Today the Northern Sea Route (NSR) is a transport artery. It is actively used by Russia to serve its Northern and Far Eastern territories, as well as for shipping goods to and from China, for example. This provides a massive commercial advantage, since a voyage from St. Petersburg to Shanghai along the Northern Sea Route takes only 28 days, compared to the 50 days it takes to go via the Suez Canal.

However, even today, navigating the Arctic Ocean is almost impossible without a specialized fleet that can negotiate ice floes and cut a path for ships, should they find themselves trapped in ice.

Welcome to the Arctic, where the ice stands three meters tall for nine months in a year, temperatures reach minus 50 C , winds rage at speeds of up to 50 m/s and, and in winter, the night never ends. Despite the deadly danger of navigating in such conditions, many countries sought to master the sea route in order to discover the quickest way from Europe to Siberia and the Far East, and then from the Atlantic to the Pacific.

Thus, in the mid-16th century, the crew of the British ship ‘Edward Bonaventure’, under the command of Richard Chancellor, disembarked not far from today's Severodvinsk. The vessel was sent by the London-based Muscovy Company to find the Northeast Passage to China. The route was of interest to the British and their neighbors not only because of China, however. The Europeans knew that the best furs, which the Russians traded with Europe, first via Kholmogory and later Arkhangelsk (about 1,200 km north of Moscow), came from Siberia, and sought to establish their own contacts and trade links with the Siberian town of Mangazeya.

The Pomors, who lived in the Russian North, had been the first to open up sections of the Northern Sea Route. They traded with foreign merchants and were accomplished navigators in the Northern seas. They were the first to establish trade with Siberia, and this was how the center of Siberian trade, Mangazeya, had emerged. All the riches found in the Siberian forests flowed there, and from there, they were sent by sea to Arkhangelsk and then to the rest of Russia, or Europe.

Foreign activity in the region was so widespread that the Russian Tsar had to prohibit Russian and foreign merchants from using the Northern Sea Route on pain of death.

Based on the Pomors' experience, Russian diplomat Dmitry Gerasimov drew up the first plan for a sea route from Europe to China through the Arctic Ocean in the 16th century. He told Italian historian Paolo Giovio about the plan, and the latter shortly afterwards published Gerasimov's project. The idea quickly caught on both in European countries and in Russia, but there were no technical capabilities for sailing in the Arctic at the time. And the idea of a through route across the Arctic Ocean had to be abandoned until the 19th century.

It was only at the end of the 1870s that the Swedish vessel ‘Vega’ made the first through navigation. In the wake of this expedition, in 1893, the Norwegians sailed through the Arctic Ocean. In third place, in 1900-1902, were Russian explorers on the schooner ‘Zarya’. And, although the Russians were not the trailblazers, the Soviet Union was later the first to demonstrate the possibility of effective use of the Northern Sea Route and winter navigation.

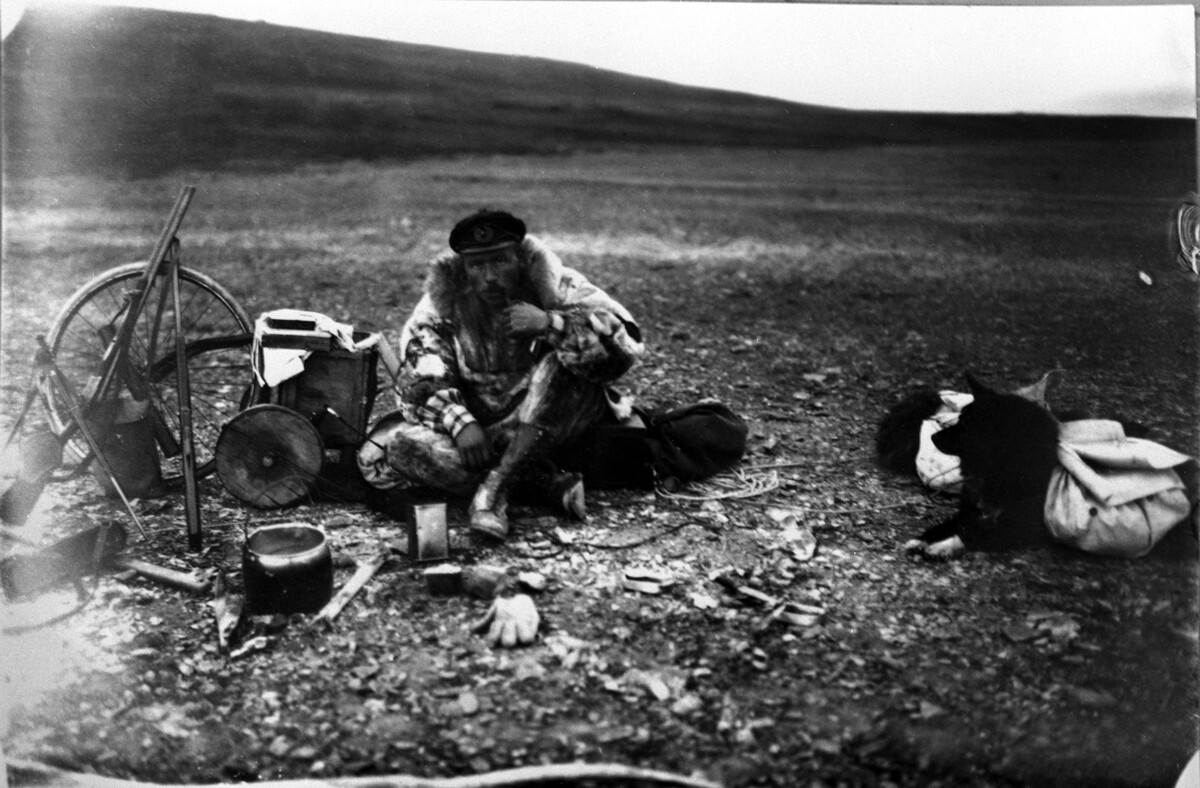

The crew of schooner ‘Zarya’.

Public DomainA new stage in the development of the Arctic ensued with the assimilation of the islands of the Arctic Ocean. An expedition commanded by Georgy Ushakov landed on Wrangel Island in 1926, and a settlement and polar station were established there. In 1929, the reclamation of Franz Josef Land had begun. Both these territories now belong to Russia. After another few years, in 1933, the USSR was the first country to carry out a winter voyage in the Arctic when an expedition brought cargo to the settlers on Novaya Zemlya.

Georgy Ushakov in 1930.

SputnikIn the early 1930s, thanks to the dynamic efforts of the researchers of the 1920s, the conditions arose for the full development of the Northern Sea Route. Expeditions were regularly mounted in its western sector: a network of radio communication stations was installed at key coastal locations, and meteorological and ice forecasts were already being compiled for the Barents and Kara seas. A breakthrough came in 1932 when an expedition commanded by Otto Shmidt on the icebreaker ‘Alexander Sibiryakov’ traversed the whole of the Northern Sea Route from Arkhangelsk to Vladivostok in a single sailing. Several breakdowns occurred on board during the expedition, and the steamship even lost its propeller screw. The researchers made a set of improvised sails and reached their intended destination. The total duration of the voyage was two months and three days.

The icebreaker ‘Alexander Sibiryakov’, 1933.

Mark Troyanovsky/МАММ/МДФ/Russia in photoSailing in the impassable ice of the Arctic remained a very difficult and dangerous undertaking, however. In 1933, in the wake of the triumph of the crew of the ‘Alexander Sibiryakov’, the steamship ‘Chelyuskin’ set out into Arctic waters. In the Chukchi Sea it was crushed by ice and drifted along with its entire crew for almost five months before sinking. The passengers managed to evacuate the vessel and spent two months on an ice floe in the midst of the Arctic winter waiting for rescuers to arrive. Fortunately, everyone got back to shore. In mid-century shipping became safer – in 1953 the USSR began building nuclear-powered icebreakers, with the help of which year-round navigation subsequently became possible.

The steamship ‘Chelyuskin’.

SputnikThe first nuclear-powered icebreaker ‘Lenin’, came into service in 1959. Thanks to the creation of the nuclear-powered fleet, voyages became faster and more regular. The time it took to cover the route went down to 18 days. The number of ports, polar stations and observatories in the Arctic grew.

In 1977, the second nuclear-powered icebreaker in history, the ‘Arktika’, became the first surface vessel to reach the North Pole.

The crew of the first nuclear-powered icebreaker, ‘Lenin’ skiing in front of it, 1960.

Evgeny Haldey/SputnikIn the 1980s cargo traffic reached peak levels – it took until 2016 to exceed the performance indicators of those years.

The Northern Sea Route allowed the Soviet Union to actively develop the Arctic and turn it into an important economic zone: oil and gas reserves were discovered there, and a multitude of ports and industrial towns established. But the main outcome was that a new and rapid transport link to the Far East and the states of the Asia-Pacific region was opened up.

White bears on drifting ice station 'North Pole-19', 1970.

Roman Denisov/SputnikThe development of the Northern Sea Route slowed down sharply as a result of the economic crisis that erupted after the collapse of the USSR in 1991. But, since 2006, thanks to projects by the government and large corporations, the volume of shipments has started to grow by leaps and bounds. The development of the Northern Sea Route has now been recognized as a strategic priority, and the government has adopted a plan for the development of the transport artery up to the year 2035.

According to Vyacheslav Ruksha, deputy director-general of the State Atomic Energy Corporation Rosatom and head of the Directorate for the Northern Sea Route, the coronavirus pandemic and international situation have made it necessary to adjust plans for the development of the Northern Sea Route, but the transport artery is still functioning effectively and building up cargo traffic. "The principal task of the Northern Sea Route today is to support the country's national interests. Russian companies are supplying an adequate flow of cargoes, sending liquefied natural gas and oil via the Northern Sea Route. The 2024 performance targets might be reached later than planned, and some projects have been pushed back by a year. But, I think the 2030 performance target of 150 million tons of cargo traffic will even be exceeded," he says. For reference, the Northern Sea Route's cargo traffic in 2022 was 34.1 million tons, while annual cargo traffic along the Suez Canal is around 1.4 billion tons.

Yamal LNG.

NovatekThe Asia-Pacific region countries located in the Northern Hemisphere are interested in the Northern Sea Route. For them, the shipping of goods via the Northern Sea Route is often economically preferable to the southern route via the Suez Canal. For example, a shipment of cargo from St. Petersburg to Shanghai along the route will take just 28 days, while sailing through the Suez Canal would require around 50 days. China is showing particular interest in the Northern Sea Route – starting this year, the Chinese company ‘Hainan Yangpu NewNew Shipping’ will be supplying five ships for a regular container service during the summer and autumn navigation season.

But the Northern Sea Route is not seen by experts as an alternative to the Suez Canal: "The Northern Sea Route opens up additional logistical options for the countries of Northern and Eastern Europe and certain countries of the Asia-Pacific region. The Suez Canal has completely different user-countries, and we can only attract around 10 percent of cargo traffic from there – i.e. around 100 million tons," Ruksha explains. Arab countries are also interested in the Northern Sea Route as investors.

Another important task is to maintain year-round navigation in the eastern sector of the Northern Sea Route. The first steps will be taken as early as 2024 when Arc7 enhanced ice-class ships will start regular shipments of Russian cargoes to Asian markets. Currently, there is only year-round navigation in the western part of the Northern Sea Route.

The nuclear-powered icebreaker 'Yamal', 2015.

Valery Melnikov/SputnikDear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox