The first Russian emperor who was assigned a number was Peter the Great. On October 22, 1721, the Russian Empire was founded. On this day, the Governing Senate and the Holy Synod of Russia formally presented Peter with the title of ‘Father of the Fatherland, Emperor of All Russia, Peter the Great’. But, the official manifesto about this was named ‘The Act on presenting […] Peter I with the title of the Emperor […]’

Peter was assigned the Roman-styled number ‘I’ to his title, because he wanted himself to be as valid as contemporary emperors – meaning, first of all, Charles VI (1685 – 1740), the Holy Roman Emperor from 1711. Peter was proud to actually be his relative – wife of Peter’s son Alexey was the sister of Elisabeth Christine of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel, Charles VI’s wife. So, when Peter passed away on January 28, 1725, the official manifesto named him Peter I and his wife – Catherine I.

Before the 18th century, Russian tsars and Grand Princes were just named using their name and patronymic: for example, tsar Alexey Mikhailovich (1629 – 1676) or, even earlier, Grand Prince of Moscow Vasiliy Ivanovich (1479 – 1533).

Portrait of Karamzin by Vasily Tropinin, 1818.

Tretyakov GalleryThe numeration continued in 1740, when Ivan Antonovich, the ill-fated heir to the Russian throne, was declared Ivan III by the Governing Senate. In the Senate’s logic, Ivan “the Terrible” Vasilyevich was the first Russian tsar, the second tsar named Ivan was Peter’s half-brother Ivan Alexeevich (1666 – 1696), so Ivan Antonovich was the third. Note the fact that the numeration was continuous although Ivan the Terrible was a Rurikid, while Ivan Alexeevich and Ivan Antonovich belonged to the Romanovs. By making the numbers continuous, the officials stressed the fact that the Romanovs and the Rurikids were related.

The numeration changed in the first quarter of the 19th century. In 1829, the complete ‘History of the Russian State’ by Nikolay Karamzin (1766-1826) was published. In his seminal work that became the main textbook on Russian history for almost a century, he started the numeration of Russian sovereigns from Ivan Danilovich, known as Ivan Kalita, Prince of Moscow.

Why? Ivan Kalita was the first Moscow ruler who acquired the right to collect tributes from the Russian people and transfer them to the Mongol-Tatars, gaining a certain extent of independence. He was also the grandfather of Dmitry Donskoy, who, in 1380, defeated the Golden Horde in the Battle of Kulikovo.

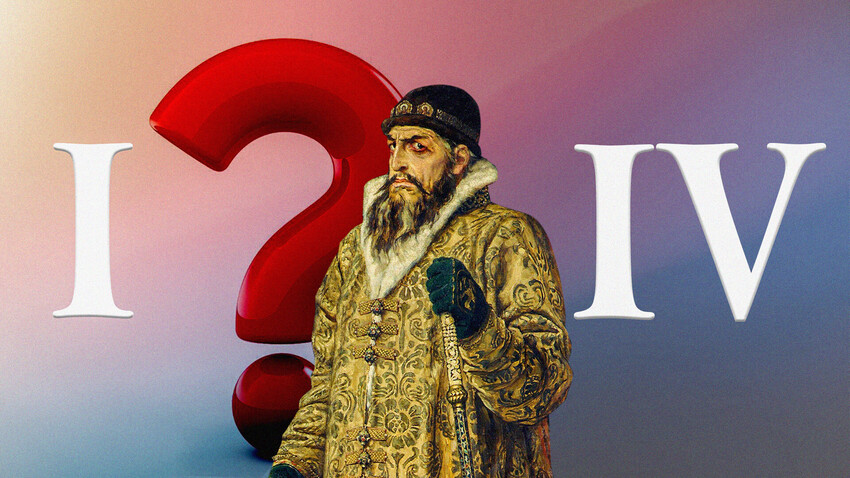

Nikolay Karamzin, didn’t approve of Ivan the Terrible’s politics and didn’t want to start the numeration of the Russian tsars with him – although, it would have been logical, as Ivan the Terrible was, indeed, the first tsar. But, after Karamzin’s ‘History…’ came out, it established the current tradition of numeration. According to it, Ivan the Terrible was the fourth in the line of Moscow rulers named Ivan: Ivan Kalita (1284-1340) was the first, his son Ivan Ivanovich “the Fair” (1326-1359) was the second, Ivan Ivanovich “the Great”, the founder of the Moscow state, was the third.

Thus, Ivan the Terrible became Ivan the IV, while Ivan Alexeevich, Peter’s half-brother, became Ivan the V, while Ivan Antonovich turned into Ivan VI.

Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox