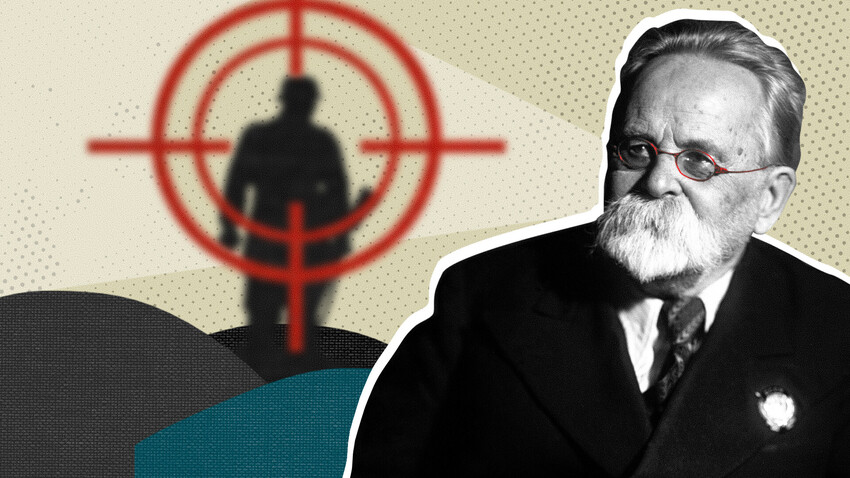

For several years now, a myth has been circulating on the Internet that the Russian revolutionary Nikolai Morozov (1854-1946) participated in the Great Patriotic War as a sniper and was the oldest combatant in the war. It is difficult to determine the source of this myth, but in the Russian segment of the Internet it is replicated not only by individual users, but also by popular newspapers and websites.

The myth is also very popular on the English web: the YouTube video outlining this tale has had more than a million views, there is a corresponding post on Reddit, and an entire paragraph is devoted to this myth in Morozov's biography on the English-language Wikipedia page.

It’s claimed that Morozov "took sniper courses in 1939... He shot accurately, despite wearing glasses, and once spent half a day lying in ambush in the snow before he killed a German officer. He used his academic training to enhance his sniper effectiveness by studying the flight path of his bullets and making adjustments for humidity and wind. A month later, he was recalled from the front line, despite his objections. A few months later, he unsuccessfully demanded to be returned to the front."

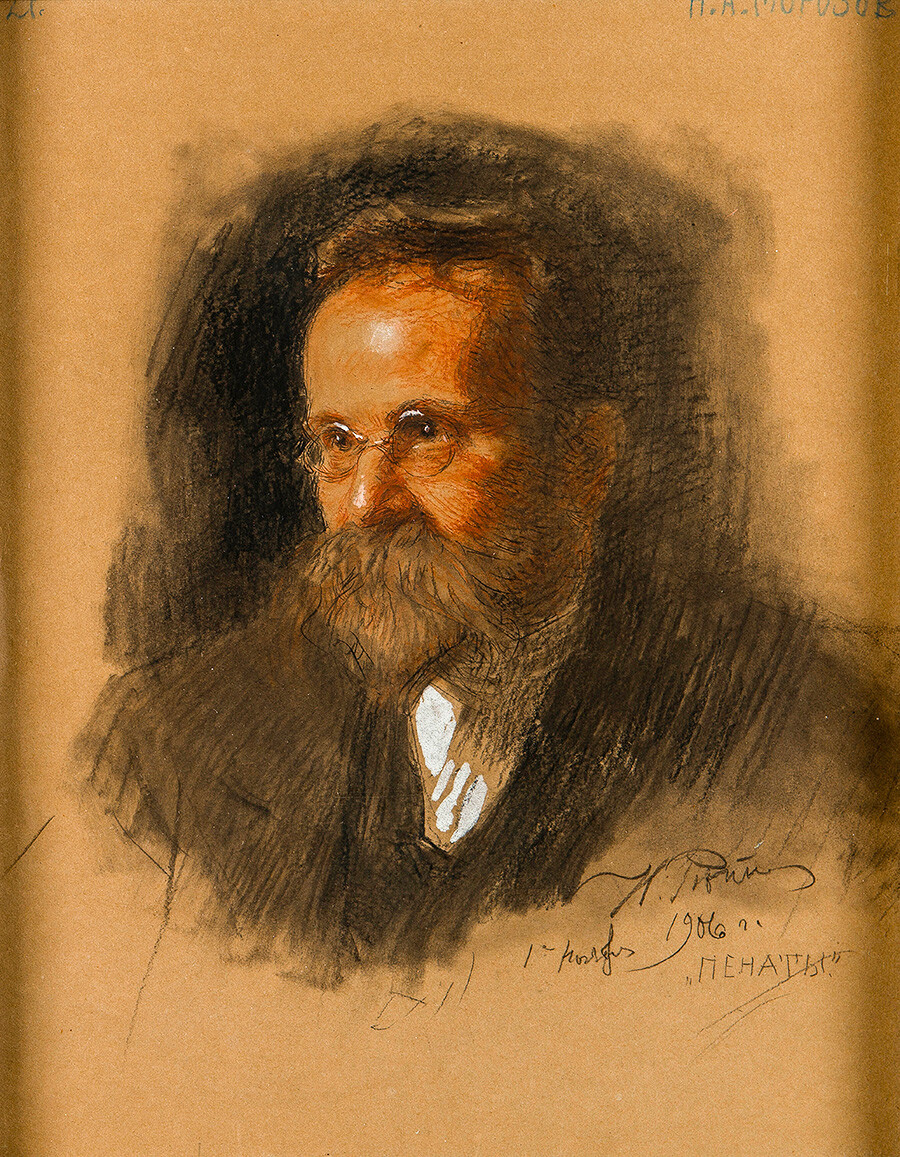

Portrait Of Nikolai Alexandrovich Morozov (1854-1946) By Repin, Ilya Yefimovich (1844-1930)

Legion MediaIn 1942, when Morozov allegedly joined the ranks of the Red Army, he was 87 years old, of which 24 years (1881-1905) had already been spent in prison. At this old age he was suffering from a number of chronic diseases. He spent the entire duration of the war at his estate, Borok, in the Yaroslavl Region.

In his book Nikolai Morozov: A hoax lasting a century, historian Anatoly Shikman cites a letter from Morozov to the chairman of the Leningrad City Executive Committee, Peter Popkov: "I myself have been on a long scientific trip for two years during the war with the permission of the People's Commissar of Education at the Scientific Research Hospital of the Academy of Sciences at Borok in the Yaroslavl Region, where I continue my scientific studies in astronomy and geophysics, with the exception of the winter of 1941-1942, which I spent in the Kremlin hospital due to ill health."

Another researcher of this topic, Maxim Lebsky, sent a letter to Natalia Nosova the director of the Nikolai Morozov Museum in the village of Borok (now Nekouzsky district of the Yaroslavl Region). In response, the director confirmed: "There are no archival documents about this. The museum has data, memories, and photographs that N. A. Morozov spent all the war years at his estate... He left only at the end of 1942 for prostate surgery (an airplane was sent for him from Moscow)."

Nikolai Morozov and his wife, pianist Kseniya Borislavskaya

Public domainThe real biography of Nikolai Morozov is quite amazing in itself. An illegitimate son of a nobleman from a peasant woman, as a young man Nikolai was carried away by revolutionary ideas and "went to the people", as the propaganda work among the peasants and workers of the Russian countryside was widely referred to. For a while, Morozov lived without property, on a fake passport, doing hard manual labor in order to earn his living. But his revolutionary efforts failed – the peasants and workers chased away the beardless boy with glasses lecturing them with his sermons about freedom. However, he got unwanted attention from the police who were not happy with his efforts to stir up the people. The result was his first three-year prison term, but when he was released in 1878, he continued revolutionary agitation. After the assassination of Alexander II in 1881, there were mass arrests of the Narodnik revolutionaries, and Morozov was caught crossing the Polish border.

When Morozov was positively identified, he did not deny that he was a "terrorist by his own convictions." In 1884, he was placed in the Schlisselburg Fortress, where he languished with 36 other revolutionaries. Considering their situation, they lived rather well – they lectured to each other, worked in the prison workshops, and ate regularly according to a schedule (unlike the majority of the Empire's population at the time). Morozov began to study science, especially chemistry, and, in his own opinion, he "made very far progress in studying the matter of the universe."

Morozov house museum in Borok, Yaroslavl region.

Yandex.MapsAfter the 1905 revolution, Morozov was released by a decree of Emperor Nicholas II that granted amnesty to prisoner. Two years later, he became famous in St. Petersburg by marrying the pianist Ksenia Borislavskaya, who was 26 years his junior.

Morozov quickly became a celebrity among the scientific and literary elite of St. Petersburg. In 1907-1911, he published more than 80 volumes, ranging from textbooks to poems. He became a member of the Russian Society of Physics and Chemistry, Russian Astronomical Society and an honorary member of the Moscow Society of Lovers of Natural Sciences. Morozov was listed as a teacher and professor of so many courses – world and physical chemistry, biology, and astronomy. It’s only unclear how he managed to focus on at least one subject.

However, when Morozov met the great scientist Dmitry Mendeleev in 1906 and presented his views on chemistry , Mendeleev was not impressed and did not accept his ideas. Experts, such as mathematician Boris Rosenfeld, were quite harsh and called Morozov's mathematical works "amateurish".

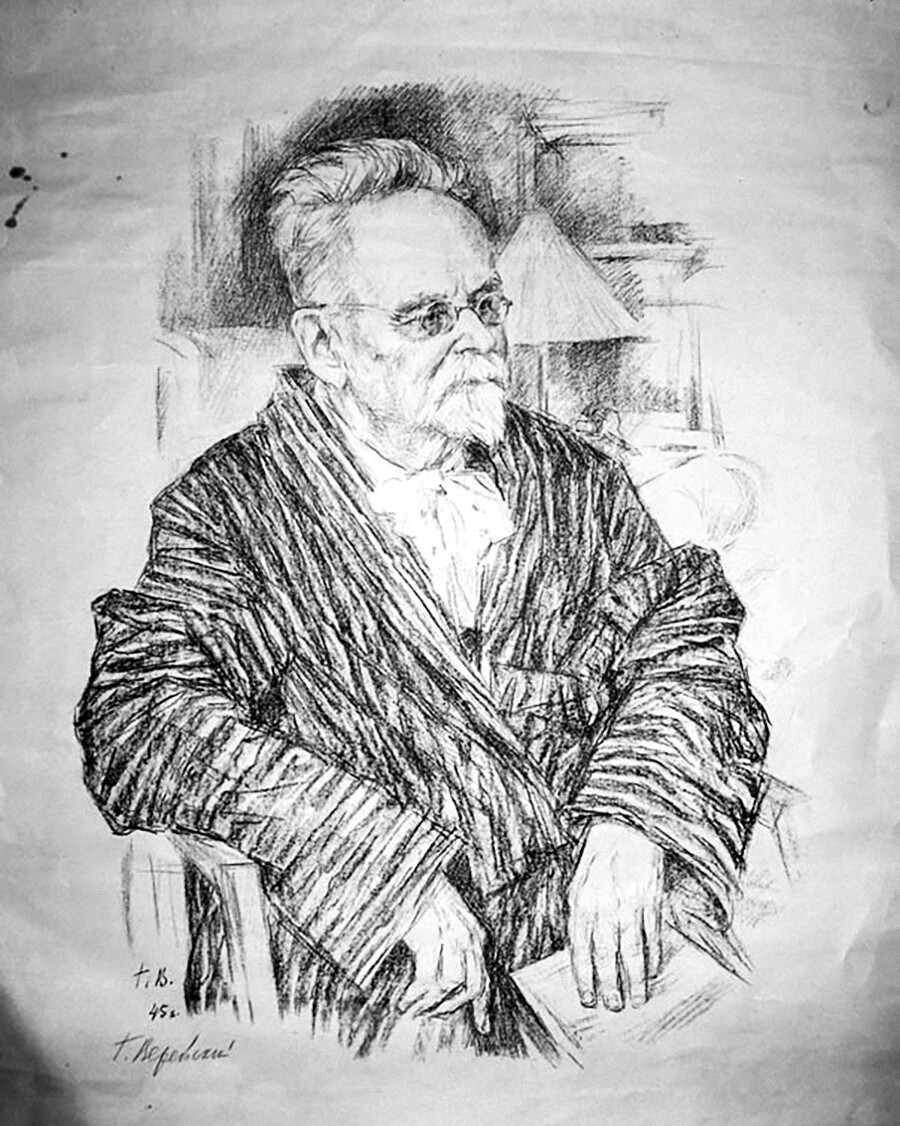

Portrait of Nikolai Morozov in his later years by G. Vereyskiy

G.Vereyskiy/Anatoliy Shikman, Nikolai Morozov: A hoax lasting a century, Moscow, 2016After the October Revolution of 1917, Nikolai Morozov managed to keep his estate in Borok. This was crucial for him, because it was a matter of survival as he had no other way to earn an income. He arranged that the Council of People's Commissars transfer the estate to him for life and exempt it from all state levies and taxes. For the rest of his life, Morozov continued to work in various positions in the USSR and constantly promoted his scientific works, including his pseudo historical research that was very controversial.

Morozov's study in his house in Borok

Nataliya Sergeeva/Yandex.MapsAccording to Morozov’s research, there was no history before the 1st century AD, at which time the wheel and the axe were invented. Then, in the second century, humans began to work with bronze and iron. His ‘research’ was published in a book that was titled Christ, in which he stated all his ideas. The book was more than 5,000 pages long and was published over the course of 1924-1932 on the personal order of state head of state security Felix Dzerzhinsky, and with the consent of Vladimir Lenin and Anatoliy Lunacharsky who was the People’s Commissar for Education.

The Bolsheviks considered Morozov a living communist legend, and they did not want to offend him in any way. However, Lunacharsky himself wrote about Morozov's book as follows: "Personally, I am familiar with the book. It is completely crazy, trying to prove on the basis of a ridiculous calculation [...] that Christ did not live in the first century, but rather in the fifth century, and thereby on the basis of this, denying the existence of such persons as Caesar and deeming that as myths..."

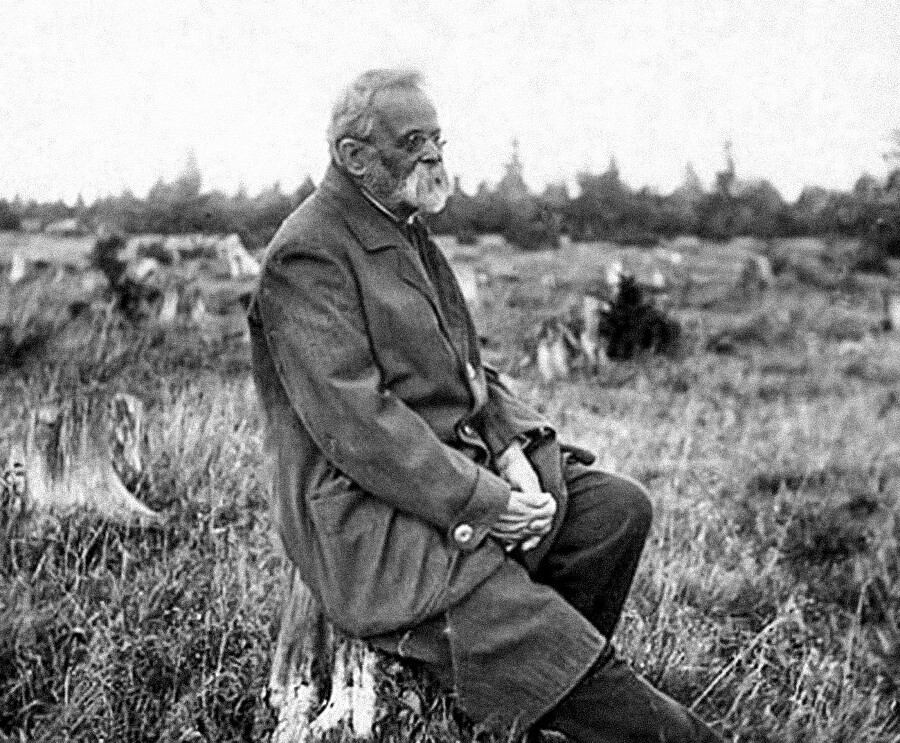

Nikolai Morozov in his later years, photo

Public domainLater, Morozov sought a meeting with Stalin, hoping to show him his work on the chronology of Russian history, but the Soviet leader refused to meet with him or read his works. At the same time, however, Morozov's birthday jubilees – 70 and 80 years – were celebrated with full state honors. In 1934, he became an Honored Scientist of the RSFSR. In 1944, while World War 2 raged, Morozov's 90th birthday was celebrated in Borok. Two years later, he died there in 1946.

Eventually, his controversial ‘new chronology’ was forgotten in the post-war Soviet era and today, his very odd research remains known to a few enthusiasts, simply as a bizarre curiosity of Russian intellectual history.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox