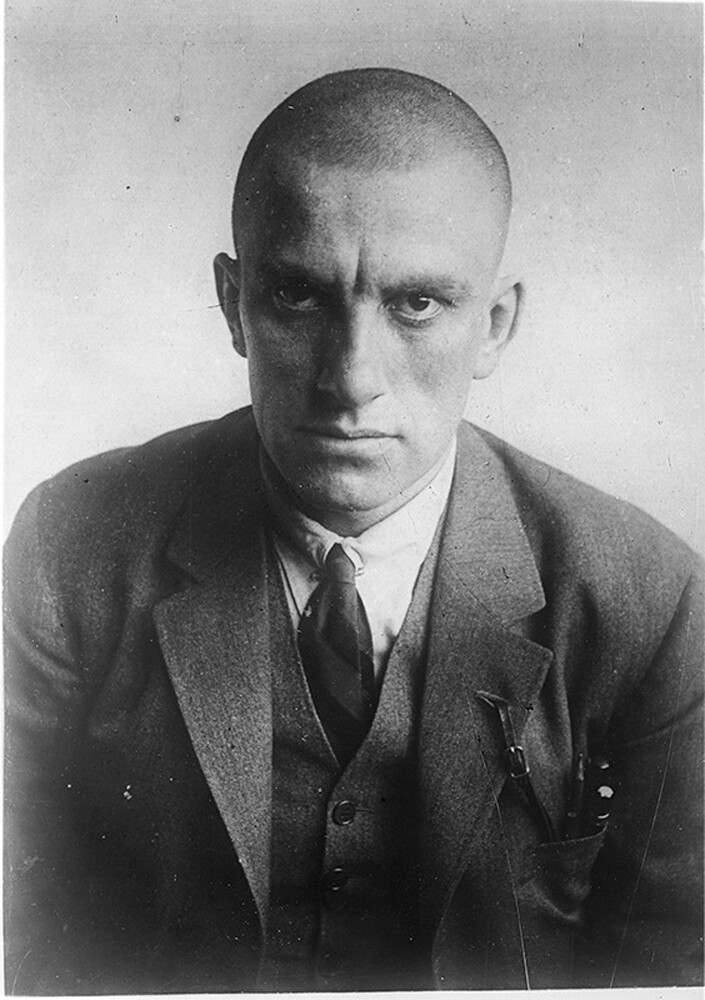

This is how Vladimir Mayakovsky (1893-1930), one of the most unusual, original and famous Russian poets, wrote about himself in his iconic early poem “A Cloud in Trousers” (1914).

He was tall, broad-shouldered, and stood out from the crowd. “He walked among people like Gulliver,” Russian author Kornei Chukovsky wrote. Mayakovsky thunderously read his poems with their jagged sharp rhythm. He seemed rude, but in fact, he was sentimental and fragile.

Vladimir Mayakovsky in 1924

Nikolai Petrov/SputnikMayakovsky is considered the main proletarian poet. He accepted the 1917 Revolution with enthusiasm, but in fact he joined the Bolsheviks back in 1908 and became fascinated by the ideas of communism.

“I, a latrine cleaner

and water carrier,

by the revolution

mobilized and drafted” (“At the Top of My voice”, 1930)

Mayakovsky made his debut in print in 1912. His poem was published as part of a Futurist collection with the scathing title “A Slap in the Face of Public Taste”. In its manifesto, the young innovative poets proposed to throw Pushkin, Dostoevsky, Tolstoy and other classics “overboard from the Ship of Modernity”.

Mayakovsky suggested to forget and cancel the old language and artistic tools. He positioned his poems in opposition to lacquered salon poetry. Not shy in expressions, he laughed at other poets, claiming that it was ridiculous to read Pushkin’s “disappointed lorgnette” to Donetsk miners and that it’s not appropriate to recite “Eugene Onegin” in front of the Labor Day parade.

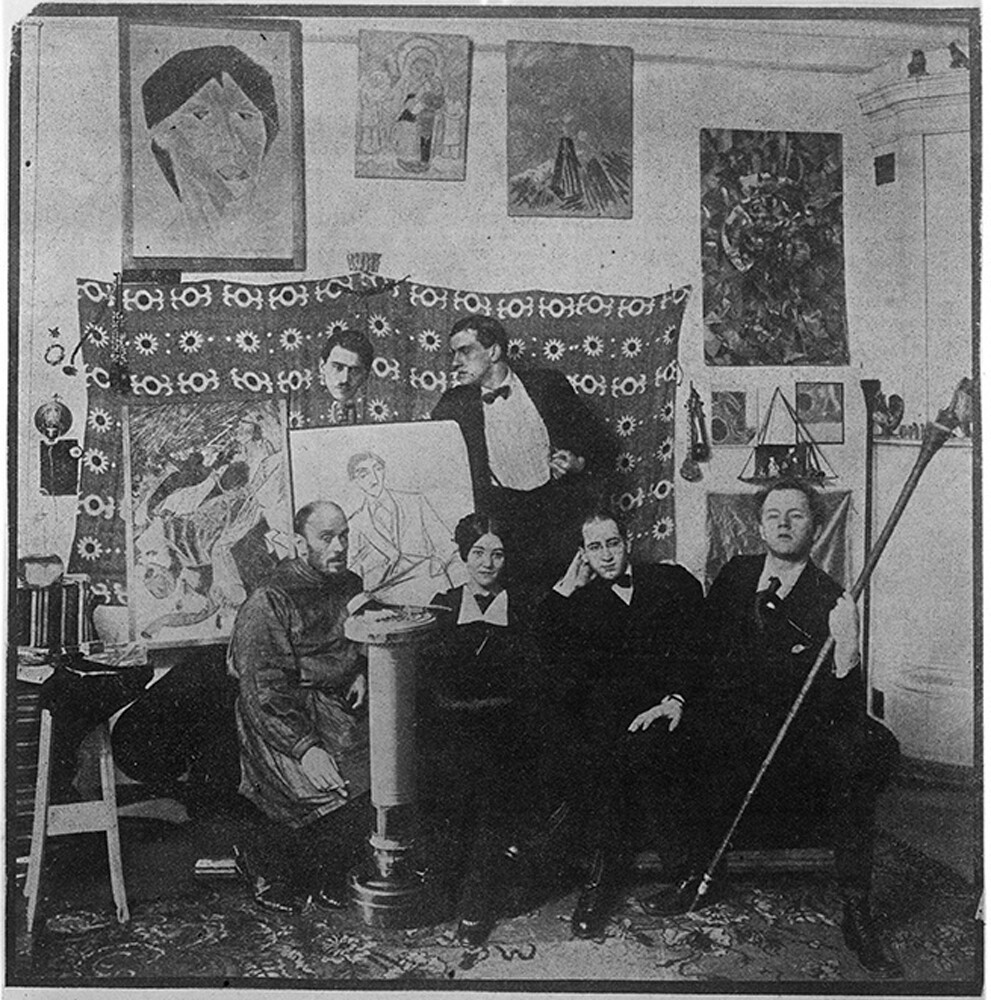

Mayakovsky and friends in the studio of avant-garde artist Nikolai Kulbin

State Museum of V.Mayakovsky/russiainphoto.ruInstead of the melodic old poetry he offered a shout; instead of a “lullaby” he suggested a “rattle of the drum”. He roared, shouting at the reader, comparing his words to weapons. They were his tools of agitation: “the armies of my pages”, “the pointed lances of the rhymes”.

Mayakovsky performed his poems in public and not in fashionable chamber salons. He spoke in front of large audiences, often consisting of students and even laborers.

“Mayakovsky’s speech is a loud, oral, public speech. Its natural field is the tribune, the stage, the square. But at the same time, it is an unceremonious speech, and it is this combination of familiarity and publicity that gives Mayakovsky's language its specificity and uniqueness,” wrote Grigory Vinokur, one of the first serious researchers of Mayakovsky.

One of his most famous poems, “But Could You?” (1913) is a challenge, where the lyrical hero boldly asserts himself and bullies his audience, questioning the use of deliberate hyperbole:

“But could you

now

perform a nocturne

Just playing on a drainpipe flute?”

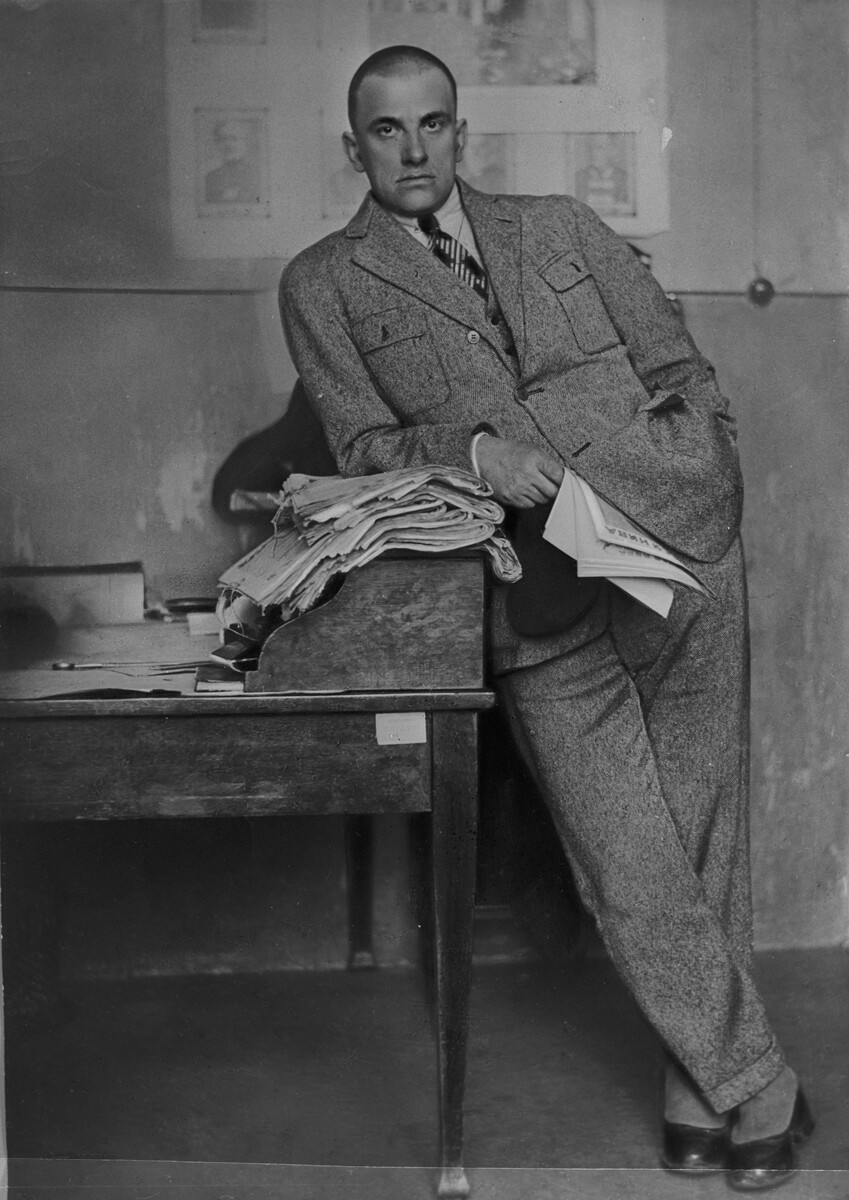

Vladimir Mayakovsky in 1914

State Museum of V.Mayakovsky/russiainphoto.ru“The Revolution, for instance, has thrown up on to the streets the unpolished speech of the masses, the slang of the suburbs has flowed along the downtown boulevards,” Mayakovsky writes in his essay “How are Verses Made” (1926). And it was necessary to speak with millions of such people in their own language. The poet introduced frank rudeness, often mixing it with neutral language. In addition to slang, he also introduced brand new words that he boldly invented himself.

While the new poetry did not fit into the old vocabulary, even more glaring was the fact that it also didn’t fit into the old verse structures. Starting with his earliest poems, Mayakovsky loved short, as if torn, lines; this became his trademark and one of the hallmark forms of his expressiveness.

Disregarding the traditional canons of poetry, he treated the lines frivolously. In the 1920s, his stepwise graphic ‘ladder’ poems appeared.

“When you’re writing a poem that's destined for publication, you must calculate how the printed text will be received as a printed text,” he explained. Each line should show the reader the author’s intonation, where to pause and what to emphasize.

Pictured L-R: Boris Pasternal, Sergei Eisenstein, O. Tretyakova, Lilya Brik and Vladimir Mayakovsky

Yury Levyant/SputnikMoreover, Mayakovsky overcomes the established syntax. “Our accepted system of punctuation, with full stops, commas, and question and exclamation marks is extremely poor”, he claims.

Sometimes it turned out that the usual grammatical connection between fragmentary pieces of his poems is simply absent; they are connected only by meaning, semantics, as Vinokur concluded.

Mayakovsky had studied at an art school, and the visual aspect of art and poetry was always very important to him. He was also greatly influenced by poet and painter David Burliuk, one of the founders of Russian Futurism and Cubo-Futurism.

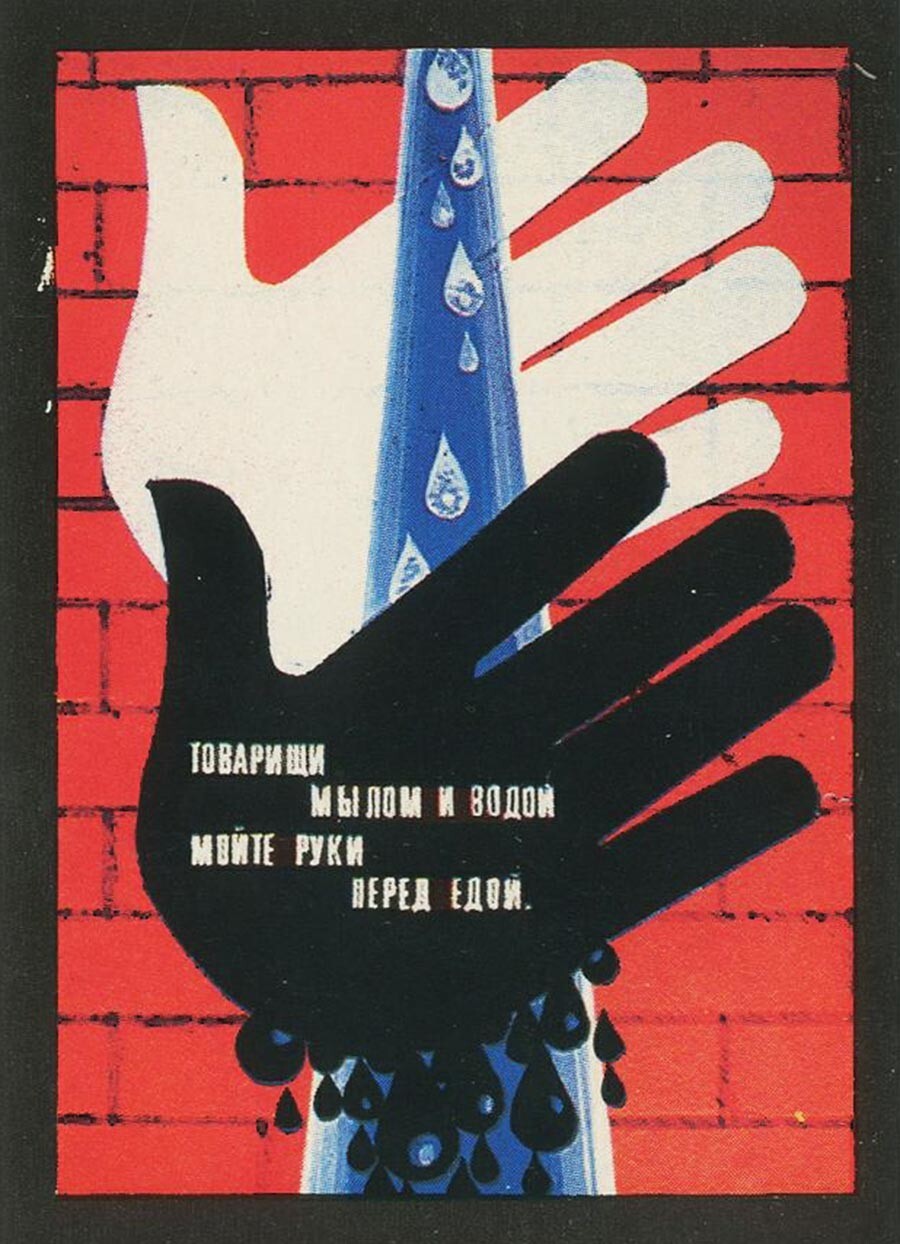

The themes of Mayakovsky’s poems were revolution, civil war, and communism (but also, love). For the first time, thanks to Mayakovsky, poetry began to serve the purpose of political agitation: Mayakovsky composed satirical slogans for posters published by ROSTA, the propagandistic Russian Telegraph Agency.

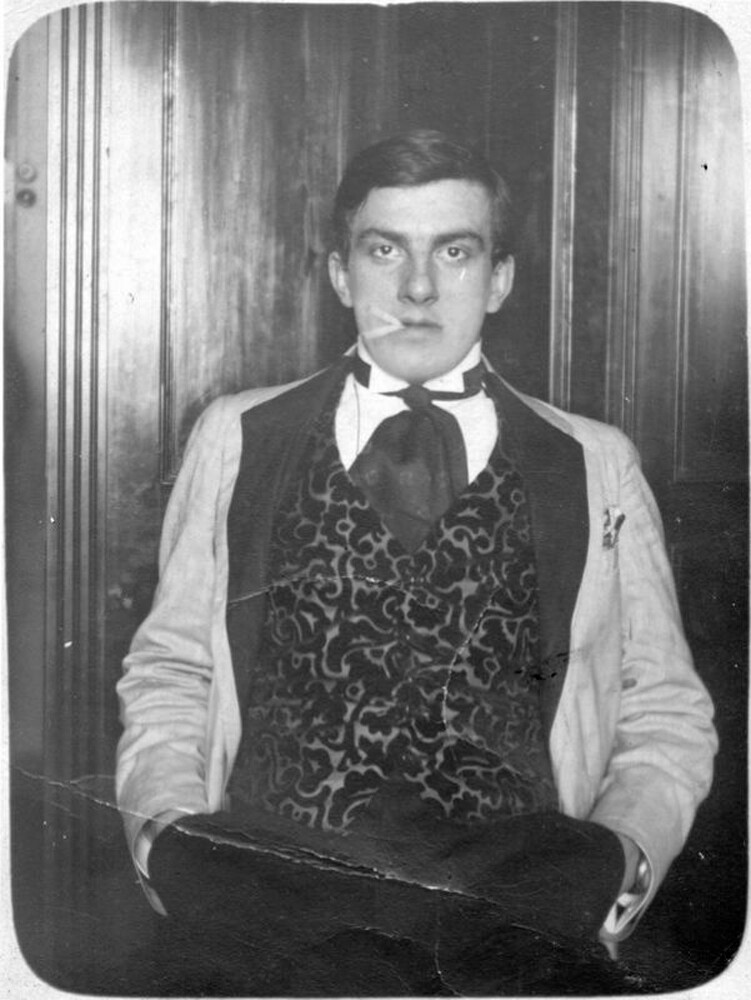

Vladimir Mayakovsky in 1924

State Museum of V.Mayakovsky/russiainphoto.ruUnder the nascent Soviet state, Mayakovsky’s success was meteoric. On November 7, 1918 – the first anniversary of the Revolution – Mayakovsky’s freshly-written socialist drama, “Mystery-Bouffe”, premiered on the stage of the Theatre of Musical Drama in Moscow. It was staged by the leading director Vsevolod Meyerhold, with stage decorations designed by avant-garde artist Kazimir Malevich.

The new socialist man had to be educated, and so Mayakovsky didn’t disdain “lowly” themes, such as hygiene. In the 19th century such types of poetry were simply unimaginable.

“Comrades,

with soap and water,

wash your hands

before you eat!”

Mayakovsky also wrote poems for children. One of the most famous is “What is good and what is bad” (1925), a kind of behavioral manifesto for the children of communism.

“If his eyes to books are glued,

If he’s never shirking,

Then the boy is very good,

For he’s fond of working.”

The civic poetry, patriotic verses about love to the Motherland, also got a new semantic and aesthetic content. In one of his best known works, “My Soviet passport” (1929) Mayakovsky writes:

“I pull it

from the pants

where my documents are:

read it

envy me —

I'm a citizen

of the USSR!”

Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox