"For Maria Ivanovna, with her extensive circle of acquaintances, getting out of Moscow for a long time was no walk in the park. It was necessary to say goodbye to everyone, so as not to offend anyone," wrote Dmitry Runich, a 19th-century civil servant, about his elderly aunt. "On Thursday at 6 p.m., Marya Ivanovna got into a carriage and went on visits, with a register in her hand; on this day she made 11 visits, on Friday before lunch – 10 visits, after lunch – 32, on Saturday – 10; altogether, a total of 63. “A dozen of the closest relatives,” she wrote afterwards, "were left for an appetizer.”

Two days later, reciprocal visits began: in one afternoon she was visited by princesses Golitsyna, Shakhovskaya, Tatishcheva, Gagarina, and Nikoleva; all one after another. She was struck with fear: ‘Well, what if the whole hundred should want to say goodbye to me!’, and she ordered her servant to answer that she was not at home".

"In a carriage near the Kremlin" by Rudolf Frentz (1888-1956)

Public DomainFor the Moscow and St. Petersburg nobility in the late 18th century, formal visits to relatives and acquaintances was often a daily duty. Departure and arrival to and from the city, birthday parties, big holidays, weddings and funerals – all these events required a formal visit. But that wasn’t the end of it; next, a return visit had to be accepted. To ignore this rule was to face the possibility of excluding oneself from decent society – one could expect not to be promoted in service or to find a favorable partner for marriage. Nobody would want to deal with such a boorish person who forgets to make and return visits.

This burdensome custom seemed wild to foreigners, and some, like Martha Wilmot from Ireland, were even "outraged" by it. Therefore, by the early 19th century, along with the fashion for all things English, the culture of visiting cards came to Russia and was eagerly embraced.

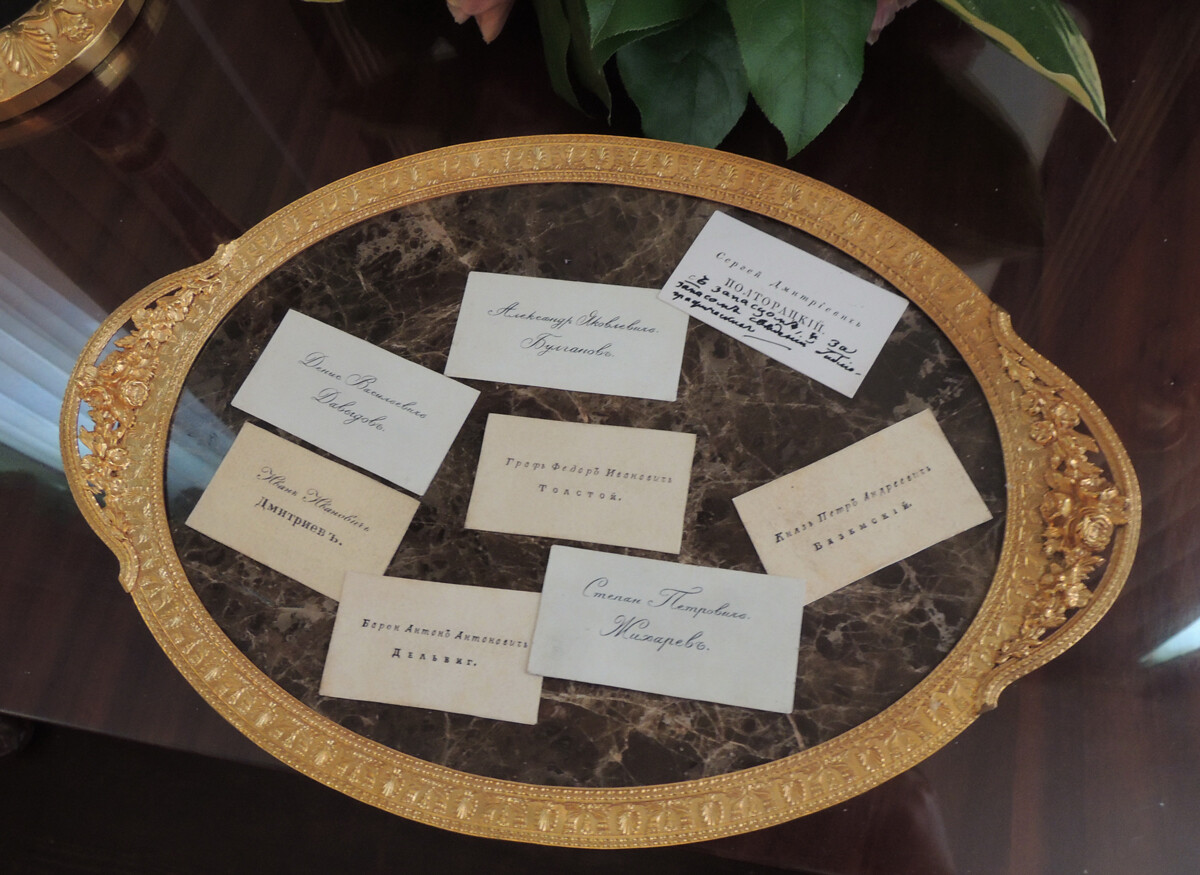

A marble tray for visiting cards.

Wikipedia / ShakkoSilver trays or expensive dishes for visiting cards were placed in the hallways and lobbies of Russian noblemen's houses – just like in London. Usually there were two of such dishes: one for the cards brought personally, the other one for the cards handed over through servants. After all, it made a big difference whether the visitor came himself or merely sent a servant. There were also unusual places for cards – in the house of one Moscow nobleman with a distinguished pedigree you could be met by a stuffed bear with its mouth open and a tray for business cards in its paws.

In the early 19th century, every noble gentleman and lady carried a pack of visiting cards (with their servants, to be precise). When arriving with a visit, they did not announce themselves at once – the butler came out, and he was handed a visiting card. Ladies' cards were larger and more intricately decorated. Men's cards were the usual size, about the size of a bank card or a pack of cigarettes, and the cards of married men were more modest and smaller than those of single men.

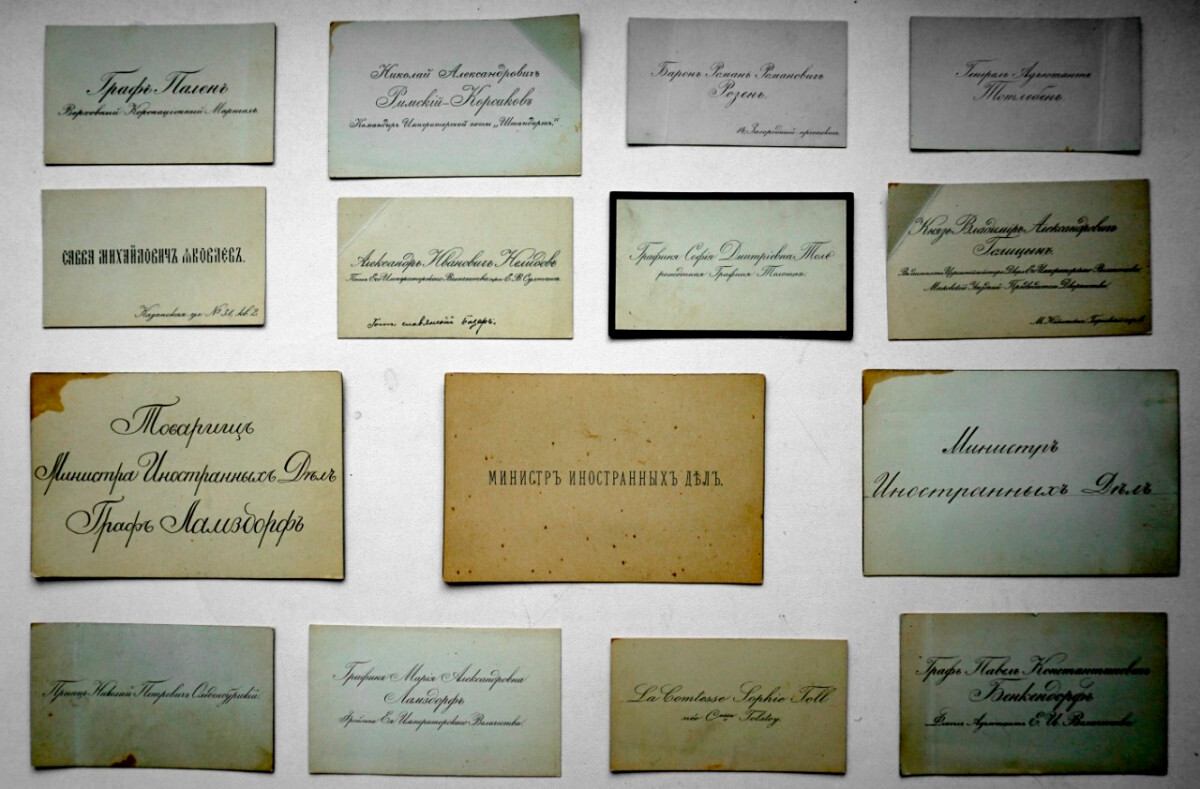

An array of Russian visiting cards from the 19th century

Ruza History MuseumThe name of the holder or owner of a card was written on it, as well as his or her title, rank, or position: doctors and scientists wrote "doctor" and indicated their degree, military men their rank, and civil servants their civil rank. Some people had two types of cards: one with an address, the other with a blank space on which they could write – to make an appointment, to invite to dinner or the theater.

Not everyone, however, kept up with the capital's rules. Moscow historian Mikhail Zagoskin recalled how his visitor did not indicate his address on the card: "I myself once happened to run around all the hotels to find out where the provincial who visited me lived. While I was looking for him all over Moscow, he had finished his business, left for his province, and now, as you can hear, is terribly angry, not only with me, but even with the whole of Moscow. ‘What a capital!’ – he says at every opportunity. ‘Polite’ people, I have to say, these Muscovites! Such ignorant, boorish folk!’”

There were moments in a nobleman's life when guests were totally unwanted. ("The New Cavalier" by Pavel Fedotov)

Tretyakov galleryIf the host was at home, the servant would bring the visiting card to him, and the host would decide whether to receive the guest or to cite busyness. If the host was not ready, the visiting ticket was left on the tray – just as when the host was not at home.

If the visit was to someone of higher rank or social standing, leaving a card was considered boorish. When servants came to visit a superior, or lesser noblemen visited a count or a prince, and the host wasn’t home or wasn’t receiving visitors, the butler wrote down the names of the visitors in a special book.

Poet Peter Vyazemsky recalled: "When Karamzin was appointed the state historian by Alexander I, he went to visit someone and said to his servant: "If I am not accepted here, then write me up at the butler." When his servant returned and said that the master of the house was not at home, Karamzin asked him, "Did you write me up?" – "I did." – "What did you write?" – "Karamzin, Count of History."

"Living room in the apartments of Countess Anna Sheremeteva on Boulevard Poissonnière in Paris," unknown painter, 1842

State Historical MuseumOf course, the old nobility despised visiting cards. Especially those brought by servants. "This is unlike anything: a serf arrives by my window in a four-horse carriage, and he throws a card on a tray of a Russian aristocratic woman," recalled Russian musician Nikolai Makarov, regarding the resentment of his elderly aunts.

Everything changed after the coronation of Nicholas I in September 1826. In their youth, Nicholas and his wife Maria Feodorovna used to be stars of European salons, and their coronation was attended by hundreds of French and English dandies, whose visiting cards were in full use and were not considered shameful. After that, the culture of visiting cards in Russia was finally established and persisted until 1917.

It was customary to make the first visit in person, and then subsequently one could personally write oneself up in the household’s registry, or leave a card. It was polite to reply to a card by sending a card. If no reply card was sent, or if it was sent, but wrapped in a paper envelope, it was a refusal, bordering on insult. A card in an envelope meant that it was better not to visit the house of the person who sent it.

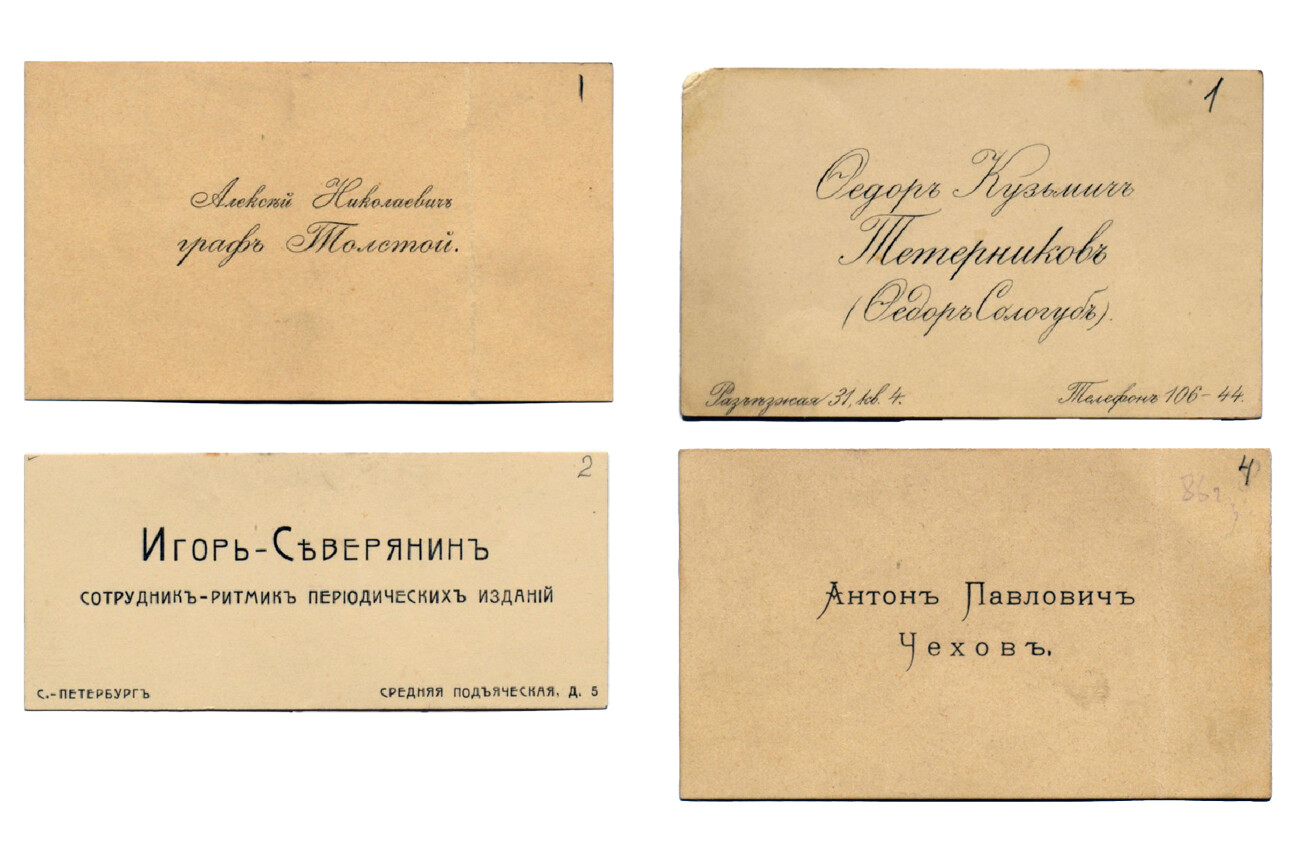

Visiting cards of Russian writers: Aleksey Tolstoy, Fedor Sollogub, Igor Severyanin, Anton Chekhov

Archive photoWhen a card was left without seeing the owners, it had to be "bent". Here's what these meant:

– "Came in person" – bent upper right corner.

– "Congratulations" – bent upper left corner.

– "Condolences" – bent lower left corner.

– "Goodbye" – bent lower right corner.

If none of the corners were bent, this meant that the card had been carefully passed along with the help of a servant. Of course, however, it wasn’t long before people began to send "bent" cards with servants. Prince Sergei Trubetskoy, who lived in the first half of the 20th century, recalled: "We usually left [our friends] in the evening, leaving the cards bent in advance to the doorman (and a ruble for tip), or one of us carried the bent cards of several friends and left them at certain houses: there was no custom of sending or leaving unbent cards in Moscow at that time.”

By the middle of the 19th century the custom of leaving cards, which was intended to maintain at least an appearance of politeness, had become an absolutely mechanical process performed by servants.

A view of Okhotny Ryad in Moscow

Public Domain"On New Year's Day and Holy Week there is the greatest consumption of calling cards," Mikhail Zagoskin recalled. "Footmen on coachmen, on horseback and on foot prowl all over the city. [...] However, the ‘card peddlers’ find a means to ease their labors; they have gathering places, the main one among them – in Okhotny Ryad; here, they compare their lists and exchange visiting cards. Of course, this is not always without mistakes. Sometimes you will be given the card of some gentleman, with whom you are not familiar at all, or a servant could involuntarily make you congratulate a person whom you would not want to meet."

Nevertheless, during the time of the Russian Empire a personal visit was certainly considered the most polite course of action to take in high society. Sometimes a simple card left or sent to a person of higher social standing could end the career of a hapless visitor forever.

Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox