Why was bodybuilding outlawed in the USSR? (PHOTOS)

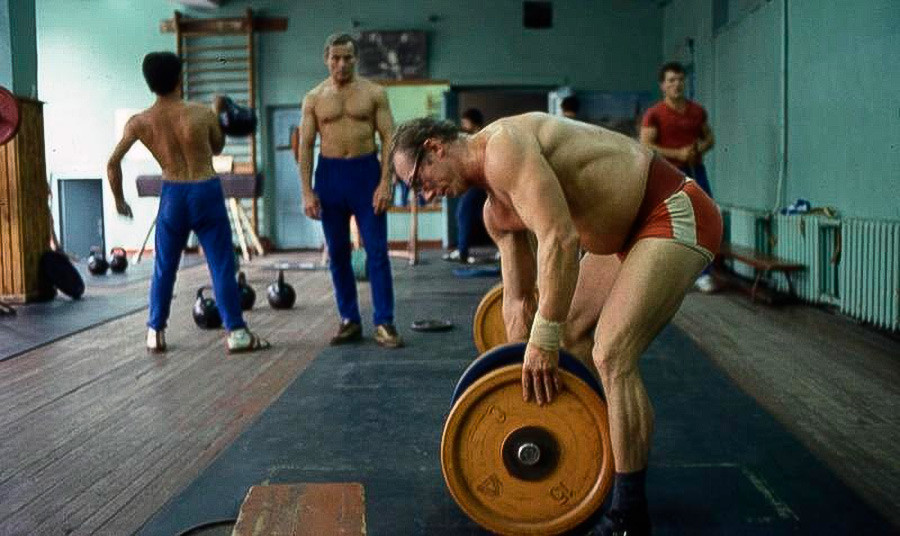

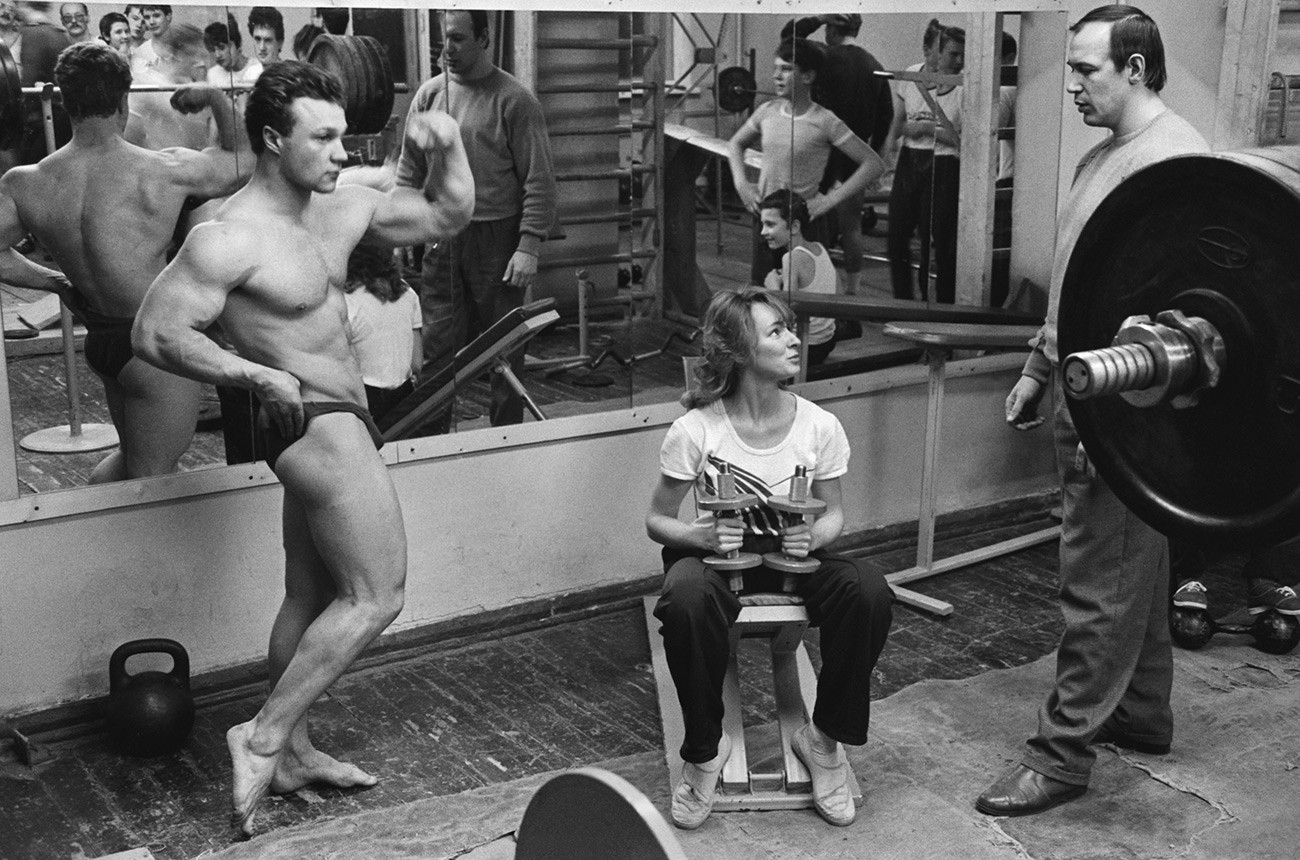

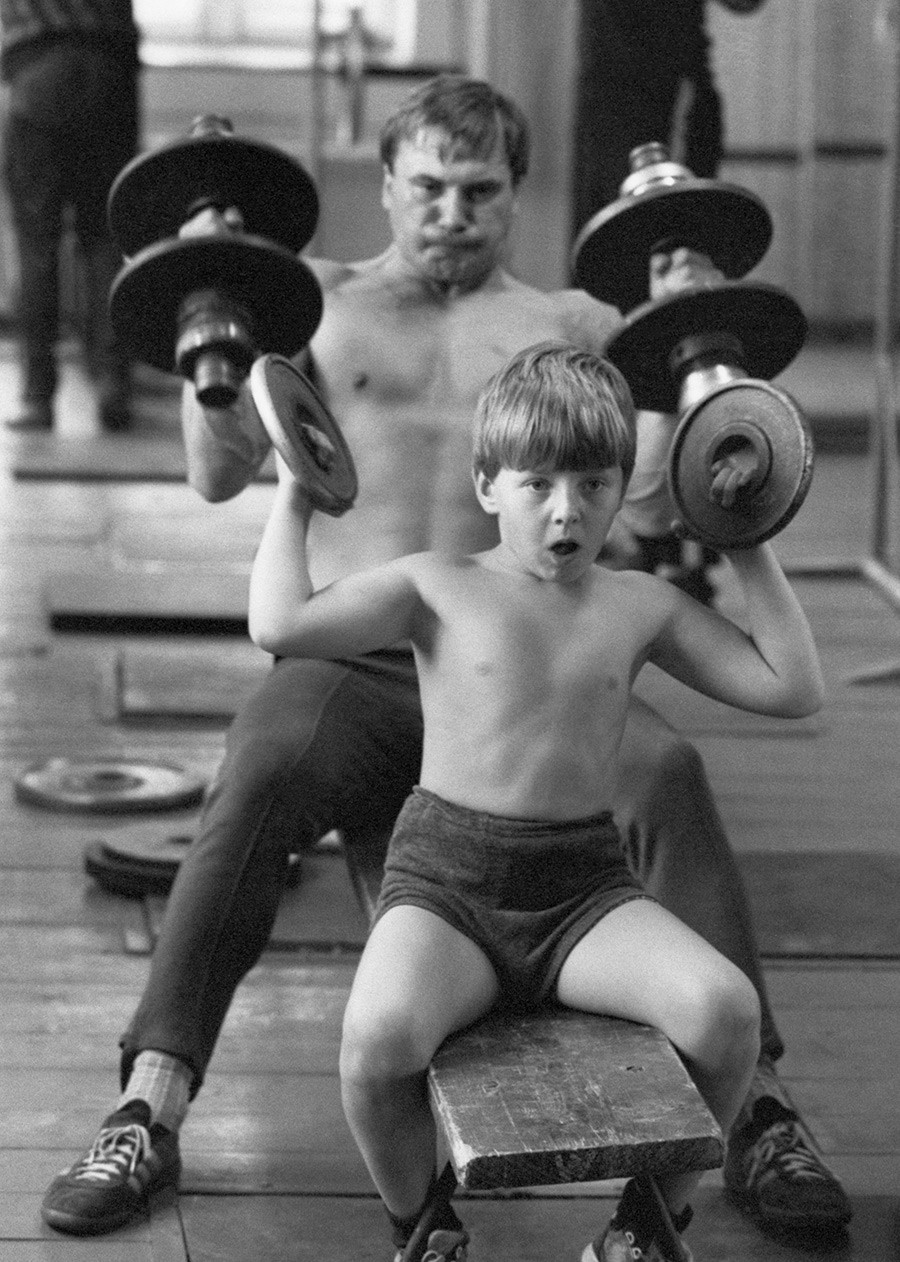

Probably no other athletes suffered as much in the Soviet Union as bodybuilders. They had to train in the basements of residential buildings, lift pieces of rail track instead of normal weights, and have dumbbells made for them illegally at factories in exchange for things like vodka. Indeed, growing one's muscles in a country with a communist ideology was not easy – bodybuilding and communism did not go well together.

It all began in the 1960s, when cinemas across the Soviet Union were screening the Spanish-Italian film Hercules, where the title role was played by Steve Reeves. By today's standards, his physique would not cause a sensation in the bodybuilding world, but for people in the USSR it was impressive. Hercules was seen by 36 million people and it spurred many men to get in shape.

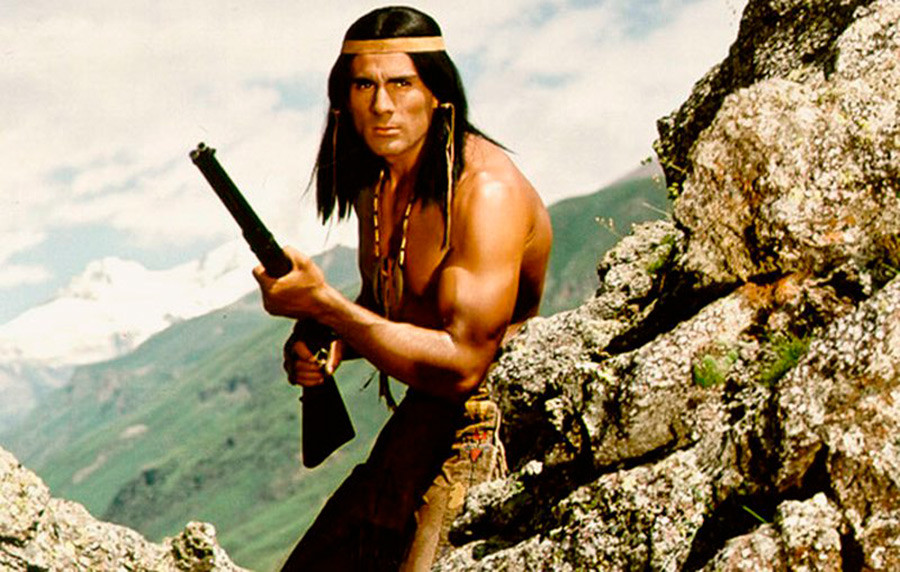

A year later Soviet bodybuilders were blessed with new icon in Gojko Mitic, a Yugoslav actor and gymnast who rose to fame as a noble Red Indian in films produced in the GDR. In the late 70s and early 80s, everyone wanted to be like Gojko. And even a state ban on his films didn’t change this.

Bodybuilding was outlawed in the USSR for ideological reasons. "Bodybuilding? Pumping up muscles and posing in front of a mirror? What does a Soviet person want with this – admiring one's reflection?" one official said at a session of the State Sports Committee [the Soviet Ministry of Sport] in the spring of 1973. Pumping up muscles simply for the sake of looking good was considered an anti-Soviet occupation. Bodybuilding was officially banned.

The only “legal” strongmen were circus performers. One of them was trapeze artist Alexander Shirai, who from the 1950s modelled for sculptures and paintings depicting workers, miners, and athletes.

Everyone else had to work out in the shadows. "Back then, they were basements of apartment blocks that we cleaned out ourselves and turned into weight rooms," recalls bodybuilder Alexander Sidorkin.

It was, of course, impossible just take over a basement. Apartment blocks were always under the supervision of a housing organization or some other authority. These bodies were actually pretty tolerant of bodybuilders, but the same could not be said for the police and Komsomol members, who from time to time organized raids against bodybuilders.

Weights and dumbbells were expensive and hard to get because you could not buy them in a shop. Another problem was nutrition. "We would go to the central children's department store in Moscow, to the baby food section to buy “Malysh” or “Malyutka” instant formulas. Malysh had fats in it, so it was for those who wanted to gain weight, while Malyutka had protein, for those who wanted to slim up a bit," Sidorkin recalls.

Sidorkin says there was a nearby state farm where pigs were always fed with soy protein: "So we would bring 25-kilo bags of soy protein to our weight room and mix it with water. Of course, it had a foul taste and it would not mix property. We still we drank it, and it was ok, we grew [muscles] and it was fine."

Cutting, bulking up, nutrition – many Soviet bodybuilders learned about these processes from a rehabilitated prisoner, Alexander Solzhenitsyn's cellmate in the Gulag, Georgi Tenno. In 1968, his book “Athleticism” was published, which for many years became Soviet bodybuilders’ “Bible.” Tenno knew English well and read foreign literature on the subject.

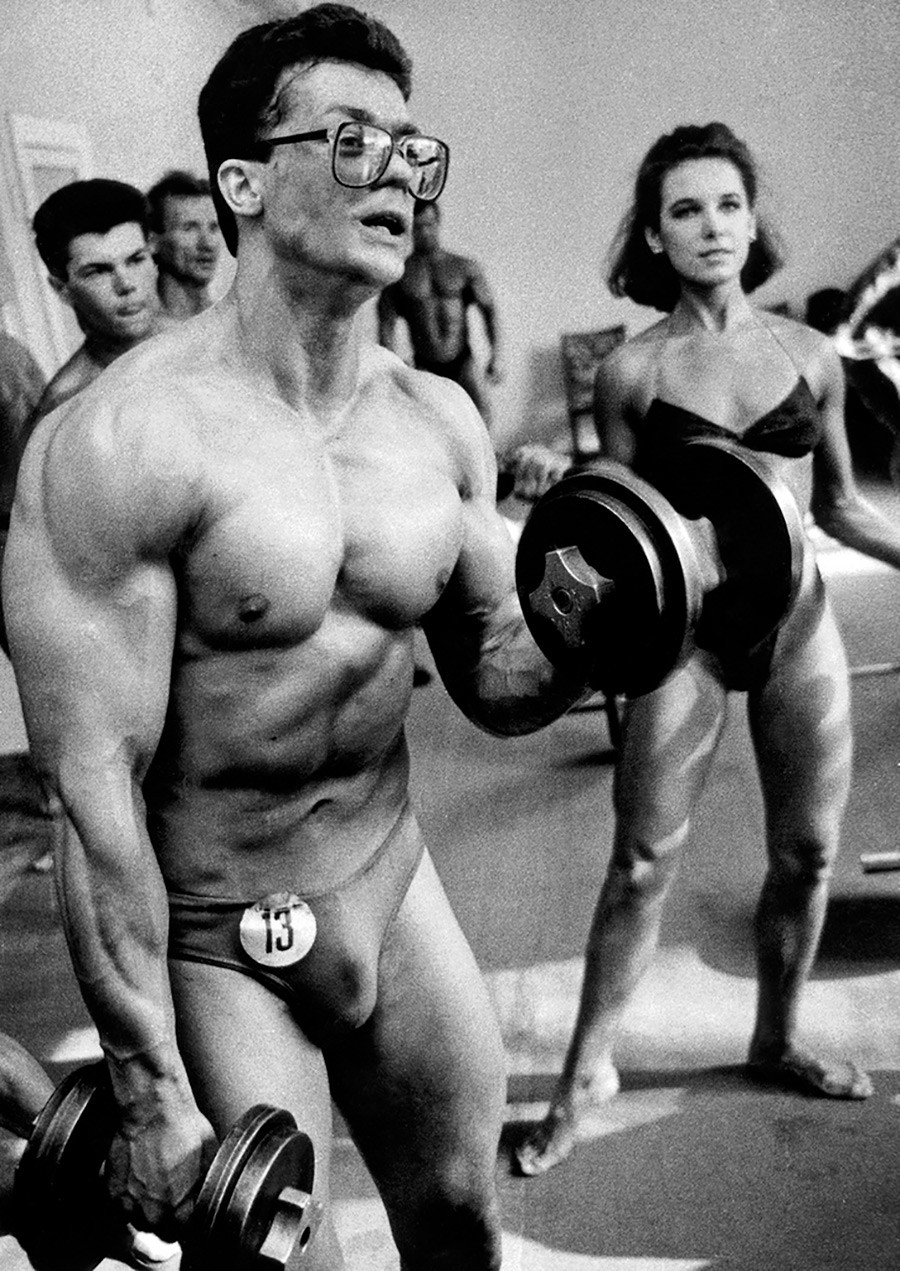

The ban on bodybuilding was lifted during the perestroika years, starting from 1987. Then the USSR began holding official bodybuilding championships and Soviet bodybuilders started looking up to new heroes: Arnold Schwarzenegger, Bruce Lee, and Sylvester Stallone.

Yet, along with this freedom, Russian bodybuilders also precured steroids, pharmaceuticals, and deadly injections of synthoy from the West. This guy is living proof that the practises still go on.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox