Who are the foreigners buried with honors on Moscow's Red Square?

Red Square is the very heart of Russia, and it’s home to two of the country’s most important historical sites that probably everyone across the globe has at least seen a photo of: St. Basil’s Cathedral and Lenin’s Mausoleum.

Built in 1924, shortly after Lenin’s death, the Mausoleum is just part (albeit the central one) of a large necropolis near the Kremlin Wall. This cemetery for communist dignitaries was founded after the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution.

The temporary wooden mausoleum in 1924

Public domainImportant figures in the Communist Party and prominent revolutionaries were buried here up until 1985. On both sides of the Mausoleum are several graves marked with busts. In addition, there are mass graves with the remains of soldiers who died for the revolutionary cause.

An early burial of cremated ash in the Kremlin wall, 1920s

BundesarchivFrom the late 1920s, when a crematorium was built in Moscow, urns with the ashes of important Soviet figures were interred in the Kremlin Wall. These include writer Maxim Gorky, the Red Army’s Marshal Georgy Zhukov, cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin and pioneering space rocket engineer Sergei Korolev. Their ashes are interred in the columbarium in the Kremlin Wall.

Busts and memorial plaques

Legion MediaThe first foreigners were buried in the Kremlin Wall’s necropolis soon after the Revolution. For example, five foreign communists who died near Moscow in 1921 were buried in a mass grave near the Kremlin Wall. They are Oskar Helbrich and Otto Strupat from Germany, Ivan Konstantinov from Bulgaria, John Freeman from Australia and John William Hewlett from Great Britain; each had come to Russia to attend a congress of the Red International of Labor Unions. All were activists fighting for the rights of miners.

On the way to Moscow from Tula, where they had a meeting with miners, they participated in the test-run of an experimental high-speed railcar known as the Aerowagon, which crashed and killed seven of the 22 people on board.

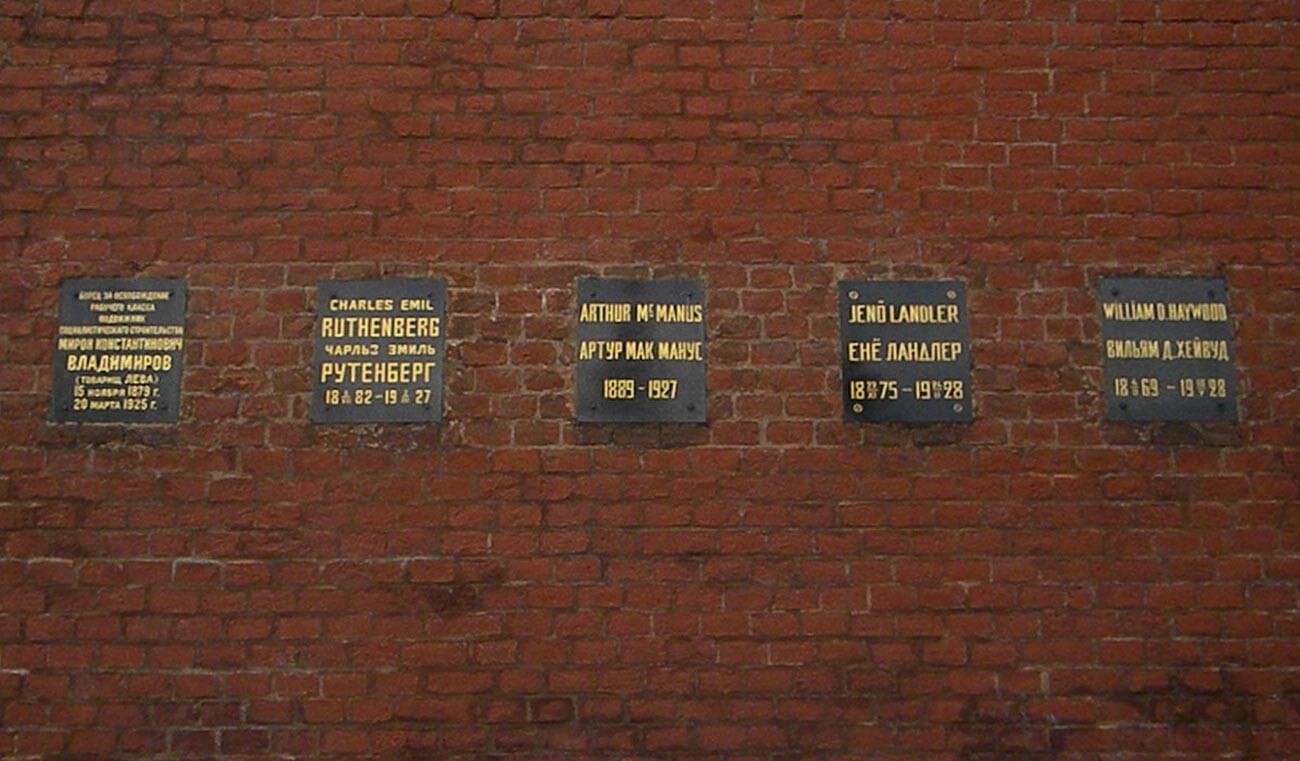

Memorial plaques of foreigners buried in the Kremlin Wall

Tothkaroj (CC BY-SA 4.0)There are many other foreigners among the nearly 200 people buried near the Kremlin Wall: most were leaders of labor movements in their home countries.

1. Antal Horák (?-1918), Hungary

After World War I, tens of thousands of Hungarian prisoners of war, including peasants, workers and other members of the lower classes, ended up in Russia. They decided to join the Bolsheviks and help in the struggle for power. (Click here to find out more about Hungarians' contribution to the Bolshevik Revolution.) Antal Horák joined the Red Army and was killed in the Civil War during the Bolshevik suppression of the Left Socialist-Revolutionaries' uprising. He was buried in a mass grave near the Kremlin Wall.

2. Augusta Aasen (1878-1920), Norway

Augusta Aasen

Public domainThis Norwegian communist was one of the organizers of a movement of solidarity with Soviet Russia. In 1920, she was invited to Moscow to take part in the Second Congress of the Comintern and in the First International Conference of Communist Women. She was killed in an accident during an air show in Moscow when she was hit by the wing of a plane when it crashed. Aasen was buried in a mass grave with several other communists who died in 1920.

3. John Reed (1887-1920), USA

John Reed

Public domainThis American journalist was perhaps the Bolsheviks' most favorite foreigner. Reed was personally acquainted with Vladimir Lenin and Leon Trotsky, witnessed the 1917 Revolution and chronicled it in his book Ten Days That Shook the World. After that, he even became one of the founders of the Communist Party of the United States. In 1919, he returned to Soviet Russia again, worked for the Comintern and traveled around the country to collect material for a new book. Reed died of typhus in Moscow in 1920 and was buried in a mass grave by the Kremlin Wall.

4. Charles Emil Ruthenberg (1882-1927), USA

Charles Emil Ruthenberg

Public domainA former carpenter and a son of a loader, Ruthenberg became the general secretary of the newly established Communist Party USA. He admired the socialist revolution that had taken place across the ocean and even staged a workers' demonstration under the slogan "Hands off Soviet Russia!" Ruthenberg died in his homeland, but at the request of the Bolsheviks, his ashes were brought to Russia and buried by the Kremlin Wall.

5. Arthur MacManus (1889-1927), Great Britain

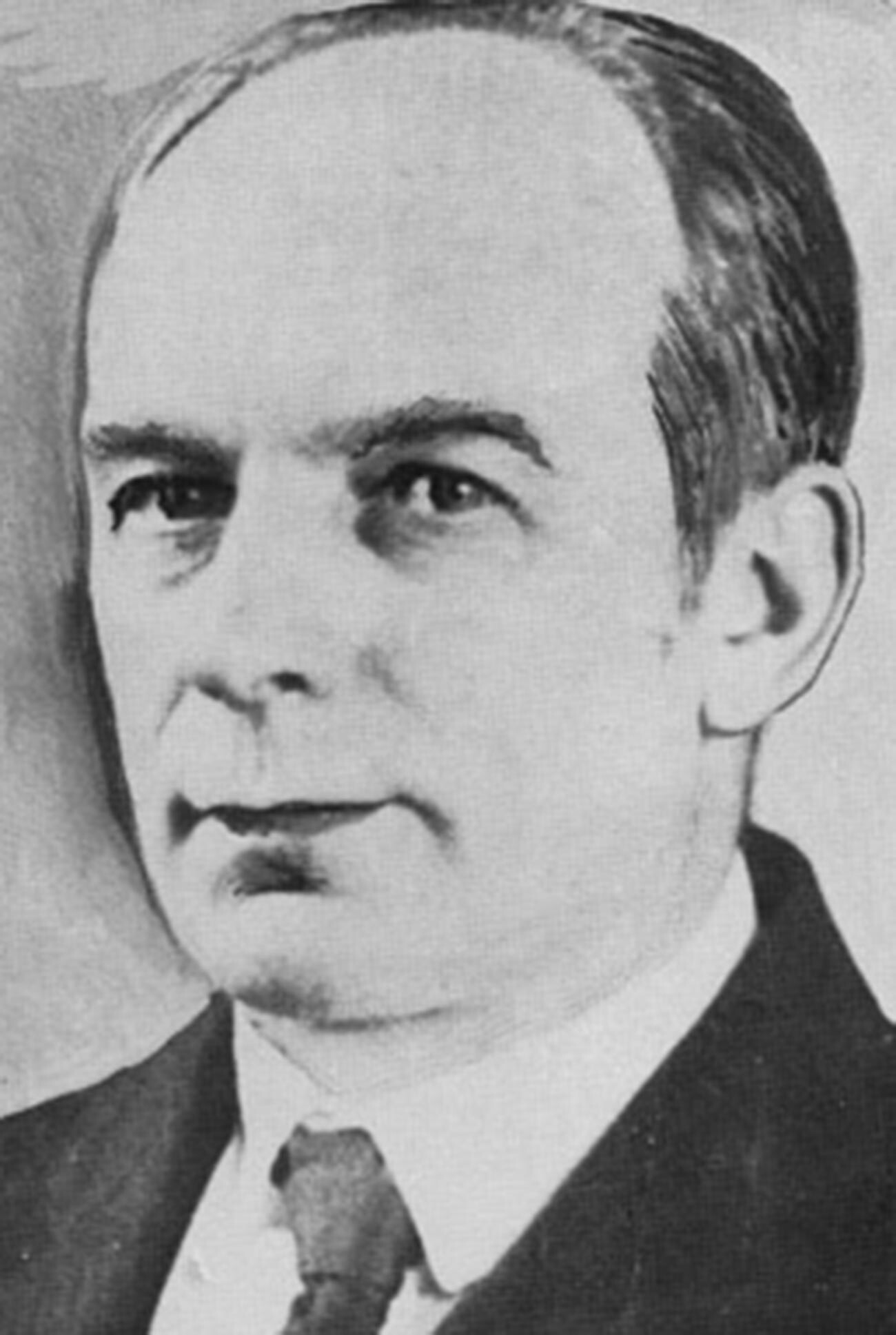

Arthur MacManus

Public domainThis Scottish metalworker took part in workers' strikes in the early 1910s and was a member of the Socialist Labor Party. He was also one of the leaders of a newly established organization - the council of shop stewards. He was very much inspired by the 1917 Revolution and began to campaign for the creation of a communist party in Great Britain that would unite all the left political forces. When that party was created, McManus visited the USSR in 1922 to attend the congresses of the Comintern. In 1925, he ran afoul of British authorities and spent several months in prison for inciting mutiny. He was released, but in early 1927 he died of influenza . His ashes were sent to the USSR and buried by the Kremlin Wall.

6. William Dudley Haywood (1869-1928), USA

William Dudley Haywood

Public domainHaywood, who worked as a miner, belonged to a regional federation of miners and was an active member of local leftist parties and workers' organizations, taking part in organizing strikes. Just like many other communists, he was against the U.S. entering the First World War. Haywood and his fellow activists were arrested on charges of espionage and incitement to desertion from the army. He was sentenced to 20 years in prison, but was soon released on bail.

He then fled to Soviet Russia: while in prison, he had developed great admiration for the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917. In the USSR, he did a lot of work for revolutionary workers' organizations, wrote an autobiography and a book on the history of the labor movement in the U.S. Both were published in Russian. He died in Moscow in 1928.

7. Jenő Landler (1875-1928), Hungary

Jenő Landler

Public domainAs a young man, this prominent Hungarian communist organized several workers' strikes. Later, he became one of the leaders of the short-lived Hungarian Soviet Republic and was in charge of the Hungarian Red Army. After the republic was defeated, he emigrated and cooperated with the Comintern. He died in 1928 in Cannes from an illness. His ashes were interred in the Kremlin Wall. Another Hungarian national and a fellow member of the Hungarian Communist Party, Jenő Hamburger, was also buried in the Kremlin Wall, in 1936. However, after World War II, his ashes were returned to Hungary.

8. Clara Zetkin (1857-1933), Germany

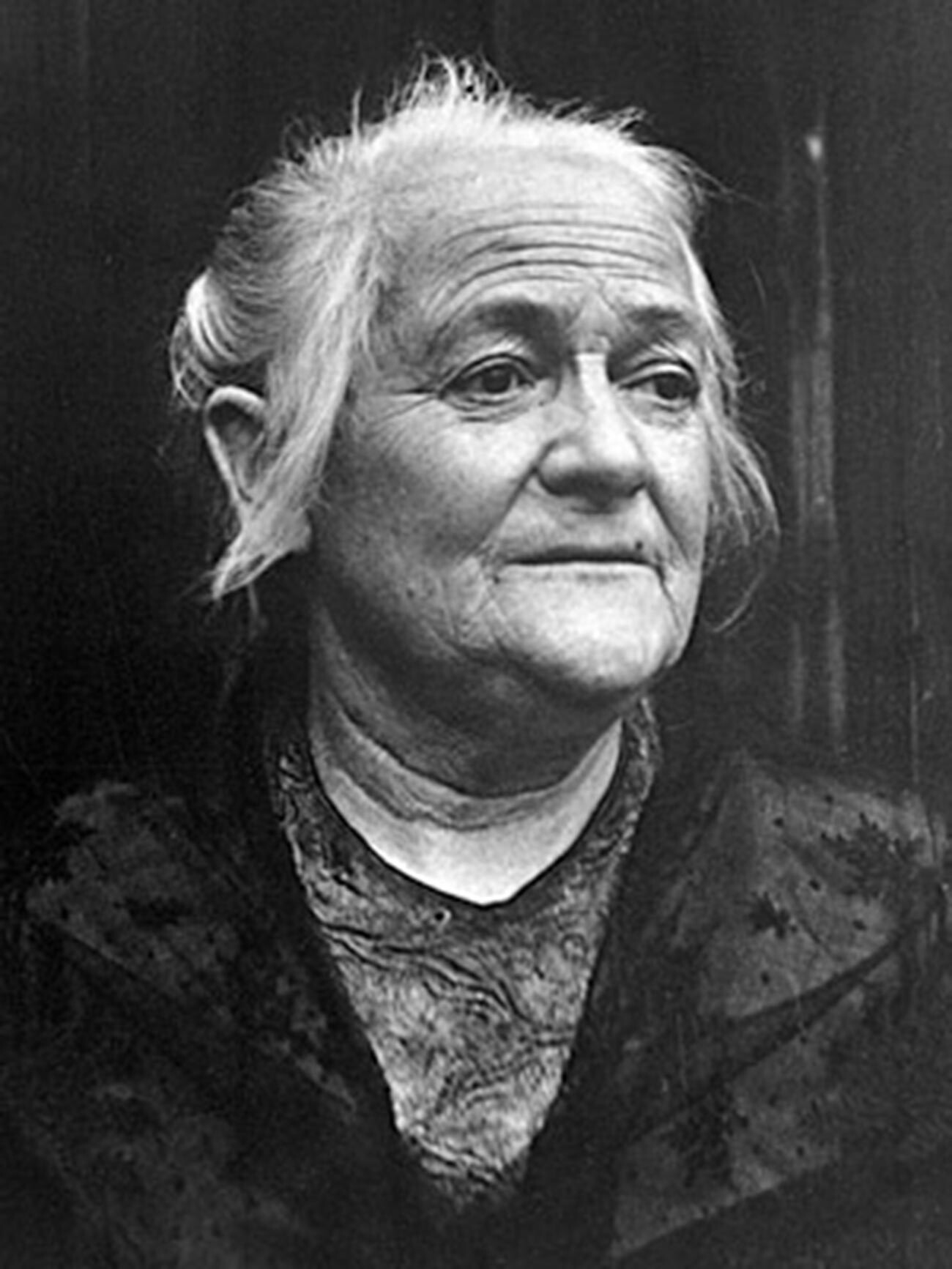

Clara Zetkin

Public domainThe name of this German communist and champion of women's rights was known to every Soviet citizen from childhood: many streets in Russian cities are still named after her, and one of Russia's favorite national holidays is International Women's Day on March 8, which she helped establish. Zetkin was expelled from Germany when Hitler came to power. She died near Moscow in 1933.

9. Sen Katayama (1859-1933), Japan

Sen Katayama

Public domainThis Japanese activist became a communist while studying in the United States. When he returned to his homeland, he began to set up trade unions and labor movements, as well as a left-wing party. When Russia was at war with Japan in 1904, he shook hands with the socialist Georgy Plekhanov - both were elected chairman of the Congress of the Workers' International. During reprisals for organizing workers' riots, he left Japan and in 1918 he moved to Soviet Russia, where he worked in the Comintern. He died in Moscow in 1933.

10. Fritz Heckert (1884-1936), Germany

Fritz Heckert

Loracco (CC BY-SA 4.0)A prominent figure in the labor movement, Heckert was a member of the German Communist Party’s leadership. He knew Lenin well and admired the success of the revolution in Russia. Heckert, like Zetkin, was forced to leave Germany after the Nazis came to power. He then lived in Moscow and wrote for Soviet newspapers.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox