How fake monks served Ivan the Terrible

"Oprich" in Russian means "apart from." And until the time of Ivan the Terrible, this word meant the remainder of the estate that was transferred to the widow of a deceased prince. All the property of the prince passed to his sons, except the "oprichnina," which was the portion that remained to the widow. The same word was used by Ivan the Terrible in choosing a name for his personal guard – oprichnina. They were warriors who were ‘apart’ from all the others.

Why did the tsar create the oprichnina order?

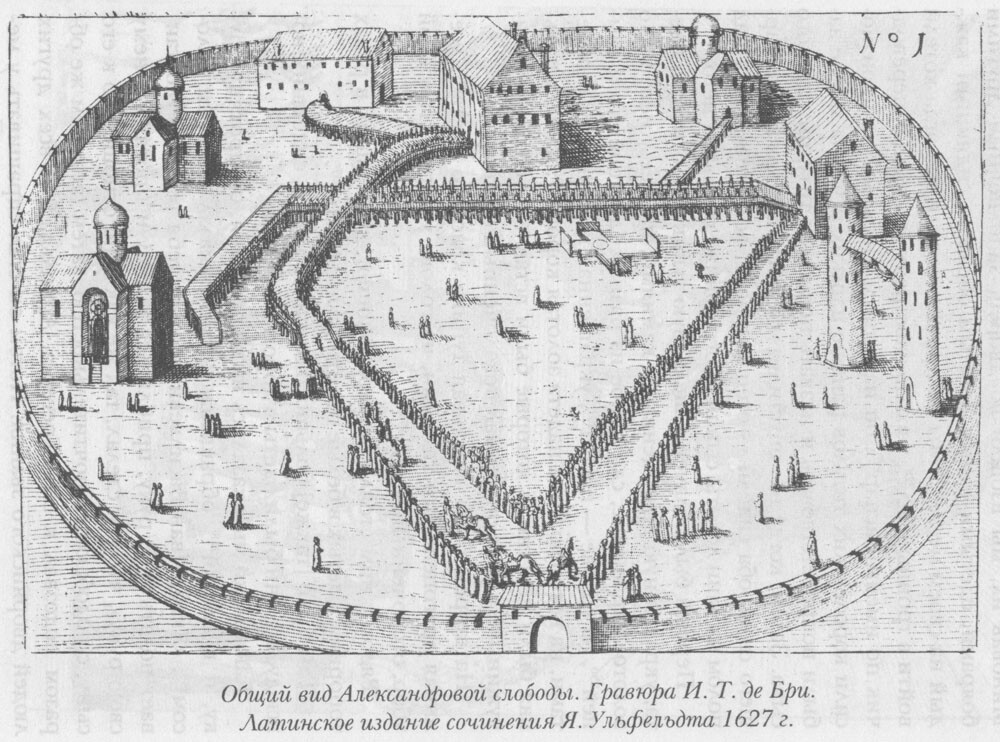

Alexandrov Sloboda, the oprichnina residence.

Alexandrov Sloboda, the oprichnina residence.

With the help of oprichnina Ivan the Terrible fought against the ‘oligarchs’ of his time. Large landowners, who were primarily noble princes of the ancient Rurikid dynasty, had a stranglehold over the revenue and population of vast territories. They resisted the introduction of taxes by the tsar’s government and were tremendously resentful when Ivan sent his officials to collect those taxes, instead wanting to literally run things on their own – as they had done for centuries.

The old princely families were strong enough to resist Ivan's power. He was, after all, just the first tsar. His grand-grand-dad, Vasiliy II the Blind, was the first sovereign Moscow ruler. At this time, the country was full of people who hoped to restore the order of fighting duchies – or even to install themselves as tsars.

After more than 15 years of struggle between the tsar and the elites, in 1565 Ivan the Terrible made the most stringent decision – to divide the territory of his kingdom into two unequal parts – the ‘oprichnina’ and the ‘zemshchina’ (translated as ‘belonging to the land’). He invited to live in the oprichnina only those lands and nobles who swore personal loyalty to him. And everyone else automatically belonged to the zemshchina.

How did the oprichnina work?

"Ivan the Terrible and Malyuta Skuratov" by G. Sedov.

"Ivan the Terrible and Malyuta Skuratov" by G. Sedov.

The main problem was that the nobility did not serve in the military as they should have. The princes and boyars organized the Landed Army, which were feudally-organized fighting units of the Russian state. The different leaders fought each other for preeminence.

This defect was very noticeable in the course of the Kazan campaign. The noble warlords were constantly arguing about who was more noble, and who would obey whom. Instead of taking Kazan, they spent more time arguing! The tsar had great difficulty in resolving these disputes, and then he got tired of them. It was impossible to rationally command such an army!

The tsar created an army of oprichniks, inviting noblemen and princes to join; but not from Moscow. Rather, they came from ancient Russian cities – Suzdal, Vyazma, Mozhaisk and others. Most significantly, they were poor noblemen, with little or no land at all. Ivan ordered them to appear before him, and he questioned them about their relatives, service, and connections.

"Moscow during Ivan the Terrible's time" by Apollinary Vasnetsov, 1902

"Moscow during Ivan the Terrible's time" by Apollinary Vasnetsov, 1902

Even the key-keepers, bakers, butchers, grooms, and all servants who came to work in "oprichnina" residences, fortresses and towns had to be rigorously questioned. No one from zemshchina was allowed to be there. The result was that the oprichnina guards submitted only and personally to the tsar. The Moscow boyars and princes could not command them.

What did this private tsarist guard army do to subsist? The tsar simply took the best lands from the leading princes and boyars, and he had them evicted from their ancestral lands together with their families. Then they were granted lands elsewhere in the tsar’s realm, often far away from the noble’s original estate. This was done in order to weaken their power base. They were not given much time to pack, and they had to grab only what they could carry. This was the oprichnina terror to destroy the Moscow elite.

Those accepted into the ranks of the oprichnina swore an oath of allegiance: "I also swear not to eat or drink with zemshchina and have nothing in common with them," testified the Baltic Germans Johann Taube and Elert Kruse, who served in Moscow.

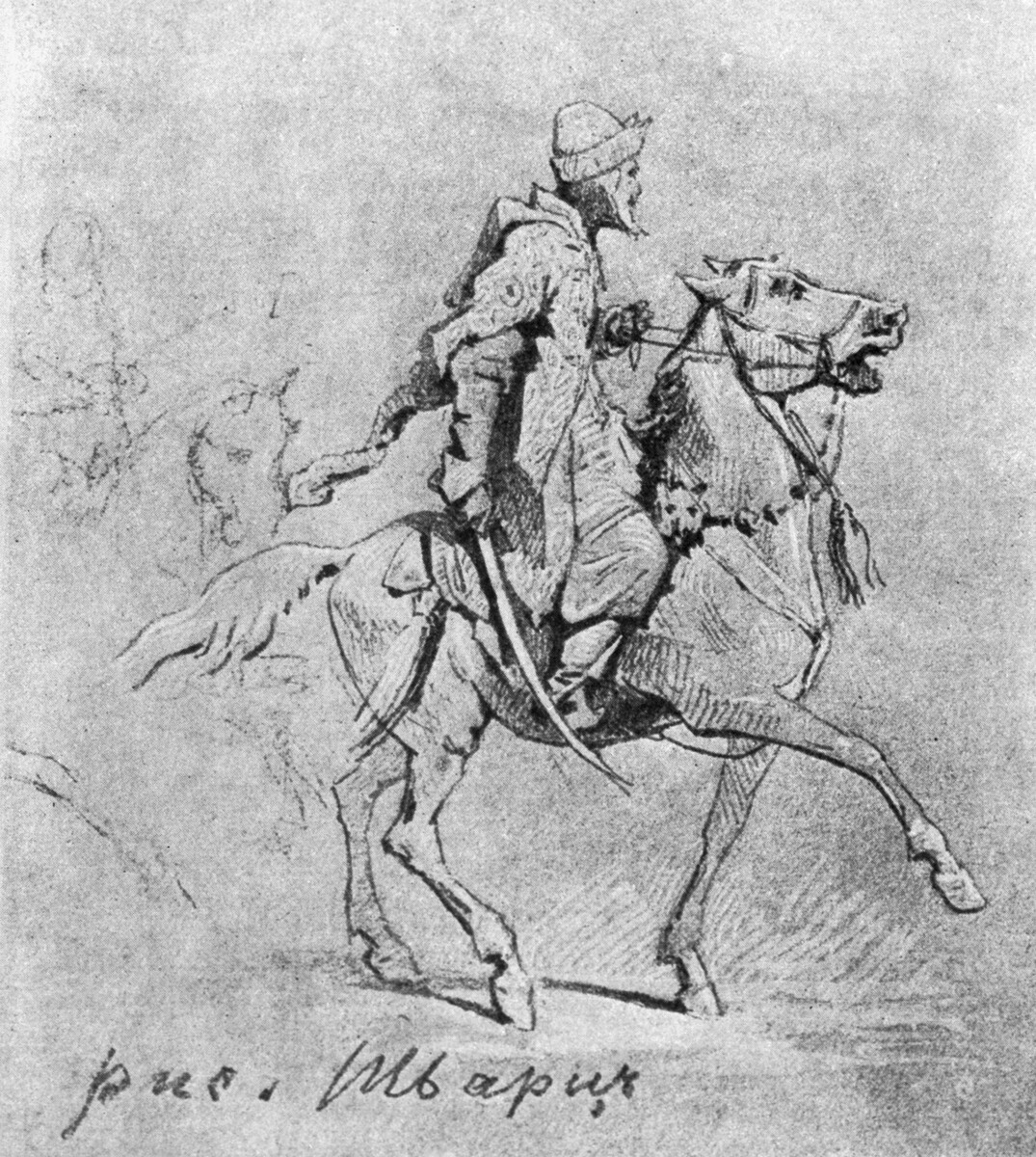

Oprichnik by Vyacheslav Schwartz, 19th century

Oprichnik by Vyacheslav Schwartz, 19th century

Another German in Russian service, Heinrich Staden, who was also an oprichnina guard, added: "According to the oath, oprichniks were not allowed to speak with zemshchina, nor to marry with them. And if an oprichnik had a father and mother in zemshchina, he would not dare to visit them at any time.” Compliance with these prohibitions was strictly enforced by oprichniks themselves: Staden wrote that if an oprichnik was caught talking with someone from zemshchina, other oprichniks killed them both on the spot.

Taube and Kruse write: "When an oprichnik and a person from zemshchina ... should meet, the oprichnik grabs the other one by the neck, takes him to court, though he has never seen him before or spoken to him, complains that he has disgraced him and the oprichnina in general; and though the tsar knows that this has not happened, the plaintiff is proclaimed a loyal man, and he receives all the estate of the defendant and the latter is beaten, driven through all the streets and then beheaded or cast into prison for life."

What did an oprichnik look like and where did he live?

The Alexandrov sloboda. An etching from the 17th century

The Alexandrov sloboda. An etching from the 17th century

"The oprichniks must have a known and conspicuous distinction when riding, namely the following: a dog's head on the neck of the horse and a broom on the whip. This signifies that they first bite like dogs and then sweep all the excess out of the country. The infantrymen must all walk in coarse beggar's or monk's outer garments on sheep's fur, but they must wear undergarments of gold-embroidered cloth on sable or goose fur," Taube and Kruse write.

Note that the horses of the oprichniks were fierce as well – not every horse could ignore a severed dog's head on its neck.

"All the brothers... must wear long black monk's staffs with sharp tips, with which one can knock a peasant off his feet, and also long knives under their outer garments, one cubit long, even longer, so that when one wants to kill someone, one need not send for executioners and swords, but have everything prepared for torture and execution," Taube and Kruse report.

Against the background of the 16th century Moscow boyars and nobles, who dressed very brightly – gold, scarlet and orange – the oprichniks in their black robes looked like monks. Oprichniks patrolled the streets of Moscow and other major cities in packs of 10-20 men. "Each individual pack marked the boyars, statesmen, princes and noble merchants. None of them knew their guilt, even less – the time of his death, and that in general they were sentenced," is how Taube and Kruse described the oprichnina terror.

Ivan the Terrible

Ivan the Terrible

Of course, not all of the 1,000 or 6,000 oprichniks belonged to the "order”, which consisted only of the most noble group of the oprichnina – between 100 to 300 people. They stayed with the tsar in Alexandrovskaya Sloboda (120 kilometers from Moscow) and truly lived like monks. Ivan assumed the role of their abbot, or hegumen.

Every morning at 4 o'clock, Ivan the Terrible rang the bells together with the sexton – Malyuta Skuratov, one of the most famous and cruel oprichniks. The entire "oprichnik court" immediately gathered in the church. Those who did not show up were punished with eight days of penance, regardless of their degree of nobility. From four to seven the tsar and the ‘brethren’ sang in church, then took a break for an hour, and from eight to ten continued the singing.

After that a meal followed: "He himself, as abbot, remains standing while those eat," Taube and Kruse wrote. Each brother must bring cups and vessels and dishes to the table, and everyone is served food and drink, very expensive and consisting of wine and honey, and what he cannot eat and drink he must take away in vessels and dishes and distribute to the poor; however, most of the time, this food was brought home. When the meal is finished, the abbot himself goes to the table. After he has finished his meal, he seldom misses a day, lest he should go to prison in which many hundreds of people are constantly kept."

After the day's affairs were completed, which often consisted of interrogations and investigations with torture, the tsar would go to the evening meal, which was combined with prayer and lasted until 9 o'clock. "After that he went to sleep in the bedroom, where there were three blind old men assigned to him," Taube and Kruse write. The blind men sang prayers and hymns to the tsar, as he drifted off to sleep. Thus ended the tsar's day in the oprichnina citadel.

How did the oprichnina end?

The bell-tower in Alexandrova sloboda that Ivan the Terrible allegedly frequented.

The bell-tower in Alexandrova sloboda that Ivan the Terrible allegedly frequented.

The oprichnina did not achieve its stated goals. The tsar failed to undermine the strength of the Moscow nobility and large landowners. In the end, he simply created an unruly force of noble bandits who primarily robbed the general population. According to research by historian Stepan Veselovsky, for each noble boyar or prince who the oprichniks killed, they also killed three to four innocent landowners; and for each one military man they jailed, at least 10 simple soldiers were killed. So, oprichnina guards mainly destroyed the weakest. And they themselves turned out to be really poor warriors.

In 1571, the Crimean Khan Devlet Giray attacked Moscow. The oprichnina, which had completely disintegrated by that time, were quickly scared and didn't come to defend the city. There were enough oprichniks for only one regiment, while zemshchina put up five. It didn’t help. Moscow was burned to the ground.

Ivan then decided to abolish the oprichnina. He had more serious problems: the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth won the Livonian War against Moscow, and the Swedes took a few castles and refused to return them. Ivan’s kingdom was heading for a most troubling time.