5 things that were once in place of Lenin's Mausoleum (PHOTOS)

1. Aloisio’s Moat

"Nikolskaya tower of the Moscow Kremlin and the Aloisio's moat in the 1800s" by Fedor Alekseev.

Public domainThe first ruler to thrust the shovel into the soil of the Red Square in Moscow was Grand Prince of Moscow Vasiliy III, father of Ivan the Terrible. And by Red Square, we mean the area right outside the walls of the Moscow Kremlin, built by Italian architects in the late 15th century.

Vasiliy III ordered a moat to be dug around the Kremlin, supplied with water from the Neglinnaya River that flows near the Kremlin. Italian architect Aloisio the New (Aleviz Fryazin, also known as ‘Aloisio from Italy’ in Russia) was in charge of moat engineering, which is why the moat came to be called ‘Aloisio’s Moat’. The moat was finished in 1519 and existed as a defensive structure at least until late 16th century, when parts of the moat were drained.

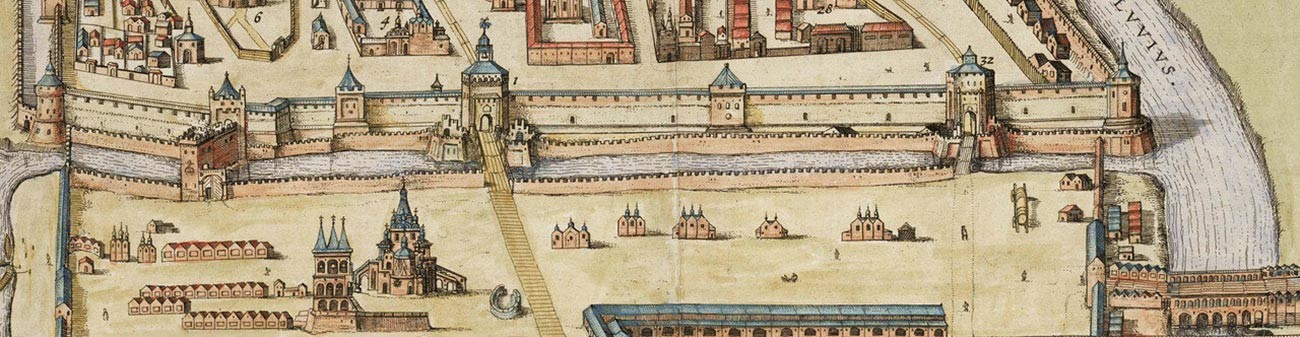

The Aloisio's moat on a 17th-century etching

Public domainIt is important to note that the official Russian Orthodox name of St. Basil’s Cathedral is still ‘Cathedral of the Intercession of the Most Holy Theotokos on the Moat’ – the only name where Aloisio’s moat is still mentioned. Because, initially, in 1561, when it was finished, it stood on the bank of the moat.

2. Ivan the Terrible’s zoo

The Red Square in Moscow, 19th century, by Fedor Alekseev. To the right, the moat can still be seen – that's where lions and elephants were probably kept in the 16th century.

Fedor AlekseevIn the mid-16th century, the part of the moat between Nikolskaya and Spasskaya towers – the very part where Lenin’s Mausoleum would appear in 1924 – was drained and used by Ivan the Terrible to hold a lion and a lioness presented to him by Mary I of England.

An elephant, a present from Persian Shah Tahmasp I, also lived in the moat for some time. The elephant was lavishly fed and his Persian minder received a good salary, which enraged the poor Moscow townsfolk. When, in 1570, the plague spread through Moscow, many blamed the beast. So, the elephant and his minder were sent away to the Tver region.

READ MORE: The elephants that entertained Russian tsars

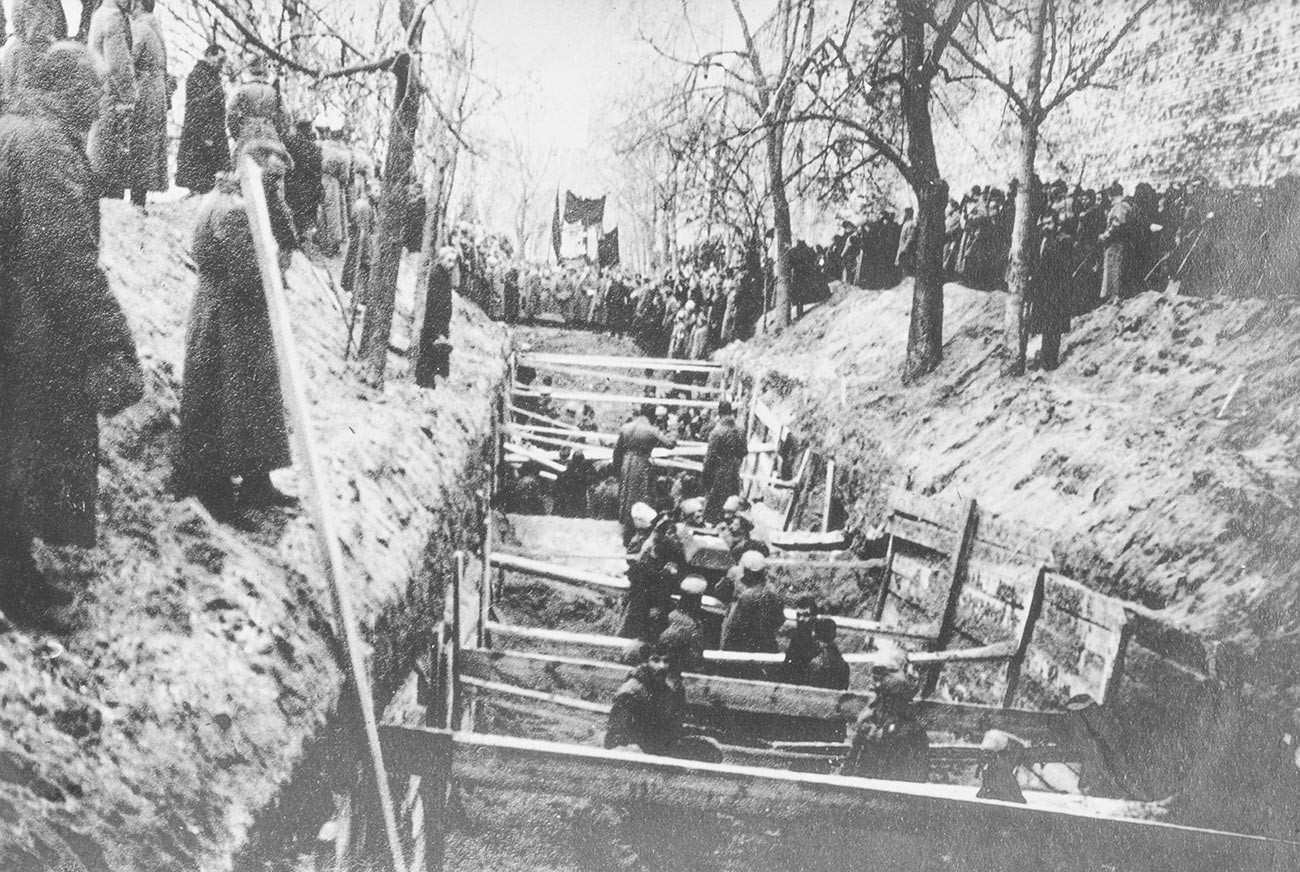

The wall of the Aloisio's moat, revealed during 20th-century excavations at Red Square.

Archive photoAnother elephant lived in the moat in the 17th century, a present from Abbas II of Persia to Alexey Mikhailovich, but it died of malnutrition.

Aloisio’s moat was once again used as a defense structure under Peter the Great, but was drained again in the 1770-1780s. By the beginning of the 19th century, the moat was filled with rubbish and debris. Alexander I ordered the part on the Red Square to be filled with soil.

3. Tram line

The first tram line, next to the Upper Trading Rows (GUM).

Public domainFor almost a hundred years, the place where the Mausoleum now stands was flat. In 1909, a tram line was installed on the Red Square – there already was a traffic problem in downtown Moscow, so the authorities tried to unload the transport network of the city with a ring layout by laying radial routes. But, immediately, a scandal broke out.

The line initially crossed the Red Square near the Upper Trading Rows (where the GUM Department store now stands). Enraged with the contemporary machinery’s intrusion into the ancient forum, members of the Imperial Russian Archaeological Society wrote a collective letter to the Moscow authorities: “Who allowed such a blatant distortion of this wonderful place in Moscow? The view of the monument to Minin and Pozharsky, St. Basil’s Cathedral, the Spassky Gate and the Kremlin are cut through by curved lines of wires and blocked by pillars!”

The tram line at Red Square, close to the wall.

Public domainThe Moscow intelligentsia, on the other hand, were firmly against removing the tram line and the city peddlers and shopkeepers also didn’t want the tram to be banned, because it guaranteed constant flow of customers through the Red Square.

Eventually, the line was moved closer to the Kremlin wall. If it existed now, it would run right next to the Mausoleum – and it actually did for some time, before the 1930s, when the Soviets needed to clean up the Red Square to hold vast military parades.

4. The Kremlin wall necropolis – and a rostrum

The first burials near the Kremlin wall.

The US Congress libraryIn October 1917, an armed uprising led by the Bolsheviks happened in Moscow – it lasted from October 25 to November 2 (O.S.). Thousands perished and the revolt ended with Bolshevik victory. One of the first orders of the newly founded Bolshevik Moscow authorities was to organize a solemn burial of the most distinguished revolutionary fighters who died during those days.

On November 8, 1917, two 72-meter graves were dug between the tram line and the Kremlin wall. On November 10, 1917, 238 coffins were buried there. Almost all factories and entertainment venues were closed in Moscow that day. At the opening of the necropolis, after Vladimir Lenin’s speech, a choir performed a cantata based on Sergei Yesenin’s poem ‘Sleep, beloved brothers, in light of the imperishable tombs’. The funeral was over at dusk and the graves were filled up by the next morning. Over the next week, two more bodies were buried.

READ MORE: How Lenin's body was attacked

Later, 15 more mass graves were dug near the wall – in total, there were over 300 burials. In 1928, already after the Mausoleum was built, the burials of ‘ordinary revolutionaries’ were stopped. Only the most distinguished Soviet and foreign Communists were buried there – Sergey Kirov, Maxim Gorky, Georgy Zhukov, Leonid Brezhnev and others. In total, the necropolis holds over 400 coffins.

The rostrum near the Kremlin wall during the May 1st (Labor Day) celebration.

Archive photoA rostrum was put up in 1917 in the center of the necropolis, right behind the place of the Mausoleum – the Bolsheviks used it for their public appearances. Also, following Lenin’s order, in the first years after the Revolution, the Spasskaya Tower clock would play a funeral march twice a day, at 9 AM and at 3 PM, to honor the victims of the Revolution.

5. The monument to a worker

The monument to a worker before its demolition.

Archive photoBy 1922, the rostrum was rebuilt – made smaller and in red brick to match the Kremlin wall. A temporary monument called ‘Worker’ was erected next to it – the creator, sculptor Friedrich Leht (1887-1961), made it out of gypsum.

The monument to a worker during a celebration of the 5th Anniversary of the October Revolution, 1922

Archive photoThe monument depicted a worker standing next to an anvil, his hammer leaning against his legs. His raised hand was holding his working headwear, saluting the Revolution. The worker’s figure was 4.3 meters tall.

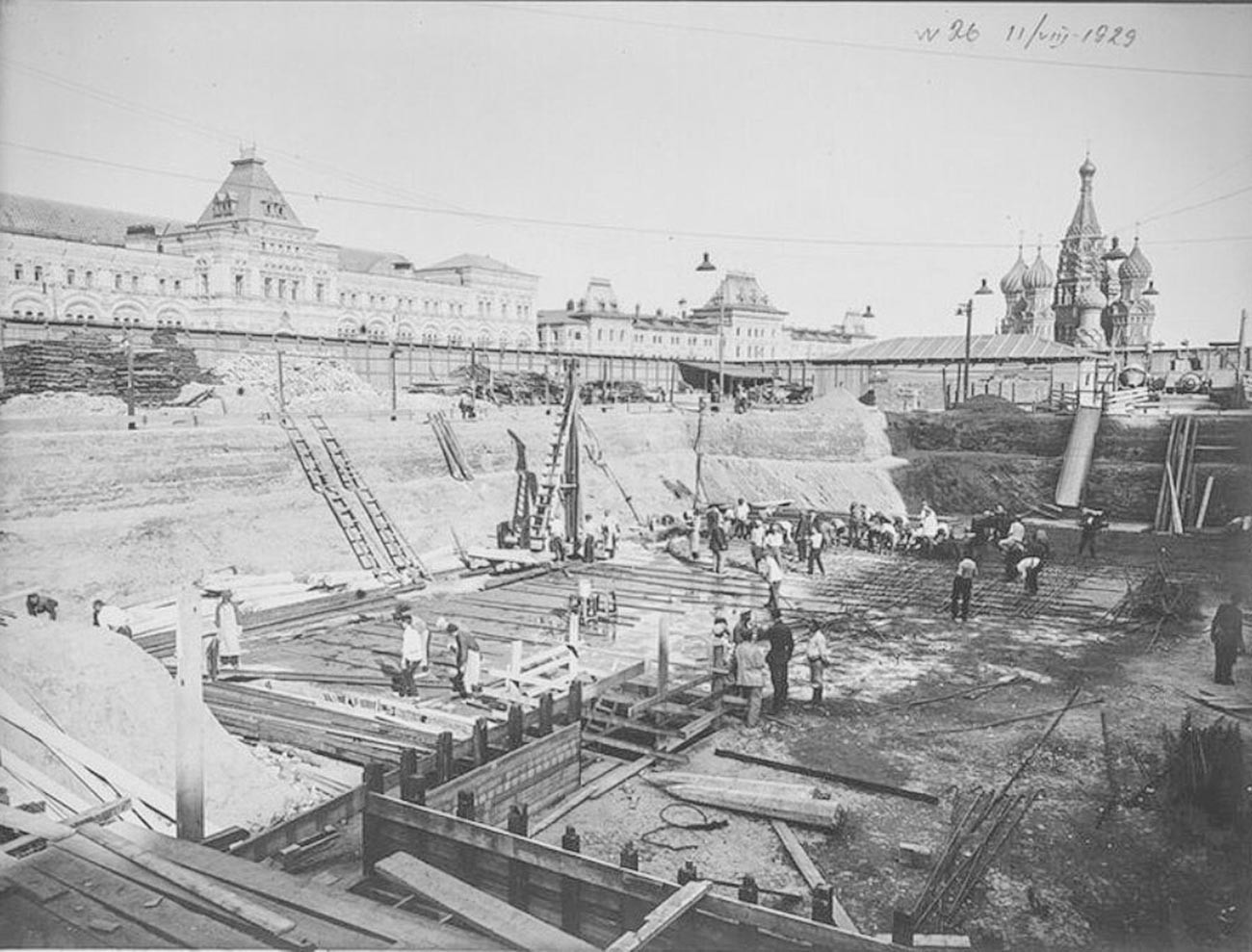

Building the new Mausoleum.

ROSPHOTO State Museum and Exhibition CenterThe monument continued to stand in its place when Lenin died and it was still standing when the first wooden Mausoleum appeared and the rostrum was taken down. But, in May 1924, when the construction of the second wooden Mausoleum started, the ‘Worker’ was removed and probably destroyed because of its material – no traces of this sculpture could ever be found.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox