Who is Borgov from the latest Netflix show The Queen’s Gambit?

“There is one player that scares me. The Russian. Borgov,” says Beth Harmon, the chess prodigy in the new Netflix series, The Queen’s Gambit. The drama about a young orphan with drug and alcohol problems and an improbable talent is built around the story of her chess career in the 1960s. Her rivals are all men, the main one being a Soviet luminary, World Chess Champion Vasily Borgov. He is focused and economical with his emotions, prefers the classical school to intuitive play and in general appears solid and monolithic compared with Beth’s other opponents. He is the world’s best player. At least initially.

The Queen’s Gambit is a completely invented story and there isn’t a single real chess player among the American challenger’s opponents. Still, the protagonists do have fairly closely-matching prototypes. Including Borgov, of course. So who is the real figure behind the fictional Soviet grandmaster?

Boris Spassky

The most likely candidate is Boris Spassky, the 10th World Chess Champion and twice USSR champion. Chess enthusiasts immediately spotted the similarities in Borgov’s characteristic features and tactics. Spassky was famous for his endgame technique and baffled his opponents with his favorite ‘Closed Variation of the Sicilian Defense’ (Beth is told about these “pitfalls” as she is preparing for her match with Borgov). Like Borgov, Spassky was famous for his standoff with an American - in real life it was Bobby Fischer, the legendary “rock star” of chess. Their encounter in 1972 was popularly dubbed the Soviet-U.S. “Match of the Century”.

Bobby Fischer, right, and Boris Spassky play the last game of their rhistoric 1972 "Match of the Century," in Reykjavik, Iceland.

APSpassky began playing chess at the age of five in an orphanage where, with his brothers, he lived for a time during the war years. After the war, the boy started going to the chess pavilion in the park, spending all day there like a person possessed. In just one year, he achieved a Class A ranking, becoming the youngest holder of the classification in the country. “One of the problems of youth chess is the enormous emotional pressure. I used to come home and literally collapse. And the next morning, without fail, I would be late for school,” he recalls.

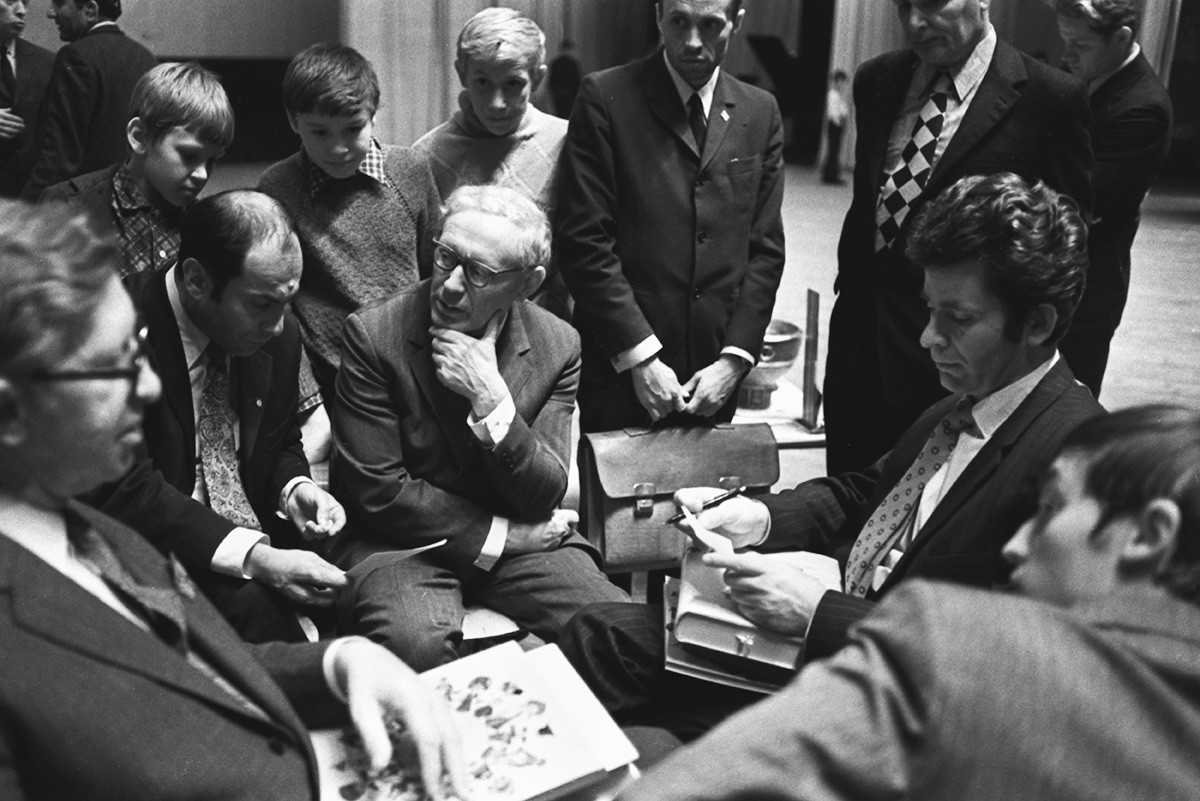

Vasily Smyslov, Mikhail Tal, Mikhail Botvinnik, Boris Spassky, and Anatoly Karpov (L-R) discuss a chess game.

Viktor Velikzhanin/TASSAt 18, he became what was then the youngest grandmaster in history and in 1969, aged 32, he took the crown at the World Championship, defeating Tigran Petrosian. By then Spassky had already played Fischer on many occasions and defeated him. As in the Netflix story, he drove his opponent to tears: “Matches with Fischer were nervous and tense. I think Fischer even cried after a game at that time,” he says.

And another allusion: That “Match of the Century” between Spassky and Fischer for the title of World Champion in 1972 was supposed to have ended in a draw. The Soviet Sports Committee was insisting on it, reminding Spassky that the country’s reputation was at stake and not just his personal ambitions. But Spassky took risks and made a mistake. When Fischer won, Spassky joined the audience in applauding him - exactly as Borgov did in his final match with Beth Harmon.

That contest was the peak of Spassky’s career. He never succeeded in defeating Fischer at tournaments again. He received a fee of 93,000 dollars for the match, with which he bought a Volga M 21 luxury car and soon moved to France - he was never forgiven in his own country for his defeat and the authorities refused to pay for his trips to tournaments. “Invitations for me to take part in international tournaments would arrive, but the Sports Committee decided to take revenge on me for losing to Fischer,” according to the chess player. “Moving from Moscow to Paris allowed me to take part in all the international tournaments. It was the only reason I changed my place of residence.”

His career continued for another 20 years, after which Spassky returned to Russia and applied himself to popularizing chess in the country. He is now 83 and lives in Moscow.

Anatoly Karpov

Soviet Grand Master Anatoliy Karpov competes in the European Chess Championships.

Getty ImagesKarpov resembles Borgov to a lesser degree than Spassky does, but, as is stated in the foreword to the eponymous novel by Walter Tevis (which the series adapts for the screen), the author took inspiration from these three great chess masters - Spassky, Fischer and Karpov.

This comes as no surprise as Karpov was the best chess player in the world for a decade from 1975. He also had the reputation of being the leading chess-playing Communist. His confrontations with opponents frequently ended in a furor, with accusations flying around of psychological pressure and of the involvement of parapsychologists during matches. Viktor Korchnoi (four-time USSR champion who fled the Soviet Union and settled in Switzerland) wrote in his book that he used to put on sunglasses “to deprive Karpov of his favorite activity: to stand at the table looking his opponent straight in the eye. While I was wearing glasses, he could only see his own reflection.”

Read more: How Russian chess players used psychic powers against each other

Grandmaster Anatoly Karpov.

Dmitry Donskoy/SputnikKarpov started playing at the age of four, taught by his father, a military engineer. In 1963, as one of the country’s most gifted young chess players, he was admitted to the Botvinnik School, run by the patriarch of the Soviet chess school. At the time, Mikhail Botvinnik said about the young Karpov: “I’m very sorry, but Tolya is going to get nowhere.” But he was very wrong. Subsequently, Karpov was to become the 12th World Champion and collect nine Chess Oscars during the course of his career (the award was given for the most successful chess player of the previous 12 months). His style of play could be described as a calm, unhurried, but solid advance, without abrupt attacks, leaving no opportunity for counterattack. The very “Soviet school” that Beth Harmon is so afraid of.

After the famous 1972 defeat of Spassky by Bobby Fischer, Karpov became the main Soviet chess hope. He didn’t, however, manage to take on Fischer: The American refused to play (which was automatically counted as a defeat) after the International Chess Federation failed to meet his terms for the tournament. Karpov spent almost two years conducting unofficial negotiations to get the match to take place after all, but nothing came of it. Karpov became the only world champion in history who not only received his title without playing a world championship match or tournament, but did not play a single game with the preceding champion. He subsequently demonstrated his legitimate claim to the title on numerous occasions at various tournaments.

World Chess Champions Anatoly Karpov (left) and Boris Spassky (right).

Vladimir Fedorenko/SputnikAdditionally, during all these years, Karpov combined his chess career with other pursuits. He got a degree in economics 10 years later, in 1978, while already World Champion, but he made good use of his academic qualifications. Aside from a political career (USSR Supreme Soviet deputy and State Duma deputy for the ruling United Russia party in several convocations, including the present one), he has also been a banker and businessman and was president of the company, Berghoff-Russia. Today, Karpov mainly concerns himself with politics and particularly ethnic issues. He is also regarded as one of the most famous philatelists in the Commonwealth of Independent States - his stamp collection is believed to be worth at least 13 million euros.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox