Lost in the taiga: How the Lykov hermits became famous in the Soviet Union

Agafia Lykova, 2018

Iliya Pitalev/SputnikClothes made from hemp, shoes from birch bark and starting fires with flint. Dangerous wild animals in the summer, and freezing temperatures and waist-high snow in the winter; none of civilization's comforts, and the nearest populated area is 250 km away. This is how one Russian family lived for decades.

Agafia (center) and her father, Karp, 1982

kp.ruNearly 40 years ago, flying around the remote taiga in a helicopter, Soviet geologists spotted a vegetable patch in an uninhabited area in the upper reaches of the Abakan River. It turned out that the Lykov family – a father and his four grown-up children – lived in the forest. For many years these Old Believers had been cut off from the world, and then, thanks to a newspaper article, they became celebrities across the Soviet Union.

Agafia Lykova and journalist Vasily Peskov going across the Yerinat river, 2004

Vladimir Shelkov/TASSA few years later, in 1982, Vasily Peskov, a correspondent for Komsomolskaya Pravda, went to see the hermits. He expected to meet a family of five, but when he arrived, he found the father, Karp, his daughter, Agafia, and three fresh graves. Two brothers and their sister had recently died from illness, one after another. In 1988, the father died; (her mother had died of hunger in 1961). Only Agafia, who didn't want to change her way of life, remained in the forest.

Civilization’s harmful effects

Some people blamed Peskov for the Lykovs' deaths due to the shock of having contact with the outside world. The journalist was very upset by this because he had been trying to protect the Lykovs from the hordes that had rushed to the area to gape at them. For many years he had visited and helped the family by bringing kitchen utensils, medicines and even a goat, so that the hermits could have fresh milk all year round.

The cross on the grave of Karp Lykov, 2018

Iliya Pitalev/SputnikDuring one of his last meetings with Agafia, Peskov, who has since died, asked her whether it was good in her opinion that people had "discovered" the family. According to Agafia, God had sent people to them, and had it not been for these people, the family would have been dead a long time ago.

"What had our life been like before then? Our clothes were worn out and all covered in patches. It was terrible – we were eating grass and bark," Agafia said, according to KomsomolskayaPravda.

'Robinson Crusoes' of the taiga

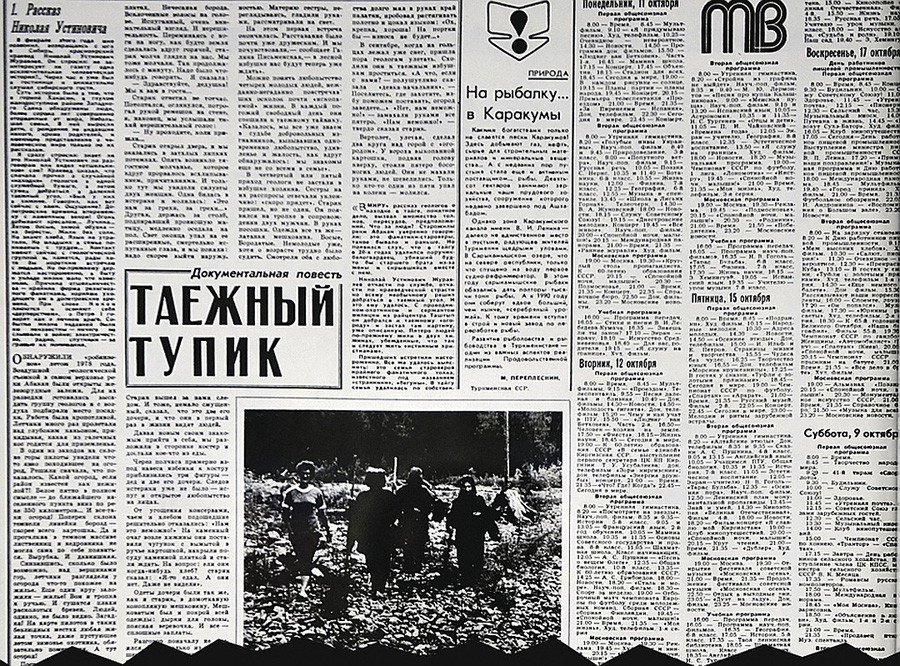

Following his meetings with the Lykovs, Peskov wrote a series of articles. The hermits' story captured the imagination of many people, and lines formed at newspaper kiosks every time a new installment about the Lykovs was published.

Peskov's report in Komsomolskaya Pravda newspaper

kp.ruPeskov told friends that each morning Brezhnev's wife would send a person to a newspaper kiosk to get the latest issue of KomsomolskayaPravda as quickly as possible because she couldn't wait to read the newest installment in the saga about the Siberian hermits. Later, Peskov's articles were published as a book, Lost in the Taiga, which was translated into many languages, including English.

Why the Lykovs moved to the forest

Over the centuries, many Russians fled and hid in the country's vast expanse because of their religious beliefs. The Old Believers had always been persecuted in Russia, and it was only Emperor Nicholas II who finally put a stop to it. After the Revolution, however, the Soviet authorities resumed religious persecution with a vengeance by forcing Old Believers to join collective farms, or putting them in jail.

The Lykovs' homestead in the Khakassky state nature reserve

Iliya Pitalev/SputnikFleeing collectivization, the Lykov family moved deep into the forest and found themselves in a state forest preserve. In the 1930s the authorities forbade them to hunt or fish.

Once, an anonymous accuser claimed that the Old Believers were poachers. The forest reserve guards went to check and accidentally shot dead the brother of Karp Lykov, but they told investigators that the Old Believers had put up armed resistance.

In 1937, the most terrible year of the Great Terror, the Lykovs were visited by people from the NKVD [the precursor of the KGB] who started questioning them in detail about the incident. The family realized that they had to flee. After that they started moving deeper into the taiga, always changing their abode, and covering their tracks.

Agafia – sole survivor

Agafia is now 74 years old, and for the past 30 years she has lived in the forest alone. Once, in 1990, she made an attempt to live with other people, choosing to reside in a schismatic priestless Old Believer convent, and even became a nun. Agafia's interpretation of the faith, however, turned out to be different, and she returned to her home in the forest. In 2011, representatives of the official Russian Old Believer Church visited Agafia and carried out a ceremony of baptism in strict accordance with church laws.

Lykov's family was originally priestless Old Believers, in 2010s Agafia was bapticized by the official Russian Old Believers Church

Iliya Pitalev/SputnikAgafia was given support by the local authorities, with Kemerovo Region Ex-governor Aman Tuleyev issuing instructions that the hermit be provided with all necessary help. Each year interest towards the lonely hermit only grows. Film crews, journalists, doctors and volunteers have been to see her.

In 2015, a British film crew headed by director Rebecca Marshall visited Agafia to make a documentary about her life, The Forest in Me.

Agafia sees solitude as the most important way to save one’s soul, but she doesn't consider herself to be lonely.

Agafia Lykova reads a letter form Bolivia

"Alongside every Christian there is always a guardian angel, as well as Christ and the Apostles," she says.

Read more: A life of a hermit aka 'The Hobbit of Moscow Region' in a forest (PHOTOS)

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox