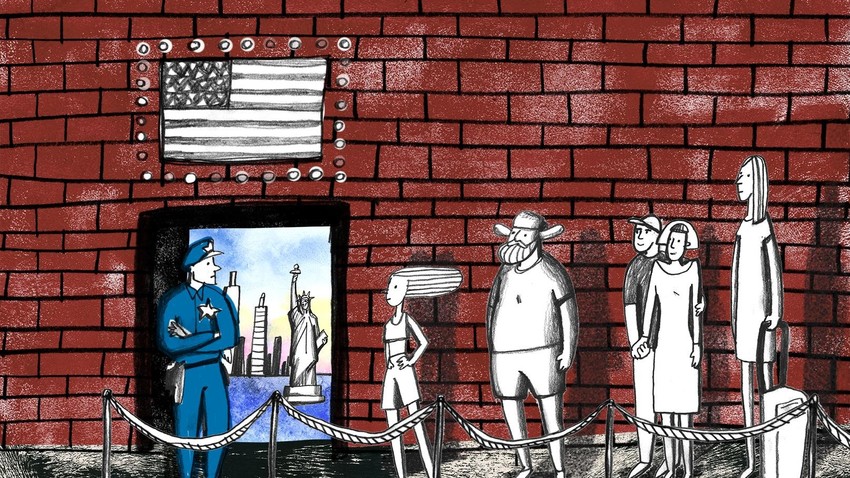

Dueling with bureaucracy: what Russians must (sometimes) go through to get an American visa

You never know if your interview for a visa is successful or not

Varvara GrankovaI read the badge, “Thomas Guard.” The surname precisely suited both the job of this tall, square-built man in uniform who I was talking to and his stern face. Mr. Guard was a visa officer in the U.S. Consulate and his job apparently was to reject every Russian trying to visit his country. At least he seemed to enjoy this.

“With such a guy – there’s nothing to hope for,” I thought while Guard was scanning me and my documents with his cold blue eyes. I even started habitually murmuring dirty Russian curses – a process I got used to trying to deal with the visa process. After all, the situation was messed up from the very beginning.

The very beginning

“What about you come to America in summer to visit? It would be fun,” Olga said two months before that, sitting in a café in the center of Moscow. She was an old friend; we went to the same middle school before she moved to the U.S., along with her mother, about eight years ago. Olga was doing well in her American life but visited the Motherland from time to time. Soon after we reconnected, she invited me to visit.

I only shrugged my shoulders to Olga’s question, however. America seemed too distant for me; it felt almost like she had offered me to go to the Moon or to Narnia.

A ten-hour flight, expensive tickets, paying a consular fee, and going through an interview where you can easily be rejected… So we changed the subject, and several days later Olga returned to the States.

“You are already late”

After a few weeks, in early May, I changed my mind. Visiting America with an almost-local guide and places to stay was an opportunity that only a complete idiot would pass up. So, we planned a nice 10-day trip including New York,

I embarked on my crusade against bureaucracy: read the list of things I needed for a visa and bought the tickets for July 1. The next day I told my boss, who visited America from time to time, that I’m going there in July. He enlightened me, saying that it was basically impossible.

“I’m afraid you can’t make it by July. It’s summer, the vacation season, so lots of people are applying for visas; there is a huge line in the embassy.” He was right: the U.S. embassy web page said that the nearest date for a visa interview was in early August. And I had to be in the U.S. in early July. Looked like the whole trip was going under.

A trip for a trip

After several hours of silent but very intensive cursing and some disappointed beers, an idea popped into my mind: why not go to another city? St. Petersburg had a U.S. consulate where you could also get a visa interview.

Today, you can’t because the U.S. suspended the work of all visa centers apart from the one in Moscow, starting August 23. But, at that time the waiting line in St. Petersburg was much shorter than in the capital, so I rejoiced and scheduled an interview for June 20. It seemed as if I could make it! But then another problem appeared.

US Consulate General in St. Petersburg.

Alexandr Galperin/RIA NovostiHow not to look like a migrant?

Before filling the form on the embassy website I read dozens of advice lists, “How to fill out a form and how to behave in an interview for a U.S. visa.” The more I read the more certain I was that there is no goddamn way of passing such an interview successfully.

Everyone was sure that it’s better if you’re not visiting anyone in the States –

On the other hand, however, lying was dangerous because I could easily get confused and mess everything up. I thought for several hours, cursed everything in the universe a couple more times and filled the form truthfully. “Power lies in the truth,” as the hero in the popular Russian movie, Brother 2, used to say.

Final stand

A month passed and here I was, standing in front of Mr. Guard. The trip that could have been over before it started, already cost a fortune: $690 for plane tickets, $160 for a consular fee, around $140 for roundtrip train tickets between Moscow and St. Petersburg.

The sense of disappointment, which descended on me as I answered Guard’s questions, was the worst. Manhattan’s skyscrapers, red-brick buildings of Boston, deep Atlantic Ocean – in my head all this was

The ending

I was so ready for rejection that began to think that not letting me into America was the completely right and appropriate thing to do. So when the mercilessly looking Mr. Guard, ending a chain of very brief questions, said, “Your visa is approved. Have a nice trip,” I almost shouted “What?! Are you out of your mind?!”

After quickly understanding that saying that wasn’t the best idea, I thanked the visa officer, who all of a sudden seemed a nice guy, and left the consulate feeling both happy and confused. I never understood his logic: about seven people, looking completely normal and far more responsible, were rejected right before me.

However, it didn’t bother me too much. All the efforts were (unbelievably) not in vain and a great trip was lying ahead of me.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox