A man with a beard looks into the future with dignity.

Kira Lisitskaya (Photo: Legion Media)A loud scandal shook Moscow society in the late 1520s: Grand Prince Vasily Ioannovich shaved off his beard and left only a mustache, “Lithuanian style”. Rumor had it that he did it to flatter princess Elena of the Glinsky family, who was 29 years younger than the Grand Prince. Having become the wife of Vasiliy, Glinsky soon gave birth to an heir – the future Ivan the Terrible. But, long after that, the boyars and the nobility trembled with anger – because shaving a beard in those times was forbidden by the Orthodox church.

"The Great Gosudar, Tsar and Autocrat of All Rus'," by Sergey Ivanov, 1907. Tsar Alexey Mikhailovuch Romanov is pictured. Note the beards of his closest boyars.

Sergey IvanovBeard – everybody

Mustache, no beard – A Lithuanian or a Pole

No beard, no mustache – a “nemchin” (a European, a Catholic, an alien person)

In ancient and medieval Russia, a beard and mustache were common for all men. Even ‘Russkaya Pravda’ (‘The Russian Truth,’ the first code of laws in Russia) recognized the special status of a beard – if someone deliberately damaged someone else’s beard (cut, burned or tore through it), he paid a fine.

Over time, beards began to be cut – as in Europe in early modern times, a beardless face became a sign of a high social status. In Russia, the new fashions were resisted. In 1551, the Orthodox church forbade shaving and cutting mustaches and beards – under pain of excommunication. With the constant confrontation between Orthodoxy and Catholicism and the constant attempts of the Catholic Church to preach among the Orthodox population, shaving or wearing beards was also a political issue.

"A Polish nobleman," by Alexander Orlovsky

Alexander OrlovskyA beard in pre-Petrine Russia was not only a source of pride – people even swore by it. Traveler Adam Olearius noted that of all the Moscow boyars, the greatest respect is paid to those with a large belly and a long beard. “His majesty exhibits such men at solemn audiences, thinking by this to instill a greater respect for his person in foreigners,” Olearius wrote.

"Polesovschik" ('Ranger'), by Ivan Kramskoy, 1874

Ivan KramskoyBeard – peasant, rich merchant, a priest or member of the clergy, an Old Believer

No beard, no mustache – everybody else

A man with a “bare face” on a Russian street attracted attention in one way or another. The first thought was: “It’s a foreigner, a German or a Lithuanian!” But, by the end of the 17th century, there were so many foreigners that the fashion for hairstyles and cutting beards penetrated into Russia’s youth, as well.

In 1675, Moscow nobility had to be reminded by a special decree “not to adopt foreign German and other customs and not to cut hair on their heads and also not to wear dresses, caftans and hats and not to let their own people wear them either”.

And, in 1698, Peter, just back from the Great Embassy, gathered his boyars and, telling them about the campaign, began to cut their beards. The shocking action was repeated at the next feast in the presence of the tsar and at another one…

"Portrait of Akinfiy Demidov," by Georg Christoph Grooth, 1740s. Akinfiy Demidov was a famous Russian industrialist, founder of mettalurgical 'empire' of the Demidov family.

Georg Christoph GroothBecause, in Russia, a man without a beard looked like a foreigner, while the bearded members of Russian embassies in Europe looked like barbarians. Peter understood that for the success of trade and cultural exchange with Europe, this psychological barrier had to be removed. From 1700 onwards, everyone was commanded to wear “German” dress, except clergy, cabmen, and peasants, and, from 1705, the famous “beard fee” was introduced in the cities. It did not apply to the countryside – peasants continued to walk bearded, but to enter the city, they had to pay a kopeck.

If townspeople wanted to wear a beard, the tax was huge – wealthy townspeople were charged 60 rubles a year, poorer townspeople – 30 rubles, rich merchants – 100 rubles a year, Old Believers – 50 rubles a year. At the same time, a soldier in the army received 10 rubles a year. Can you imagine how expensive it was to have a beard?

There were beard checks at all the city gates and patrols went up and down the streets. Grigory Esipov, a historian, described those times: “A poor merchant or peasant brings stuff, logs, wood, coal or any other goods to town. At the city gate, he is shouted at: ‘Stop! What about the beard?’ A kopeck goes into the pockets of guards – and, if the man does not want to pay, they send him to the provincial chancellery and, from there, to prison – and he sits in it for a long, long time: where can a poor man get 50 rubles? In the provincial chancellery in St. Petersburg in 1723, there were so many bearded people in jail, poor traders and industrialists, that the Senate ordered them to shave their beards and let them out on bail.”

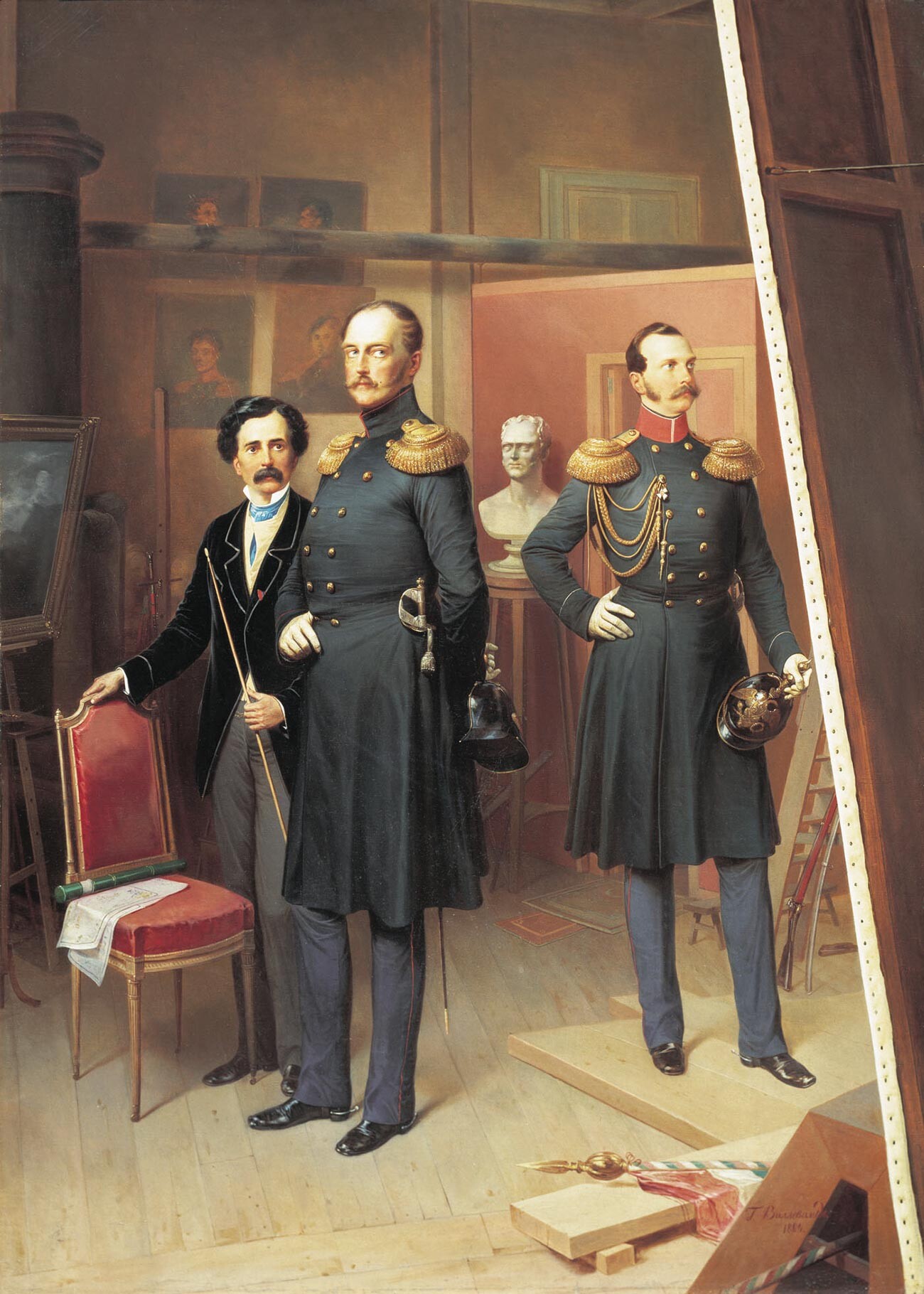

"Nicholas I with Heir Apparent Alexander Nikolaevich in the artist's studio in 1854," by Bogdan Villevalde

Bogdan VillevaldeBeard – peasant, rich merchant, a priest or member of the clergy, an Old Believer

Beard (while wearing a stylish attire) – a dandy, a freethinker;

Mustache, no beard – a military man;

No beard, no mustache – everybody else.

From 1762, Catherine the Great abolished the beard fee for civilians – while the military men continued to shave according to army regulations. Nevertheless, it was no longer customary in Russian society to wear a beard. Old Believers, on the other hand, were given the right to walk with a beard without any fines.

With the advent of the 19th century and the era of ‘dandyism’, the beard became a sign of reclusiveness. Emperor Alexander I himself said that he would grow a beard and retire to Siberia if the war with Napoleon was lost.

From the 1830s onward, the beard became the mark of the dandy. As the ‘Ladies’ Journal’ wrote: “Many young men imagine that they will attract attention if they let their beards down, just as the citizens of the ancient Greek and Roman republics did.” However, such fashionable men were not popular in society - they were compared to “soiled Cossacks”, dervishes and even goats.

Old Believers of Nizhny Novgorod

Public domainWhat was the surprise of society when, in 1832, military ranks were allowed to wear a mustache and sideburns. Why did this happen? Very simply – for some reason, Emperor Nicholas I himself started wearing a mustache, so he had to allow the same to the entire army (Nicholas was in the military rank of general engineer). However, the emperor soon noticed that civil servants, especially in the provinces, began to wear a beard and mustache. In 1837, Nicholas had to issue a decree, which said: “The heads of civil authorities must strictly watch that their subordinates wear neither beards nor mustaches, because those belong to the military only.”

Under Nicholas, the only “official” civilian with a mustache was court painter Bogdan Villevalde: the emperor posed for him so often that the painter petitioned for the right to keep his luxurious mustache, which he dubbed “the Most Highly Approved mustache”.

"Portrait of a private of the Company of the Palace Grenadiers, M. Kulakov," by Vladimir Poyarkov, 1915

Vladimir PoyarkovIn 1874, Emperor Alexander II allowed all military personnel (with the exception of the Guard, the Royal Entourage and the highest military and naval ranks) to wear mustaches and beards, while his son, the bearded Emperor Alexander III, immediately after his accession in 1881, allowed everyone without distinction of ranks to have a beard. Privates among the royal guards and royal grenadiers were even especially instructed “not to shave the beard”! From this moment onwards, hair on the face in Russia became not a subject of legislation, but a part of fashion.

Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox