“In those days, to be declared a beauty in front of everyone was shameful! But it was nothing like the competitions that are held nowadays,” recalled Marina Chaliapina.

In 1931, the daughter of the great Russian opera singer Feodor Chaliapin won the Miss Russia crown among Russian émigrés in Paris. Her magnetism made a lasting impression on all who met her, but she is remembered chiefly for her extraordinary career path, which included time as a naval officer.

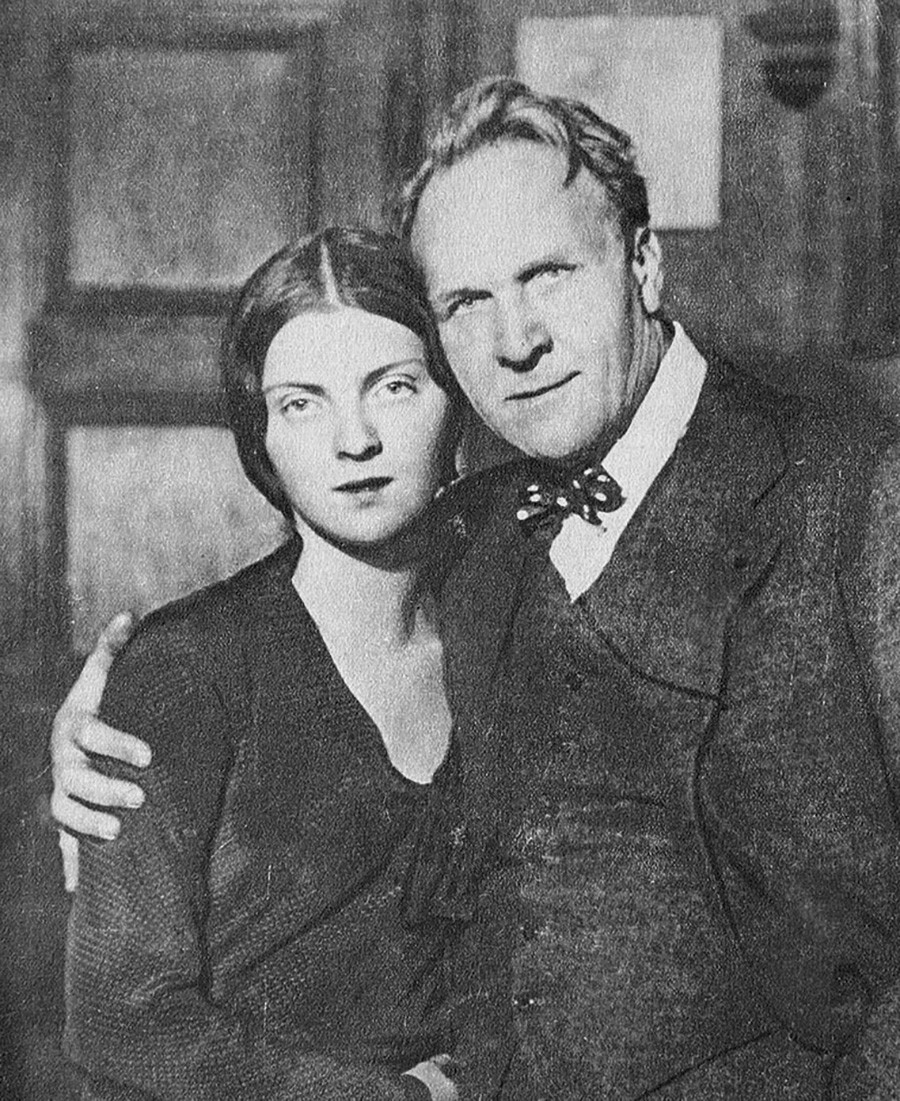

Marina Chaliapina was the daughter of Chaliapin and Maria Petsold, his mistress, who later became his wife. They were forced to emigrate from Russia soon after the revolution, which turned the family’s fortunes upside down: Chaliapin’s property and savings were confiscated, and only the intervention of writer Maxim Gorky afforded some breathing space, allowing him to work for a spell as the artistic director of the Mariinsky (formerly Imperial) Theater, and even become the first recipient of the title People’s Artist of the Soviet Union. However, the family still struggled to put food on the table, and Marina was diagnosed with a severe form of tuberculosis.

Feodor Chaliapin and Maria Petsold

Museum A.M. Gorky and F.I. Chaliapin, KazanIn 1921, with the help of friends, the young girl was taken to Finland for treatment, and Chaliapin himself received permission to tour abroad. Having had the foresight to buy a property in Paris, he soon moved Petsold there, together with her children and almost all of his from his first marriage. Marina, now recovered, also relocated to the French capital.

Boris Kustodiev. Portrait of Martha and Marina Chaliapin, 1920.

Yekaterinburg Museum of Fine ArtsBy then, many Russian aristocrats had emigrated, among them prima ballerina Matilda Kshesinskaya, who was hounded by scandalous rumors of a connection with Nicholas II. The nine-year-old Marina was sent to her ballet studio.

F. I. Shalyapin with his daughter Marina.

Museum A.M. Gorky and F.I. Chaliapin, Kazan“I was desperate to become a ballerina and dance on the stage of the Bolshoi Theater. In Paris I studied at the Kshesinskaya studio, which was the best in Europe. <...> My father treated Kshesinskaya with great respect. He understand better than anyone that the path of a great artist is not always strewn with rose petals,” said Marina said in an interview with Kommersant.

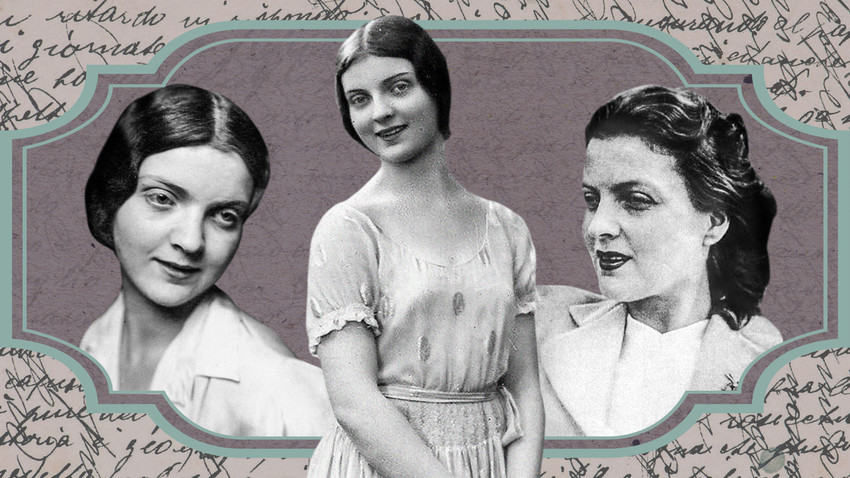

Sorin Savely Abramovich. Portrait of Marina Feodorovna Chaliapina

Private collectionIn 1927 Chaliapin, a great artist indeed, was forbidden to return to his homeland. The reason was the charitable help he provided to émigré children, for which he was stripped of his People’s Artist title and again had all his assets seized. The Soviet government could not tolerate the fact that Chaliapin lived with his mistress Petsold, whilst being officially married in Russia. The family finally realized that their place was now in Europe.

Marina Chaliapina had no particular desire to become Miss Russia, but it appealed to her sense of adventure, plus she felt pressure from other eminent Russian émigrés. “I just danced one evening at Matilda Kshesinskaya’s place. In the hall was [Nobel Prize in Literature winner Ivan] Bunin, [impressionist Konstantin] Korovin and, I think, [writer Alexander] Kuprin. It was their idea to elect a Miss Russia among the émigré ladies. They looked at me studiously, then announced unanimously: ‘That’s our Miss Russia!’”

After some persuasion, Marina accepted. There were no fashion shows in swimsuits back then; the competition was, first and foremost, about good manners, talent and noble birth. Everything was expected to “proceed in an atmosphere of impeccable morality, with the moral qualities of the candidates playing the primary role.”

Fyodor Chaliapin with his daughter Marina in America.

SputnikAfter her victory, Marina acquired a legion of admirers — after all, she was recognized as the most beautiful women of the Russian émigré community. Her suitors even included the Siamese prince Chula Chakrabon, whom she considered her secret fiancé for 10 years.

Chaliapin's family. Tyrol. Kitzbuehel. 1934

Museum A.M. Gorky and F.I. Chaliapin, KazanMarina did not make it as a ballerina, due to a leg injury. Instead, she became interested in car racing. Then, in 1938, returning from Rome to Paris to visit her father, she learned from an airport customs officer that he had died of leukemia.

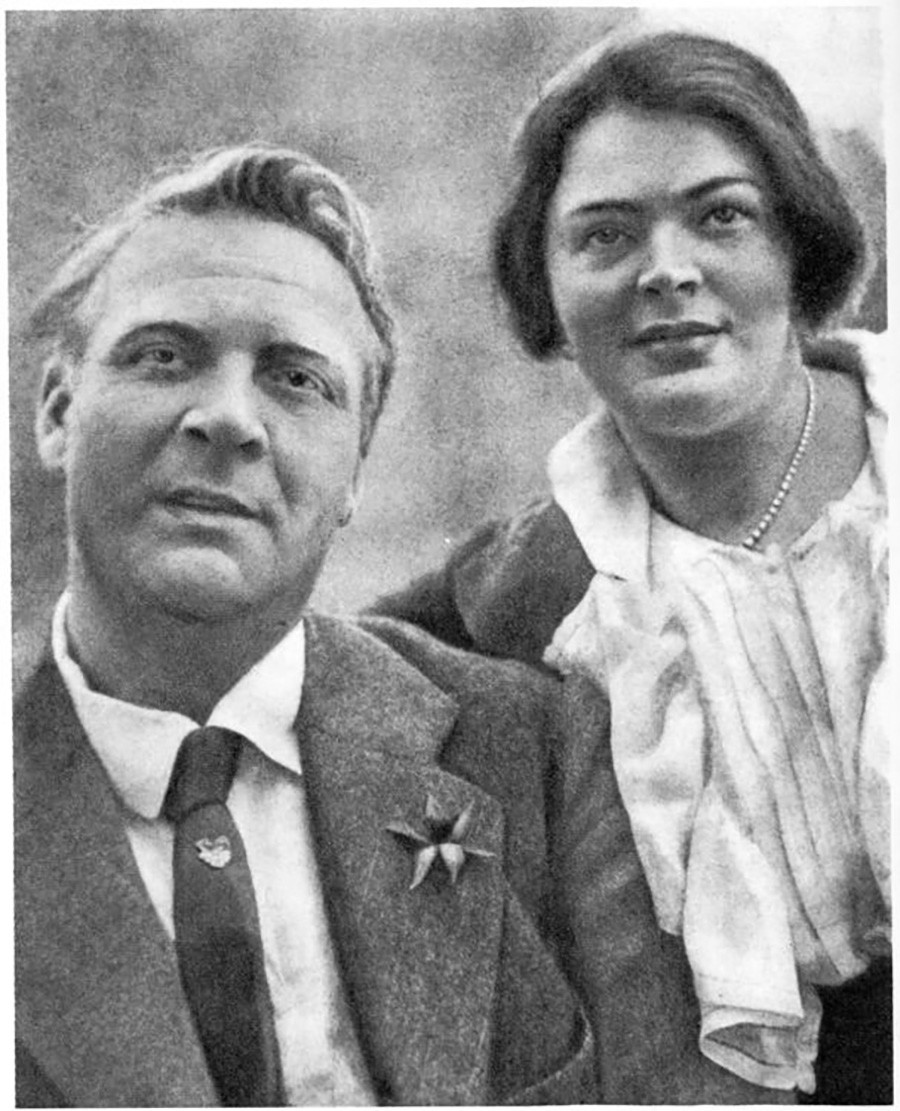

After the death of her father, she went to New York to study at the School of Interior Design, before moving to Vienna, this time to become a theater and ballet director. But not for long. In Vienna, friends invited her to Italy to work on a film about ballet. Marina agreed, and there she met her future husband, Luigi Freddi, who was 17 years her senior.

Luigi Freddi, already head of the General Directorate of Cinematography, was later appointed Italian Minister of Culture. He organized the first Venice Film Festival, and in 1937 founded and directed Cinecittà Studios, Europe’s largest filmworks. Marina, now using the double-barrelled surname Chaliapina-Freddi, starred in three of her husband’s movies: Old Times, Only for You, Lucia and Nobody’s Children.

However, she was forced to abandon her film career when Luigi, after the collapse of the fascist regime, was accused of collaboration with Mussolini, arrested and stripped of his property. He was soon released, but could no longer work, so Marina had to become the family breadwinner. Being fluent in five languages, brilliantly educated and well-versed in art history, she quickly found employment with Italian Line, the operator of a luxury transatlantic liner between Genoa and New York, where her job was to entertain first-class passengers. This position entailed being conferred the rank of Italian naval officer.

Marina Chaliapina at her father's grave

TASSMarina spent, in her own words, 40 very happy years with Luigi. His death came in 1977, and she survived him by 32 years, passing away in 2009 at the age of 98. She was buried in the Laurentino Cemetery in Rome, in the Freddi family crypt. Having outlived all her siblings, she did not give up alcohol, cigarettes, expensive cars and the bohemian lifestyle until the very end.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox