Would the Russian people accept the return of the tsar?

The last emperor Nicholas II, his wife Alexandra, and their five children and five servants were all executed by Bolshevik forces on July 17, 1918. After being shot in a basement in Yekaterinburg, their bodies were thrown into an unmarked grave and burned. It drew a blood-soaked curtain over the centuries-old history of the Russian monarchy, and the question of restoration was shelved indefinitely.

But here’s the paradox. Even 101 years later, the last tsar is still popular. According to a 2018 poll by the All-Russia Public Opinion Research Center, the Russian public is more favorably disposed to him than to either Lenin or Stalin.

How many people want the monarchy back?

The result of the survey would suggest that Russians hold the monarchy in awe and reverence. But that’s not quite the case.

Those whose lives overlapped with Romanov rule are now so few in Russia that personal experience is definitely not a factor in current monarchist attitudes. “I've been fascinated by history since childhood, and not just in school. Gradually I came to believe in monarchism,” 18-year-old Alik Danielyan, a self-professed monarchist, told Russia Beyond back in 2017. Alik runs the “Monarchy Enclave” group in VKontakte (the “Russian Facebook”), with almost 14,000 followers.

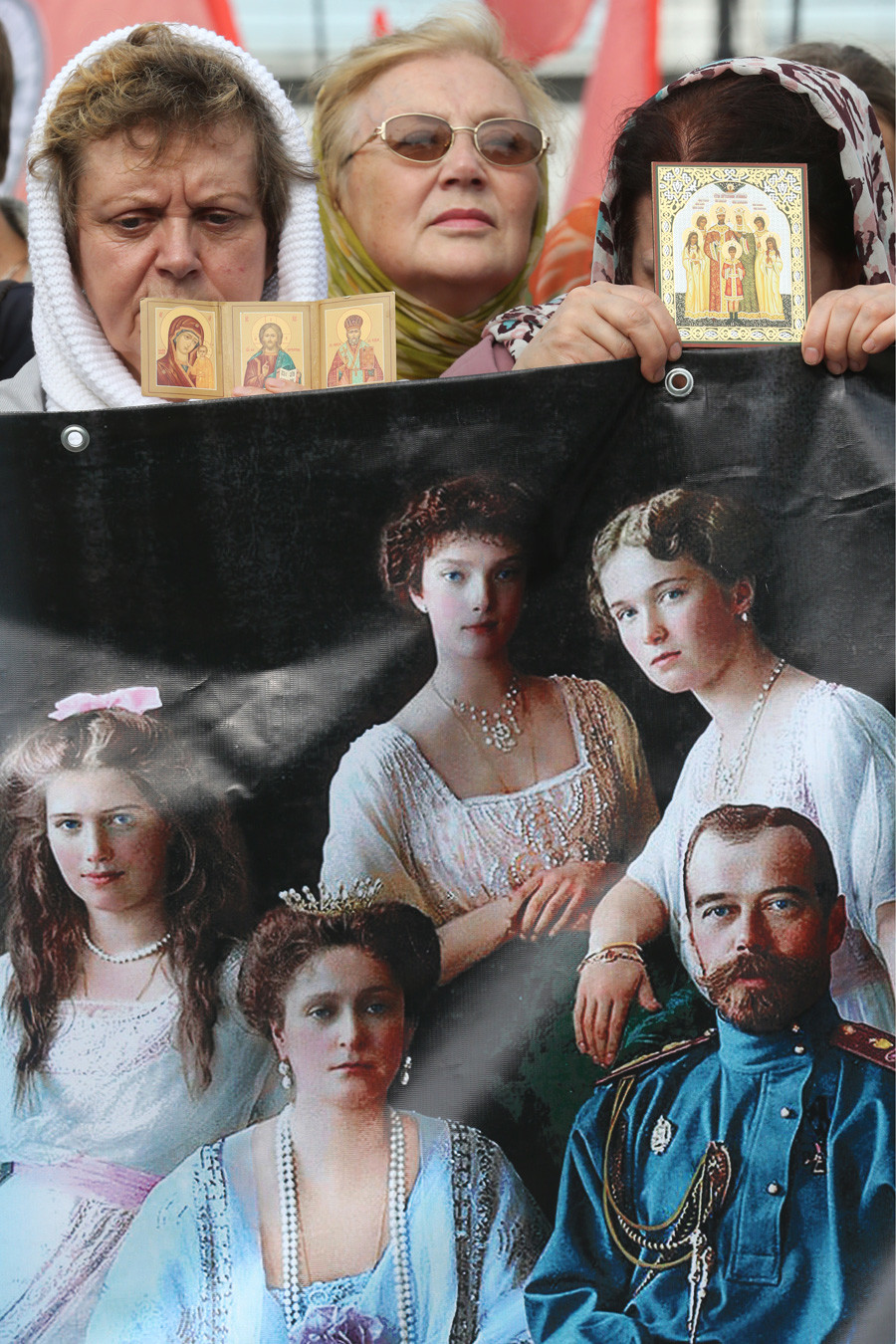

Protesters in Simferopol against the Matilda film

Alexandr Polegenko/SputnikIt was back then in 2017, the centenary year of the October Revolution, that the monarchy became a fashionable topic in Russia, and caused some heated arguments (though not quite as sparky as the ones in 1917). It had less to do with the actual centenary or the murder of the imperial family than with the pitched battles between Duma deputy Natalia Poklonskaya and the makers of the film Matilda about the love affair of Nicholas II with the ballerina Kshesinskaya (in the words of Poklonskaya, the film was “blasphemous” (since Nicholas II is now a saint) and “defiled” the royal family).

As shown by another poll, the likes of Alik in favor of restoring the monarchy make up 8% of the Russian population. For 19% of respondents, it depends on who exactly would wear the crown. And another 66% of all Russian citizens are categorically opposed to the return of the monarchy. As noted by political scientist Fyodor Krasheninnikov: “After 70 years of Soviet propaganda in Russia, the monarchy is still stubbornly viewed as an autocratic dictatorship, and not at all what is considered a monarchy in Europe.” Moreover, most Russians believe that the overthrow of the monarchy was “not a major loss” for the country.

What are Russian attitudes to the murder of the royal family?

The remains of the royal family were ceremonially buried in July 1998 (excluding Prince Alexei and his sister Maria, whose remains were discovered later and are in the Russian State Archive). The state funeral was attended by then President Boris Yeltsin, who described the massacre as “one of the most shameful pages in our history,” adding that the guilty parties were “those who committed this atrocity and those who justified it for decades afterwards.”

The opinion that the execution of the royal family was fair retribution for the mistakes of the emperor is held by just 3% of the Russian populace. In 2000, the Russian Orthodox Church canonized the murdered Romanovs as martyrs, after which an entire ritual of veneration and pilgrimage came into being. Churches were built on the sites of Ipatiev House, where the massacre took place, and Ganina Yama (“Ganya’s pit”) in Yekaterinburg, where the bodies were burned. In 2018, more than 100,000 believers came from all over Russia, as well as from Ukraine, France, Britain, the US, New Zealand, and elsewhere to pay homage. Many of them prayed all night, kneeling on the grass or directly on the asphalt. Some wept.

Read more: How the Romanovs lived out their last days

But how is all this relevant to monarchism today? Not at all, according to some historians. “In Yekaterinburg, where the largest events marking the centennial of the Romanovs’ deaths are being held, the Romanovs are martyred saints revered by devoted pilgrims, with virtually no reference to politics, policies, or ideology,” wrote Ala Creciun Graff, a PhD history student at the University of Maryland. Their canonization turned the Romanovs from political figures into religious ones, a symbol of faith. Moreover, one of the conditions for the canonization was that the Romanovs, as saints, should not be used in the political arena.

Where are the living descendants of the Romanovs?

Members of the Romanov family remain numerous to this day. Predominantly scattered across Western Europe and the US, they are mainly descended from the four sons of Emperor Nicholas I. The sister of the murdered Nicholas II, Xenia Alexandrovna, for instance, settled at Frogmore Cottage (not far from Windsor Castle), which is now occupied by Prince Harry and Meghan Markle. That said, even if the Russian throne still existed, none of the descendants of the Romanovs would have the right to claim it (here’s why).

Maria Vladimirovna in the interactive exhibition "Orthodox Russia.

Sergey Pyatakov/SputnikNevertheless, they often visit Russia, especially on the anniversary of the execution of the royal family, and remain apolitical, tacitly supporting Vladimir Putin. “It's a matter of principle for us not to partake in politics,” says Grand Duchess Maria Vladimirovna, the head of the Russian Imperial House of the Romanovs (a Swiss-registered organization that unites the majority of Romanov descendants). She also states that the House of Romanov is opposed to restitution, and asks for neither the return of any property that belonged to their ancestors, nor compensation from the state. Her son, Grand Duke George, held an official position at Russia’s Norilsk Nickel, the world’s largest metallurgical company, from 2008 till 2014, advising the CEO and representing the company’s interests in the European Union.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox