'Hussar Ballad'.

Director Eldar Ryazanov, 1962 / MosfilmThe recipe for the drink was brought to Russia by officers of the Russian army who had taken part in campaigns during the Napoleonic Wars. Similar to ordinary punch in its ingredients and method of preparation, it underwent modifications under the influence of the hussars, acquiring a new name, but retaining its strength and merriment-inducing effect.

Strictly speaking, zhzhyonka can be described as a punch of sorts. This is how in 1803 French historian Grimod de La Reynière described the effect of punch in his book ‘L'Almanach des gourmands’: "Punch produces merriment, stirs the imagination and almost never intoxicates". This last statement could be disputed - for the opposite was the case in Russia.

'Hussar Ballad'.

Director Eldar Ryazanov, 1962 / MosfilmOnce in the hands of Russian officers, the recipe was adapted and the words "almost never intoxicates" were no longer applicable. In the hussars' version, the making of the drink became quite a spectacle: a huge bowl was filled with wine, on top of which two crossed swords were placed. A block of sugar was positioned on top of them and rum was poured over the sugar. Then the sugar was set on fire and the burning sugar flowed into the wine, after which it was extinguished with champagne. This "fire" is what gave the drink its name ["zhzhyonka" is derived from "zhzhyonny", the Russian past passive participle of the verb "zhech’", meaning "to burn"].

'Hussar Ballad'.

Director Eldar Ryazanov, 1962 / MosfilmThe recipe could vary, however: sometimes brandy was used instead of rum, the wine could be red or white, and fruit could be added. In field conditions zhzhyonka was made from whatever was available, the objective being either to get warm in winter or build up courage before a battle. But in peacetime making it was turned into a whole ritual.

This is how a former hussar, Count Osten-Sacken, recalled the officers' tradition: "A zhzhyonka drinking party always had a military air about it: the floor in the room would be covered with rugs; in the middle of the room sugar would be burning in rum in some vessel, imitating a campfire at a bivouac; the revelers would sit around it in several rows with their pistols in their hands, the touch holes sealed with sealing wax. When the sugar melted, champagne was poured into the vessel and the pistols were filled with the ready-to-drink zhzhyonka - and the party began."

'Hussar Ballad'.

Director Eldar Ryazanov, 1962 / MosfilmZhzhyonka was called the "hussar's drink" because the scions of well-off and eminent families served in the hussar regiments - the so-called "gilded youth" of the 19th century. The hussars were among the few people who could afford such a luxury. An officer's pay was about 395 rubles a year, and for this money he had to pay his rent, keep a horse, purchase expensive uniforms and additionally shell out for food. The price of a bottle of champagne started at two rubles and French wine cost 50 kopeks upwards, while a pood (a traditional Russian unit of measure around 16 kg) of sugar cost in the region of 40 rubles. It was a very expensive drink to make, and, given the way of life of the hussars, with their reputation as hell-raisers and philanderers, one can imagine how much was squandered in a year on such revelry.

Officers of lifeguard Hussar regiment, 1838.

Public DomainThe fashion for the expensive, warming drink spread beyond the hussar regiments into literary and student circles. Alexander Pushkin, for one, was very fond of zhzhyonka. A friend of the poet, Ivan Liprandi, recalled the following incident in his memoirs. Gathering in convivial company, he and Pushkin, as well as colonels Orlov and Alekseyev, went off to the billiard room where they decided to drink some zhzhyonka. Three bowls were imbibed in all, which had a predictable effect on the poet: "Pushkin became merry and started going up to the sides of the billiard table and interfering with the game. Orlov called him a schoolboy, and Alekseyev chipped in that schoolboys are taught a good lesson… Pushkin wrenched himself away from me and, mixing up the billiard balls, gave as good as he got; it got to the point of his challenging both of them to a duel and inviting me to be his second." With Liprandi's mediation, the situation was defused: Orlov and Alekseyev apologized to Pushkin and the duel was called off.

Ivan Liprandi.

Public DomainMikhail Lermontov, who learned to make the drink in his student days at cadet school, also wrote fondly of zhzhyonka, while Nikolai Gogol personally cooked up batches for his guests. Zhzhyonka retained its popularity for the whole of the 19th century - in his ‘My Past and Thoughts’, published in 1870, Alexander Herzen recalled having one too many at a friend's name day party: "The next day, I had a headache and felt nauseous. Evidently from that zhzhyonka concoction! And I am sincerely determined never to drink zhzhyonka again - it's poison."

By the end of the 19th century, the popularity of zhzhyonka began to fade, before the fashion disappeared altogether. The makeup of officer regiments was becoming drastically different, too: few could afford such an expensive luxury. In the 20th century, zhzhyonka started only to be used in an initiation ceremony for the hussars, and after World War I the drink was essentially forgotten.

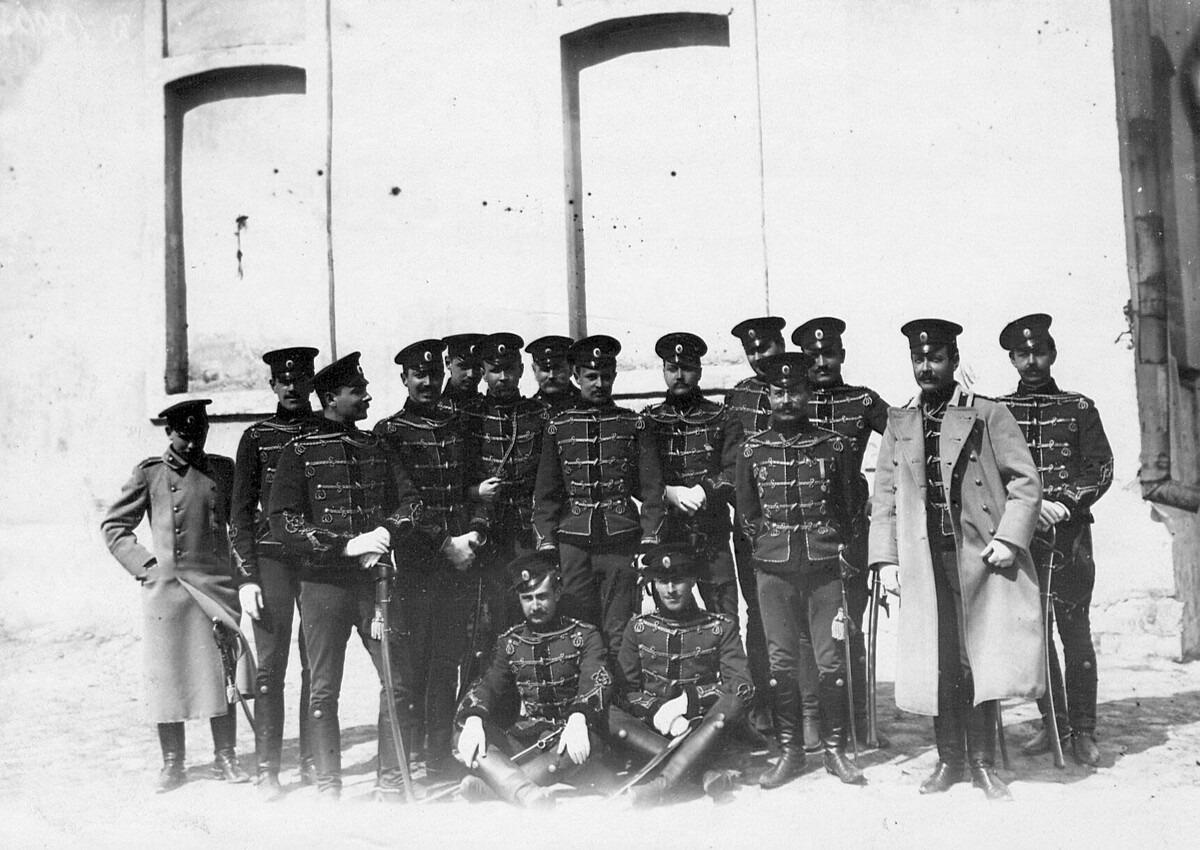

Group of hussars, 1900s.

Public DomainDear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox