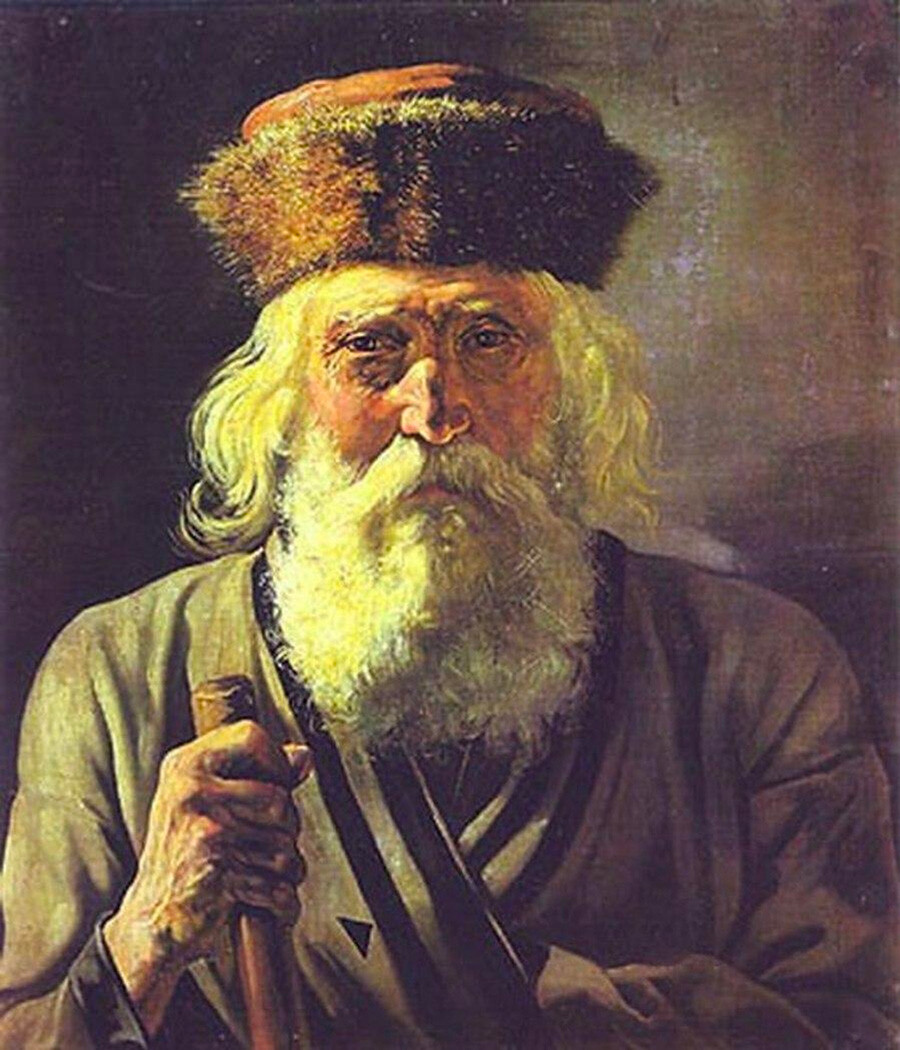

"Wanderer" by Vasiliy Perov (detail). Tretyakov Gallery.

Pavel Balabanov/SputnikChrist said, “If you want to be perfect, go sell your possessions and give to the poor, and you will have treasure in heaven. Then come, follow me.” Since the eleventh century, many Russian people began to follow this call literally. There were pilgrims to the Holy Land, as well as mere wanderers who left their homes and their families to – literally – endlessly wander the infinite expanse of Russia.

They wandered not only for religious reasons. In Russia the population had a high mobility from time immemorial. When the tsars introduced serfdom and military conscription, there were many people who in response to this "tightening of the screws" left everything and literally went wherever they wished.

Historian Sergei Pushkarev wrote: "In the Moscow state, there were still many free people who were not dependent and were not enrolled in the tsar's service, town or village communities.” As Pushkarev explains, these were the children of clergymen who had not become priests, children of civil servants who had not entered the service, children of serfs, hired laborers, wandering musicians called skomorokhs, beggars and vagrants who had not been given any land.

"Wayfarers. At the Volga," by Mikhail Nesterov, 1922

Private collectionIn Russia, wanderers were revered by society as folk saints. Wandering was something akin to the feat of the ‘holy fools’.

The Russian edition of the Brockhaus and Efron dictionary noted a wanderer as "a special type of beggar, sharply distinguished from the Western European beggar. A western beggar is in most cases mentally, morally and materially poor; here a beggar, especially in former times, was often a seasoned person, a welcomed person in every house where he or she entered, an interesting and inexhaustible narrator of ‘where he had been’.”

“A wandering beggar preacher, asserting the doctrine of Christ not by theological deductions, but by his own rags. Such an image was close and understandable to ordinary people," writes philosopher and researcher of Russian wandering, Daniel Dorofeev.

Since ancient times, wanderers have acted as a "living Internet", a kind of talking newspaper. It was the wanderers who could reach the illiterate and remote parts of the population and tell them the news about the latest Orthodox Church dogma, and the ordination of new hierarchs. Wanderers were often asked to pray for someone at holy places, place a candle, order a memorial prayer, and just pass a note to far flung areas, where most people would never go.

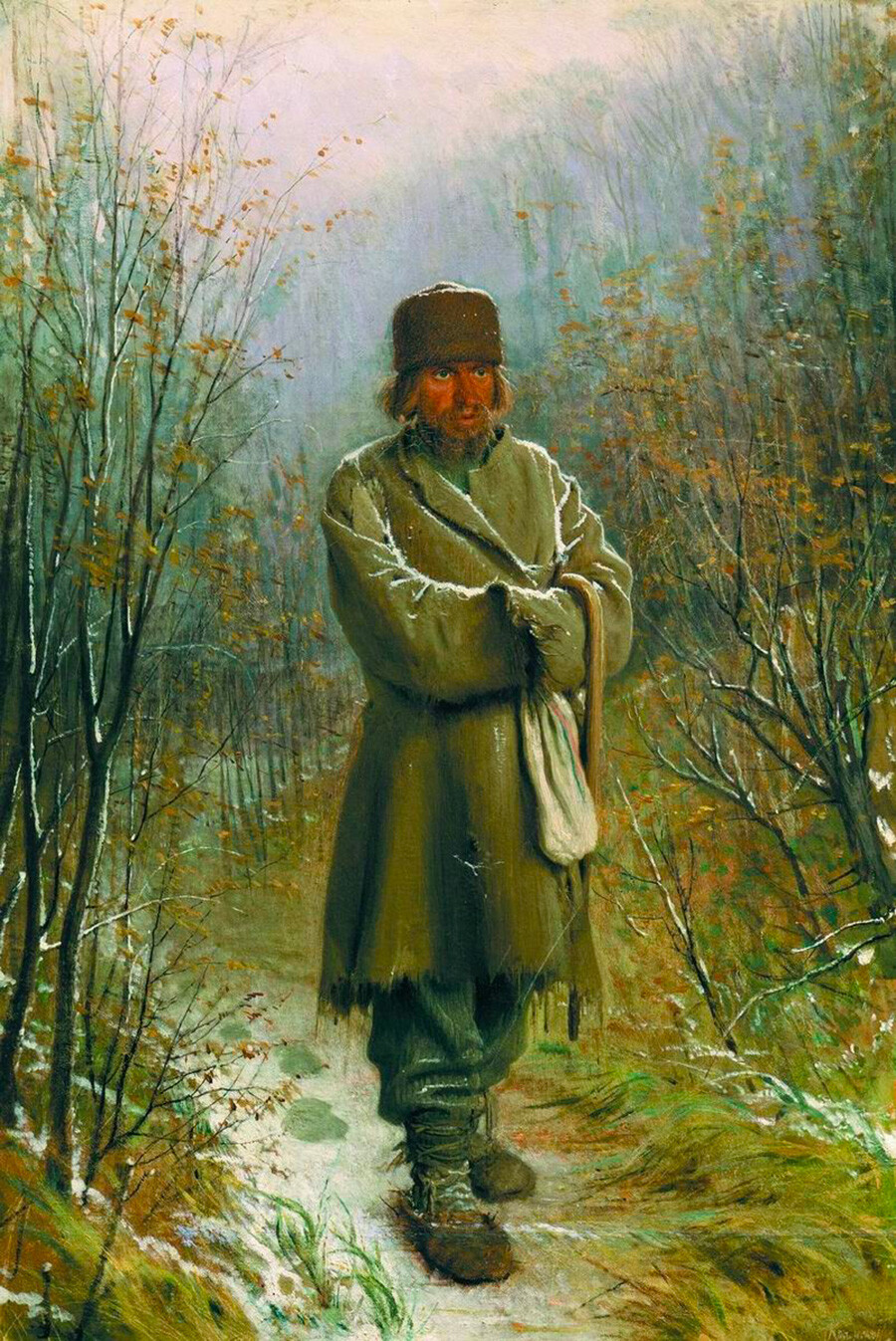

"Wanderer," 1870, by Vasiliy Perov. Tretyakov Gallery.

Pavel Balabanov/SputnikMany people, from church hierarchs to ordinary peasants, corresponded through wanderers, often using encryption! One could be confident that such correspondence would not be intercepted – amid the mass of identical wanderers, in their shabby clothing, it was highly unlikely that someone would be able to find a hidden letter. Such letters were often written in a secret script – "Tarabar script" – which was very popular among Russian priests. The mysterious Siberian elder Fyodor Kuzmich also corresponded secretly with his friends through wanderers and not one of his personal letters was ever intercepted by the police.

"Kalikas" by Illarion Pryanishnikov

Tretyakov Gallery1) Kalikas

“Kalika” was originally the name for a wanderer in Russia. Vladimir Dahl explains: "Kalika in the songs and tales, is pilgrim, wanderer, a hero in humility, in squalor and godly deeds.” In the 19th century, beggars who sang spiritual verses, songs, and psalms were all considered kalikas.

The kalikas wandered in groups, "artels". They had their own organization. An ataman stood at the head of the brigade, and in order to have the right to be called a real beggar, you had to be an apprentice for 6 years, paying 60 kopecks annually. You also had to pass a test in knowledge of prayers, kalika verses and songs, and a peculiar kalika language.

In such artels, there were even treasurers, as well as "sergeants" and "majors". Decisions in the brigade were taken at a general meeting, where all the chiefs were chosen and those who broke the rules were punished by "cutting off the purse".

"Wanderer," 1859, by Vasiliy Perov.

Saratov Art Museum named after A. N. Radishchev, Saratov2) Wandering storytellers and musicians

Вlind storytellers were often accompanied by a guide and often stood out among the cripples. They collected alms by singing spiritual hymns, reciting psalms, and sometimes accompanying themselves with a wheeled lyre, gusli, and domra. Blind old storytellers also visited the tsar's chambers. In the Alexandrovskaya Sloboda they read to Ivan the Terrible before going to bed. The wanderers who knew many stories and rumors were always welcome guests in the women's quarters of the 17th century royal palaces where separate dining and sleeping rooms were arranged for them in the first floors of the palaces.

"The Walk of the Cross in Kursk province", Ilya Repin, 1883. In the left part of the picture there is a group of wanderers.

Tretyakov Gallery3) Alm collectors

"Donate, good Orthodox people, for the church of God, for a stone building!" – such a cry has been heard for hundreds of years in all Russian streets and squares. This is the "proshak" (word derived from просить, prosit’, “to ask” in Russian), who is the one gathering funds for church needs. Note: the funds are for the church, not for his own needs.

Here is how the historian Sergei Maximov described the proshak: "Blue or black cloak, tightly wrapped and highly belted in a festive manner, with a claim to solidity and solemnity. The proshak is always elderly, invariably with a book, wrapped in black cloth, and on the last page is written a certificate of some church authority.”

"In wealthy places, in merchant towns and cathedral churches, there are long lines of such people, as many as a dozen," Maximov writes. Among the collectors were many nuns, who went with two girl apprentices who collected money; and monks, who always went alone.

"The Contemplator," by Ivan Kramskoy, 1876

Museum of Russian Art, Kiev4) Lonely wanderers

"I confessed my iniquities, repented, confessed, gave liberty to all the men who served me, and swore that I would torment myself for life with all kinds of labor and hide myself in a pauper's image... It is now 15 years since I wandered all over Siberia. Sometimes I was hired by peasants to do odd jobs, and sometimes I fed myself in the name of Christ. With all this deprivation, what a bliss, what happiness and peace of conscience I have tasted!”

These are the words of a noble prince, who became a wanderer. They are cited by the unnamed author of the book The frank tales of a wanderer to his spiritual father, which was very popular in 19th century Russia.

These wanderers were the most respected in Russia – those who consciously left their comfortable lives for the sake of wandering. Artist Vasily Perov described Khristophor Barsky, one such wanderer. "Tall in stature, but already bent, like the top branch of a tall fir tree, when in the midst of a warm winter it is covered with fluffy snow. His beard was not as white as the prince's, but rather gray, resembling the color of second-hand silver, but similarly trimmed; his eyes were sad, as if obscured by a black veil or time of long suffering... Instead of a cloak he was wearing a wide and patchy peasant caftan the color of rye bread, girt with a narrow belt with a brass buckle... And in spite of such an unattractive suit, in the whole figure of the old man, especially in his face, there was something inappropriate to his costume and his position.”

Anton Chekhov wrote of these people: "If you imagine the whole Russian land, what a multitude of the same tumbleweeds, looking for somewhere better, were now pacing the large and country roads, or dozing in the pubs, taverns, inns, on the grass under the sky, waiting for daybreak.”

"Vladimir highway," by Isaak Levitan, 1892.

Tretyakov GalleryThe people welcomed such wanderers with pleasure, for they admired their freedom and knowledge of the world and people. In them, in addition to personality, they saw the archetypal image of the Wanderer. "Wandering in Russia was a folk religion, and wanderers – folk saints; they were free from power – religious or state – they were close to the people, because they were not separated from it, constantly in front of it ... Everyone in principle left the opportunity to join these ideals, even to become a wanderer himself" wrote Dorofeev.

"Wandering women pilgrims," by Ilya Repin, 1878

Tretyakov Gallery5) Beggar wanderers

"As soon as he left the church the crowd of people rushed to him soliciting his blessing, his advice, and his help. There were pilgrims who constantly tramped from one holy place to another and from one starets (elder – RB) to another, and were always entranced by every shrine and every starets. Father Sergius knew this common, cold, conventional, and most irreligious type. There were pilgrims, for the most part discharged soldiers, unaccustomed to a settled life, poverty-stricken, and many of them drunken old men, who tramped from monastery to monastery merely to be fed.”

This is how Leo Tolstoy describes the most typical wanderers in the story Father Sergius. Not all wanderers were true believers and led pious lives. Fate pushed out on the road also ordinary people who resorted to almsgiving as a means of subsistence. They made up the great mass of wanderers, of whom there were hundreds and thousands at pilgrimage sites.

By the early 20th century, when Russia already built railroads and due to unprecedented mobility, such wanderlust by foot became a thing of the past. Still, Emperor Nicholas II and his family welcomed wanderers such as St. Basil the Barefoot or Paraskeva of Sarov, but they were well known and had many admirers, and they were already far from the old ideals, which was primarily characterized by anonymity. And then the interest of the imperial couple in wanderers faded immediately after the birth of their coveted heir.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox