Reproduction of Boris Kustodiyev's "Fair" (1908). The State Tretyakov Gallery.

Yury Artamonov/RIA Novosti

Street food has always been an interesting part of life in Moscow. 100 years ago, a walk to the market or a ride into town didn’t take long, and there were plenty of options for people who wanted to grab a quick bite to eat. They didn’t have modern fast food back then though. So what did people in pre-revolutionary Russia eat?

Blini (Russian crepes)

Who on a cold day would refuse hot rosy blini with sweet filling? No one! That is why blini were the main type of street food offered by vendors. Such vendors could usually be found in particularly lively places around the city, such as Okhotny Ryad, Solyanka and near banyas, markets or train stations. The prices were the same everywhere. It was also possible to grab a quick bite to eat not only at the street stands but also in some taverns. In his collection of stories about Moscow, Vladimir Gilyarovsky wrote that a popular place serving blini was the lower hall of the Nizok Tavern. The blini there were baked from morning to night and prepared right in front of the customers.

Kalachs and barankas (rolls and bagels)

Magic lantern (Volshebny Fonar) magazine

The kalach is the oldest type of white bread in Russia. In Moscow, the kalach looked like an iron weight because its lower part was round and soft, while the upper part resembled a hard handle made out of dough. People would hold onto the handle while eating the kalach but did not generally eat the handle itself, which was thrown away or given to the poor. The reason for this is that it was not always possible to wash your hands before eating a kalach, and so people held the handle to keep the edible part from getting dirty.

Kalachs were sold at malls on narrow trays. Usually they were sold frozen so that they would stay fresh for longer. Then when a customer bought a kalach, it was defrosted with a hot towel and, thanks to the special qualities of the dough, it did not taste much different from a freshly baked one.

Barankas appeared later than kalachs. They were first mentioned in a 1725 decree by Peter the Great that their price. Mass production in factories only began in the second half of the 19th century. The baranka was a ring of dough boiled in water and served as a type of Russian dessert. They were baked and kept on a string, several dozen at a time. They were particularly popular at fairs and on national holidays.

Grechniviks

Grechniviks had a special place in the world of street food. Even Gilyarovsky wrote about how they were sold in Okhotny Ryad. They were also popular during Lent before Easter, when Orthodox believers refrained from eating fatty and sweet foods. The grechnivik resembles a flat omelet made from buckwheat porridge and is quite easy to prepare. The porridge would be heavily boiled, placed into a pan and then cooled. Then slightly whipped eggs would be poured over the grechnivik, which would then be fried on both sides using vegetable oil. Vendors sold grechniviks right off the trays and served them in melted vegetable oil. They were popular among coachmen waiting for their next client.

Pirozhki (pies)

Magic lantern (Volshebny Fonar) magazine

Hot pirozhki were mostly served as snacks accompanying kvass, but, being the cheapest type of street food, they were also in high demand among students. Pirozhki bakers would walk around selling them in a box covered with a special little cushion that kept them warm. In Moscow, they were prepared with all sorts of fillings, including jam, potatoes, eggs and even liver. Pirozhki with jam were sold for five kopecks each, while those with meat cost twice as much.

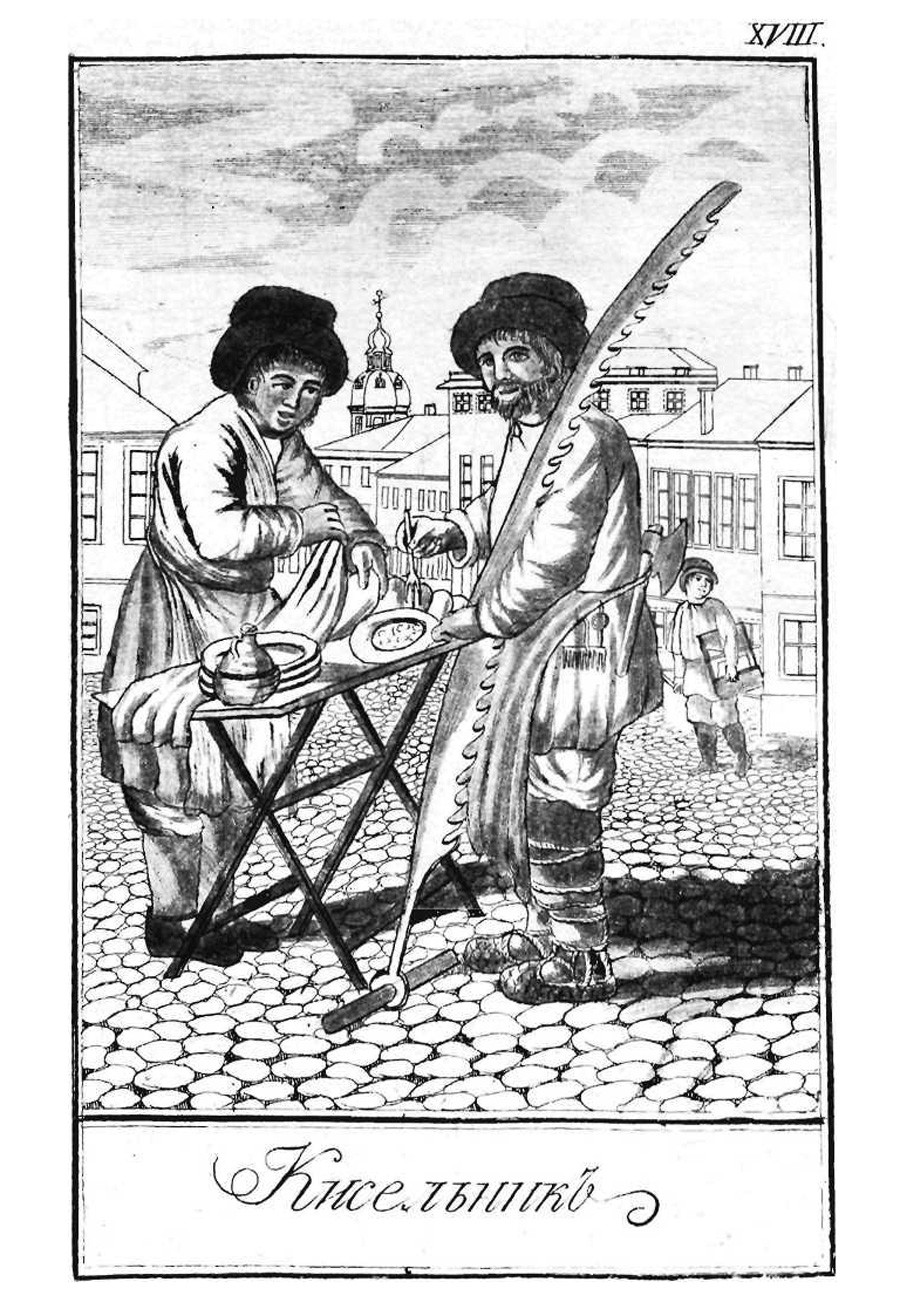

Gorokhovy kissel (pea jelly)

Pea kissel is another type of Lenten food. It is even easier to prepare than grechniviks. Pea flour was mixed with boiling water, left in an oven for 15-20 minutes and then poured into a mold to cool. When ready, it could be cut into pieces. It kept its shape but was not particularly attractive in terms of presentation: a yellow-green jelly cut into slices and swimming in butter. Nevertheless, Muscovites loved it. On particularly strict days of Lent, an even more modest type of kissel made from oats would pop up. It was prepared in the same way only using oat flour and was served without butter.

Schi (cabbage soup)

The most expensive street food in those days was schi, a traditional Russian soup made of sour cabbage, potatoes, ham and a rich meat broth and served with sour cream. One pot cost 10 silver kopecks, and merchants at the market could order it without even leaving their stand. The vendor, flying like a bullet through the market, would hand out pots of the hot soup to clients and then return some time later would to collect the dirty pots and clean them with a rag.

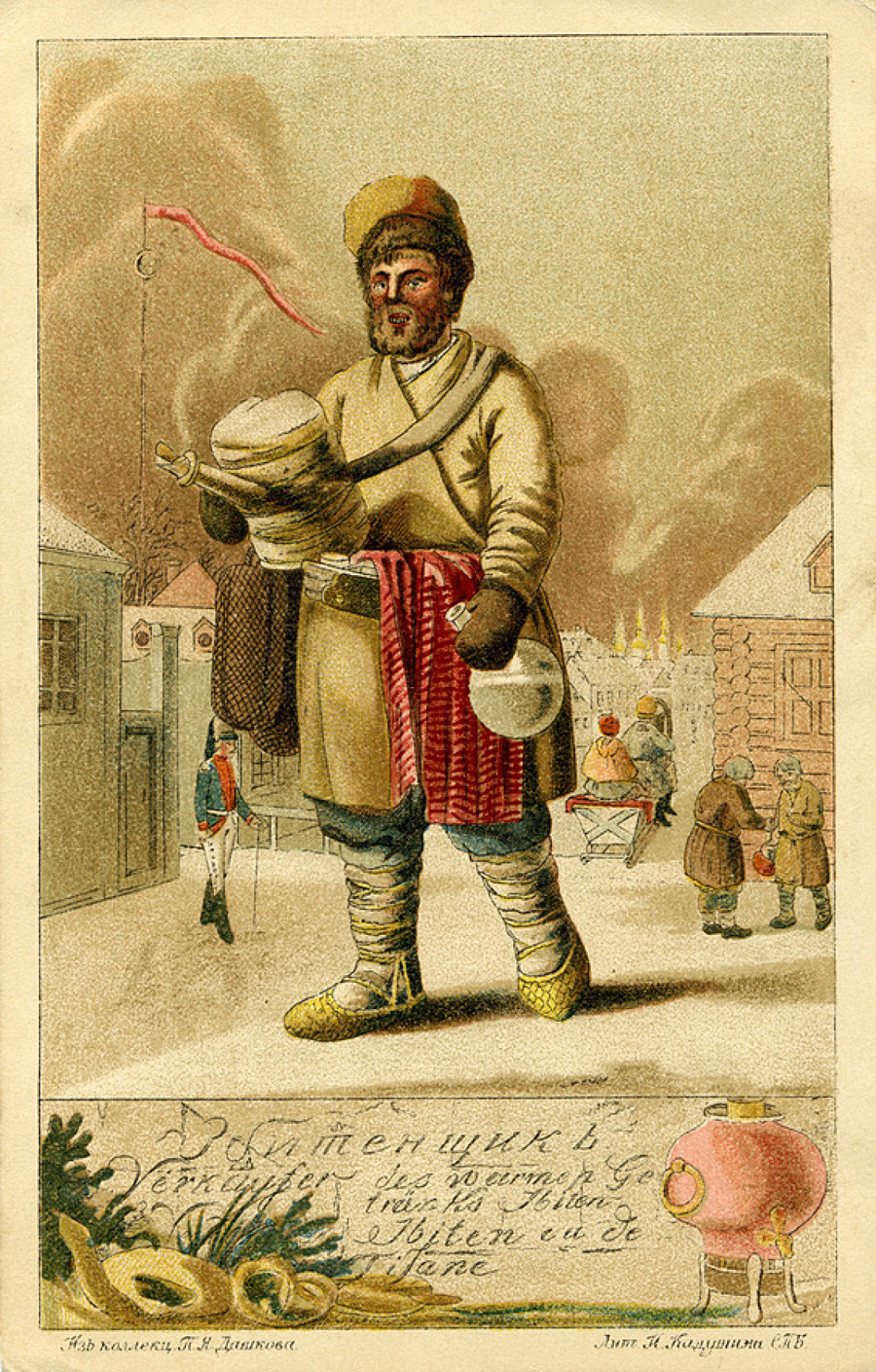

Sbiten

Russian winters are known for being harsh, but there were always lots of national holidays and winter festivities that brought people out to the streets. No one wants to freeze while outside, and so hot drinks were always in high demand. Sbiten is a kind of traditional Russian honey drink. People who sold it were called sbitenschiks. In Moscow they were mostly found near Kitai-gorod and Okhotny Ryad, the neighborhoods with the most vibrant markets. It was generally poured into containers that had narrow necks designed to prevent the drink from cooling too quickly.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.