Why did a female Nazi executioner live in the USSR without hiding?

“It was my job,” Antonina Makarova calmly told the KGB investigator in detailing how she machine-gunned Soviet citizens during WWII. According to various sources, the kill list of this female executioner, one of the most brutal in history, ranged from 168 to 1,500 people.

Makarova, better known as Tonya the Machine-Gun Girl, was not always a killer. Before collaborating with the Nazis, she did the exact opposite — working as a nurse in the Red Army, volunteering for frontline service.

But her stint there did not last long. In the fall of 1941, around 600,000 Soviet soldiers were surrounded in the “Vyazma cauldron,” and among them was the 21-year-old Antonina.

After a miraculous escape, Makarova wandered for months through forests and villages, finding temporary shelter with locals, but always moving on. Then in the summer of 1942, she entered the village of Lokot in the German-occupied Bryansk region.

“A place under the occupying sun”

The region where Makarova found herself was fundamentally different from others under Nazi occupation. As an experiment, the semi-autonomous Lokot Autonomy had been set up under the local “burgomaster” Konstantin Voskoboinik (replaced by Bronislav Kaminsky after being killed by partisans in January 1942). All the same, to “maintain order,” the region was under German supervision, and units of the 102nd Hungarian Infantry Division were stationed in populated areas.

The Autonomy was allowed to create its own defensive units, which later morphed into the so-called Russian National Liberation Army (RONA). It was this unit which, in the summer and fall of 1944, gained notoriety for extreme brutality during the Warsaw uprising, literally drowning the city in blood.

Bronislav Kaminsky surrounded by German and RONA officers.

BundesarchivHiding in the home of one villager, Antonina Makarova pondered her next move. She knew that a large partisan detachment was active in the nearby forest. However, after seeing the relatively luxury in which the Russian collaborators lived, Makarova decided (according to special services historian Oleg Khlobustov) “to seek out a warm place under the new occupying sun.”

Makarova ingratiated herself with the Germans and the “self-governing” Russians by openly engaging in prostitution and attending rowdy parties. Soon, Antonina became involved in more serious matters — namely, the execution of Jews, partisans, and local opponents of the new government.

Many years later, Makarova would inform her KGB investigators that no one had forced her to do it: “They plied me with vodka, and I carried out my first execution when drunk.” Thus, Tonya the Machine-Gun Girl was born.

Virtuoso executioner

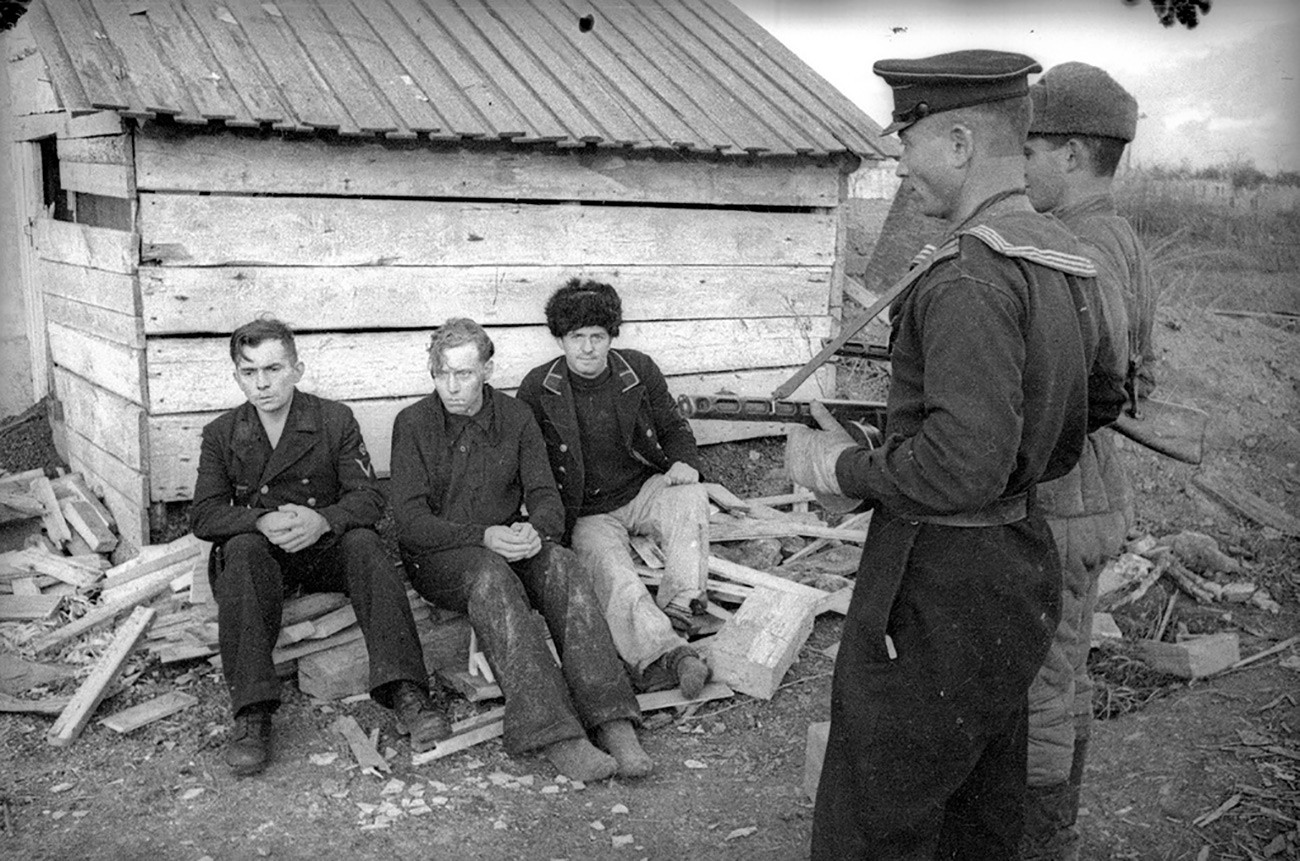

The executions took place in a ravine near a former stud farm, which the Nazis had turned into a prison. Makarova lived in the same building. From time to time, locals would see the gates of the prison open and a group of captives file out followed by a cart carrying a machine gun and behind it a young woman nonchalantly chewing a piece of straw.

“I didn’t know the people I shot. And they didn’t know me. So I felt no shame before them... For me, all those sentenced to death were the same. Only their number changed... The arrested were lined up facing the pit. One of the men rolled my machine gun to the execution site. At the command of my superiors, I knelt down and fired until everyone fell dead,” Makarova told the KGB investigators.

“Her executions were like a ghoulish theatrical performance. The leaders of the Lokot Autonomy came to watch, and German and Hungarian generals and officers were invited,” says historian Dmitry Zhukov.

Tonya rarely missed, and anyone she didn’t hit, she finished off with a pistol. Once, several children survived, the bullets flying over their heads. Playing dead, they were later saved by locals who had come to bury the victims. The children were taken to the partisans in the forest, who vowed to hunt the woman executioner down.

Makarov removed clothing and personal items from the dead, lamenting that they were spoiled by blood and bullet holes.

The search begins

In the summer of 1943, Tonya sensed that the tide was turning against her Nazi patrons. The resurgent Red Army was taking back Soviet territory from the Germans.

Makarova went to Bryansk to get treatment for syphilis, never to return to Lokot. Her trail suddenly went cold.

The Soviet military counterintelligence service, SMERSH, opened an investigation into Tonya immediately after the liberation of the Bryansk region. In the ravine near the Lokot prison, the remains of 1,500 people were uncovered.

But despite the efforts of the local population, interrogations of captured collaborators, and examinations of numerous documents, nothing could be gleaned about Makarova’s birth or relatives.

Lucky breakthrough

For years after the war, Tonya’s case file passed through the hands of successive KGB investigators to no avail. That changed in 1976, when the case file of an officer by the name of Panfilov landed on the desk of the authorities for a routine check prior to a foreign mission. It indicated that Panfilov had a sister, Antonina, who went by the surname Makarova.

It transpired that back in her school days Antonina had been too shy to say her last name out loud, so her classmates had mistakenly told her teacher that it was Makarova (after her father’s first name Makar). Documents were issued in this name, despite the fact that she was listed as Panfilova at the birth records office.

This explained why, among the 250 Antonina Makarovas found and checked by the KGB, the wanted Tonya the Machine-Gun Girl was strangely absent. For the search had covered only those registered under this name at birth.

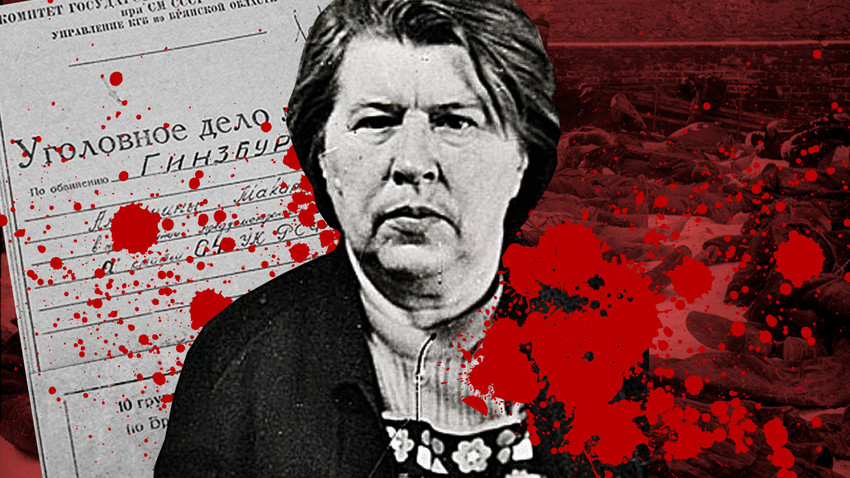

Respected war veteran

Panfilov’s sister, Antonina Makarova, now worked at a garment factory in the city of Lepel, Belarus. The wife of a war hero, Sergeant Victor Ginzburg, she too was a respected veteran, decorated with numerous awards and giving talks to young people.

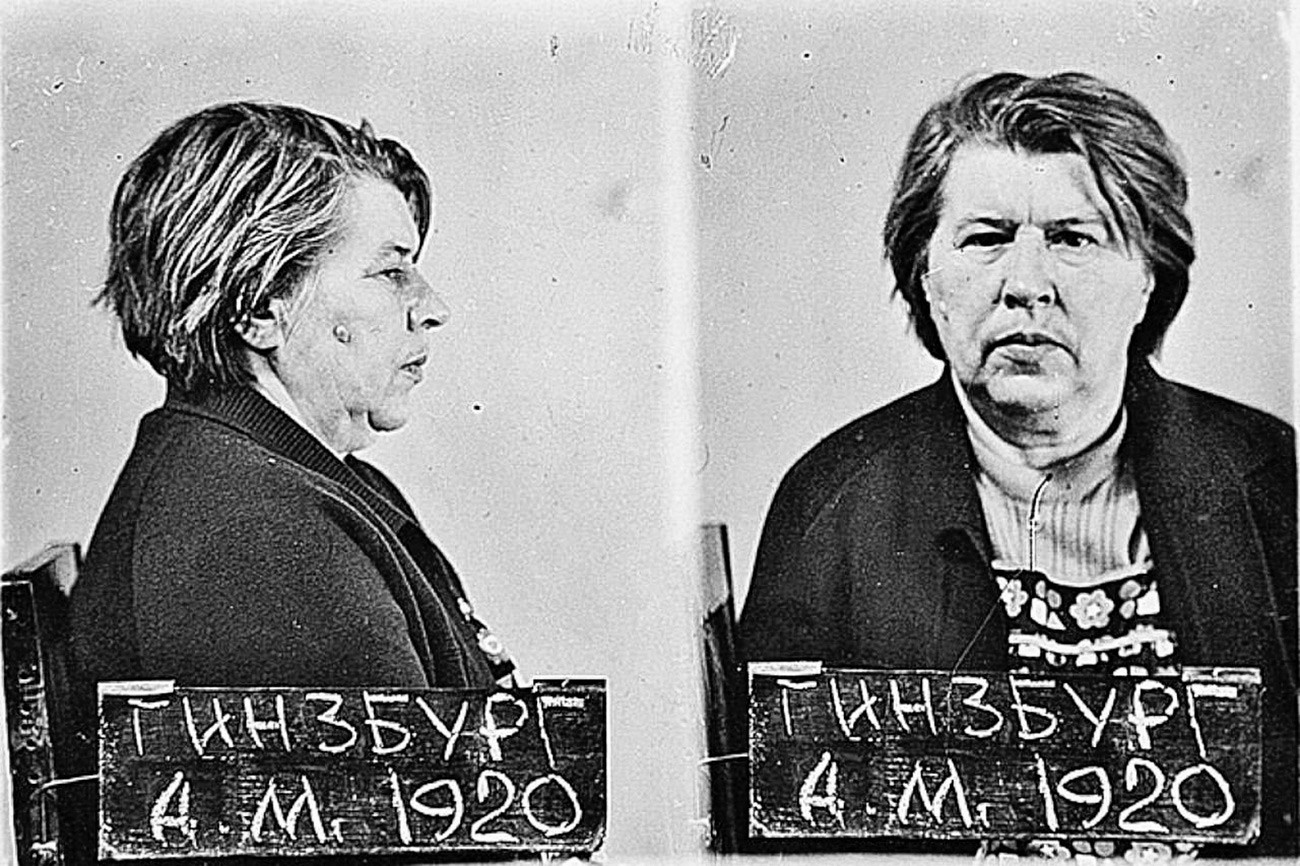

Makarova (far right, seated) in police lineup.

FSB archive of the Bryansk regionKnowing the risk of wrongly slandering a war veteran, the KGB carefully watched Makarova for a whole year. The investigators brought people to Lepel who knew and could identify that very same Tonya the Machine-Gun Girl. Among them were former lovers and collaborators who had returned home after serving time in the Gulag.

In the end, they confirmed that the venerable war veteran Antonina Ginzburg was indeed none other than the elusive Tonya the Machine-Gun Girl, whose relatives, including husband and two daughters, suspected nothing of her crimes. Makarova was immediately arrested.

It turned out that, during the mass retreat of the German army, she had ended up in Konigsberg (later renamed Kaliningrad). When the Red Army captured the city, Antonina reverted to being a nurse and got a job in a hospital. There she met her future husband, and took his surname.

Execution

Throughout her interrogation, Antonina Panfilova-Makarova-Ginzburg remained perfect calm. She was sure that her actions were all attributable to the war, sincerely believing that, given the lapse of time, she would get off with a few years in jail and soon be released.

However, the court decided otherwise. It was not possible to prove her complicity in the murder of 1,500 souls, but it was established beyond doubt that the deaths of 168 of those executed at Lokot lay on her conscience.

At 6am on Aug. 11, 1979, Antonina Makarova received a taste of her own medicine — execution by firing squad, whereupon the KGB finally closed the book on one of the longest cases in its history.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox