Ever since 1957, when the USSR carried out the sensational first ever satellite launch in history, the country’s higher ups would constantly demand ever more impressive feats. Every four months, General Secretary Nikita Khrushchev would ask scientists: “So, what else have we got going on?” Good news was in short supply.

Before August 1960, the Soviet Union had already managed to send eight dogs to space, none of which made it back alive. It was always a one-way trip. The heart-wrenching story of the first mongrel they sent up there - Layka - aroused heated ethical discussions.

However, the space race carried too much political weight. The Soviets were obsessed with the idea of proving that animals weren’t the only ones that could make it back from space in one piece. Lisichka and Chayka - two other dogs - were sent into orbit in 1960. The flight ended in a catastrophe and the dogs’ deaths: at around the 23rd second of the flight, the combustion chamber fell apart. It was decided then that all future dogs were to be supplied with an ejecting capsule, so they could catapult to safety if something went wrong. This was actually the only change made to the Belka and Strelka launch, just 20 days before their space flight.

Belka and Strelka

SputnikAs the U.S. was launching monkeys into space, the USSR gave preference to dogs. “Firstly, the mongrels really fit the bill,” Professor MD Adilia Kotovskaya, who was in charge of preparing the dogs for the mission, said. “After all, they don’t live pleasant lives - there’s the cold, the hunger. Which means they’re adapted to different conditions. Secondly, dogs have a very good relationship with humans, whom they see as their masters. And they’re great at training. And thirdly, the dog’s physiology has been thoroughly studied since the days of Ivan Pavlov.”

Read more:Why did the Soviets send dogs into space, and not monkeys?

As with many other space dogs, Belka and Strelka were found roaming the street. A special department was tasked with turning the city upside down to find the perfect female specimens (it would be less challenging to produce sewage devices for females) aged 2-6, weighing under 6 kilos and no more than 35 centimeters in height. Lighter shades were preferred, as they came out better in press photos. Up to a dozen of these dogs could be seen at the Institute for Medical and Biological Studies, where the program was being developed.

Belka was made team leader, being the most active and communicative of all. She showed the best results all around, being among the first to approach her food bowl and the first to learn how to bark in an emergency. Strelka - the lighter dog with brown spots - was the more timid of the two, but, likewise, did excellent in all the tests. Both dogs were about two-three years of age.

The dogs were subjected to thorough medical tests and gradually taught to withstand what was to come: At first, their physical space would be limited for several days; the doctors would also hook them up to machines and test their ability to wear spacesuits, also teaching them how to handle G-force spikes.

When the time came to fly, the dogs were given their famous nicknames and made history. Prior to that, while they lived at the institute’s vivarium, they were called Kaplya and Wilna.

The flight was scheduled for August 19, 1960. The ejectable container also had 12 mice and a bunch of different insects, plants, seeds and fungal and microbial cultures. Outside of the immediate container with the dogs and other lifeforms were another 28 mice and two rats - all of the animals and microbes being there to test their resilience to space travel.

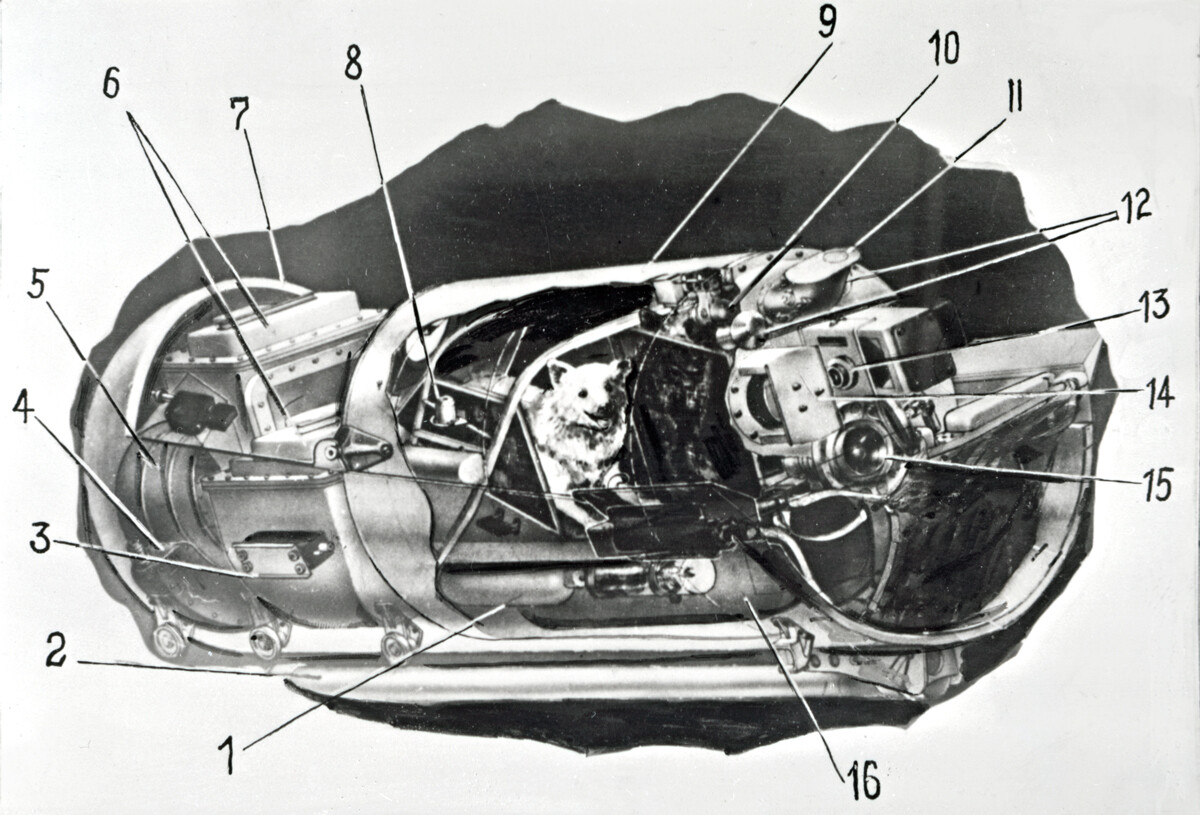

Animal cabin in an ejection container aboard a satellite ship

SputnikThe launch was also notable for the fact that it was the first time anyone saw a televised broadcast from space: the picture from the spaceship quickly made its way to the Earth-based space center, with only a short delay. During takeoff, the dogs were somewhat agitated, with higher heart rates and breathing. However, the moment the ship reached orbit, the indicators showed the pair was fine.

The food arrived soon after. The substance resembled the Russian meat and gelatin dish kholodets, which also provided the dogs with the necessary fluids. The tubs with space dog food attached underneath the seats, where they lay. A signal opened the containers, and once the dogs were finished, the trays went back. Belka and Strelka wolfed it all down with delight.

Later, during the fourth circumnavigation of the globe, Belka had become strongly agitated. She tried to wriggle out of her supports and began to throw up. Her vitals were all normal, however.

After the 17th loop was complete, the dogs were returned to Earth successfully, having spent around 27 hours in orbit. Junior science fellow V.S. Georgiyevsky, who was part of the rescue team, recalled: “As the apparatus was opened up, Belka and Strelka immediately recognized me and wanted cuddles. Their condition was good, even better than after some days in training. Their little noses were wet, the tongues - with which they were licking my hand - were pink. I calmed down and even let them go for a run around the steppe.”

Having analyzed the flight data, scientists concluded that no danger would befall a human if they were to be sent to space. Belka and Strelka’s launch was the last one of the animal kind.

The fact that Belka had felt discomfort in space was interpreted by scientists as stress, nothing life-threatening. Nevertheless, the situation resulted in the decision to limit the number of loops a human would have to perform down to a minimum. That was why Yury Gagarin would only make one round-the-world trip later on.

Belka and Strelka were honorably discharged and allowed to enter retirement, living at the Institute to a respectable old age. They were the most popular animals in the Soviet Union in the 1960s - their likeness adorning banners, posters, marquees, postcards and calendars.

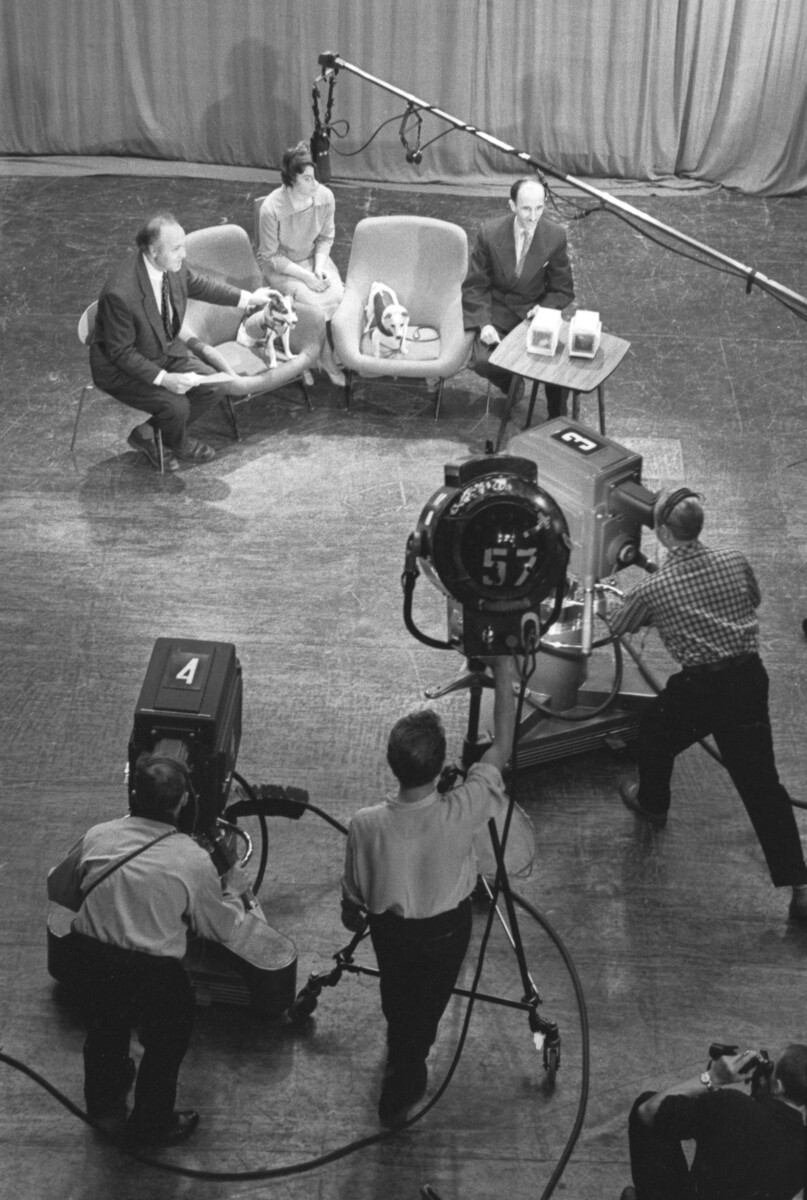

Several months after the flight, Strelka gave birth to six healthy pups, who were shown on TV. “There was one absolutely white puppy they called Pushok. U.S. First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy had really taken to him and, so, they decided to present her “the son of cosmonautics”. A large U.S. embassy delegation arrived in total secrecy, gathering documents on Pushok, getting his shots in order, then, later, practically with police in tow, took him to the American embassy. It was something to behold! Like they were transporting a prince or something!” Adiliya Kotovskaya recalled.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox