As in other countries, chocolate was not immediately beloved in Russia.

Asya ChoAccording to one version, in the early 18th century, hot chocolate was brought to Russia from Europe by Emperor Peter I. The nobility immediately disliked the beverage made from cocoa beans, calling it a “witch’s potion” and “soot syrup”. Perhaps that is why another version, associated with the name of Catherine II, appeared.

According to it, hot chocolate appeared in St. Petersburg in the late 18th century with the help of Venezuelan ambassador Francisco de Miranda. It was presented to Catherine the Great’s favorite, Prince Potemkin, who highly appreciated the hot drink. Records have survived of Potemkin drinking coffee and eating chocolate five or six times a day in an odd combination of ham or chicken. The Empress must have liked chocolate, as well; the court began to order cocoa and chocolate took roots in Russia, though it remained very expensive (and still only popular in drink format) and was only available to high society.

Ambassador Francisco de Miranda.

Public domainLieutenant-General Konstantin Stackelberg, who was head of the emperor Alexander III's court orchestra, noted in his notes in the late 19th century that “at the Imperial Court, after meals, a cup of chocolate was served in addition to coffee”, a custom that had survived since the reign of Catherine II.

It was not until the 19th century that cheaper cocoa powder and beet sugar became available and then the drink became more affordable. In 1818, a visitor to St. Petersburg wrote to Moscow about a store on Nevsky Prospect (the main street in the city), where “it is pleasant to relax and have a cup of hot chocolate”.

Dinner in the Palace of the Facets, Moscow.

Mikhail ZichiChocolate began to appear in literary works by Dostoevsky, Gogol and others. For example, writer Ivan Turgenev, in 1872, described the serving in the story ‘Spring Waters’ this way: “…a huge porcelain coffee pot filled with fragrant chocolate, surrounded by cups, decanters of syrup, biscuits and rolls, even flowers.”

The recipe for hot chocolate of that time is written in a popular cookbook from 1861 titled ‘A Gift for Young Housewives’ by Elena Molokhovets: “For three cups of milk, take 50 to 100 grams of chocolate. You can grate it or break it into pieces, boil it together with milk, often stirring, pour it into cups and serve sugar separately. Sometimes, a spoonful of heavy whipped cream is also put into such chocolate.”

About 600 chocolate factories opened in the second half of the 19th and early 20th centuries. By 1914 (the beginning of World War I), there were 170 chocolate factories in St. Petersburg and 213 in Moscow.

The Einem confectionery factory in the 1900s.

Public domainEinem’s factory: In 1851, Ferdinand Theodor von Einem, a German entrepreneur (a national of the state of Württemberg), who, in Russia, took the name ‘Fyodor’, opened a chocolate and a small confectionery store on Arbat Street in the center of Moscow. The enterprise turned out to be successful and, in 1867, he was able to build a factory on Sofiyskaya Embankment. Production increased significantly and, by 1871, half of Moscow’s candy was being produced under the direction of Einem and his German partner Julius Heuss. During the year, 32 tons of chocolate, 160 tons of chocolate, 24 tons of tea cookies and 64 tons of broken sugar were produced.

Boxes for chocolates and cookies made at the Einem's factory.

Dmitry Korobeinikov, Ekaterina Chesnokova/SputnikBuyers loved not only the taste of the candy, but also the tin boxes in which they were sold. The particularly expensive ones were finished in velvet, leather, silk and gold embossing. There was also a surprise waiting for the customers in the box. Together with the candy, they received free notes of the mock ‘Chocolate Waltz’ or ‘Cupcake Galop’.

‘Clumsy Bear’.

Public domainOne of the most famous candies was the ‘Clumsy Bear’ (“Mishka Kosolapy” in Russian), which was first made in 1913 and it still enjoys great popularity. The picture of the wrapper repeats the plot of the famous painting by Ivan Shishkin ‘Morning in a Pine Forest’.

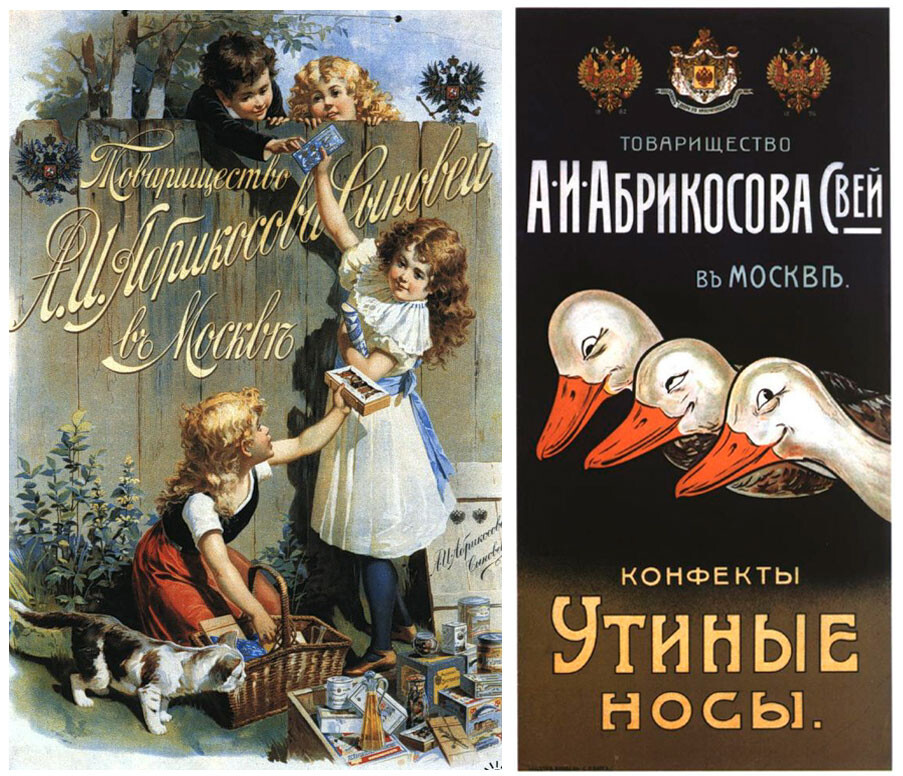

Abrikosov and Sons Factory: Russian chocolate history and the reorientation of chocolate products towards children is connected to the name of Alexey Abrikosov. And it's no accident - he and his wife had 22 children. In Spring 1879, trade house ‘A. I. Abrikosov and Sons’ bought land in the area of Sokolniki in Moscow for a confectionery factory. In 1880, ‘Factory and Trade Association of A. I. Abrikosov and Sons’ was established.

Candy wrappers designed at Abrikosov's factory.

Public domainAbrikosov was the first in Russia to cover dried fruits with chocolate glaze; earlier, they had been imported from abroad. In 1899, they became the biggest success: the Apricot company became the supplier of the Court of His Imperial Majesty and was allowed to put the Emperor’s coat of arms on the label. The factory was the first to produce ‘Goose Paws’ candy (at that time they were called ‘Goose Noses’). By the beginning of the 20th century, about four thousand tons of caramel, candy, chocolate and biscuits were produced there.

The French family Sioux: In 1855, a French couple Adolphe and Eugenie Sioux opened a small confectionery store with handmade chocolate candy in Moscow. Subsequently, their sons continued their parents’ business and, in the 1880s, founded the ‘S. Sioux and Co. Trading House’ and built a factory. They produced solid chocolate, caramel, nougat, marshmallows and marmalade. Sioux brand stores appeared in major cities across the country.

Bolshevik Factory, formerly owned by the Sioux family.

Public domainInitially, the Soviet authorities’ attitude to chocolate was negative, as it was considered a delicacy of the bourgeoisie. Meanwhile, this did not prevent the production of inexpensive candy with images of the new Soviet leaders on the wrappers. Nonetheless, chocolate was not considered a basic necessity, and the food situation in the country was dire.

After the revolution, the Einem and Abrikosov factories were nationalized and, in 1922, they were renamed the Red October Factory and the Babayev’s Factory (named after the chairman of the district executive committee). Most of the small factories were closed. The Sioux family left the country and their factory was also nationalized.

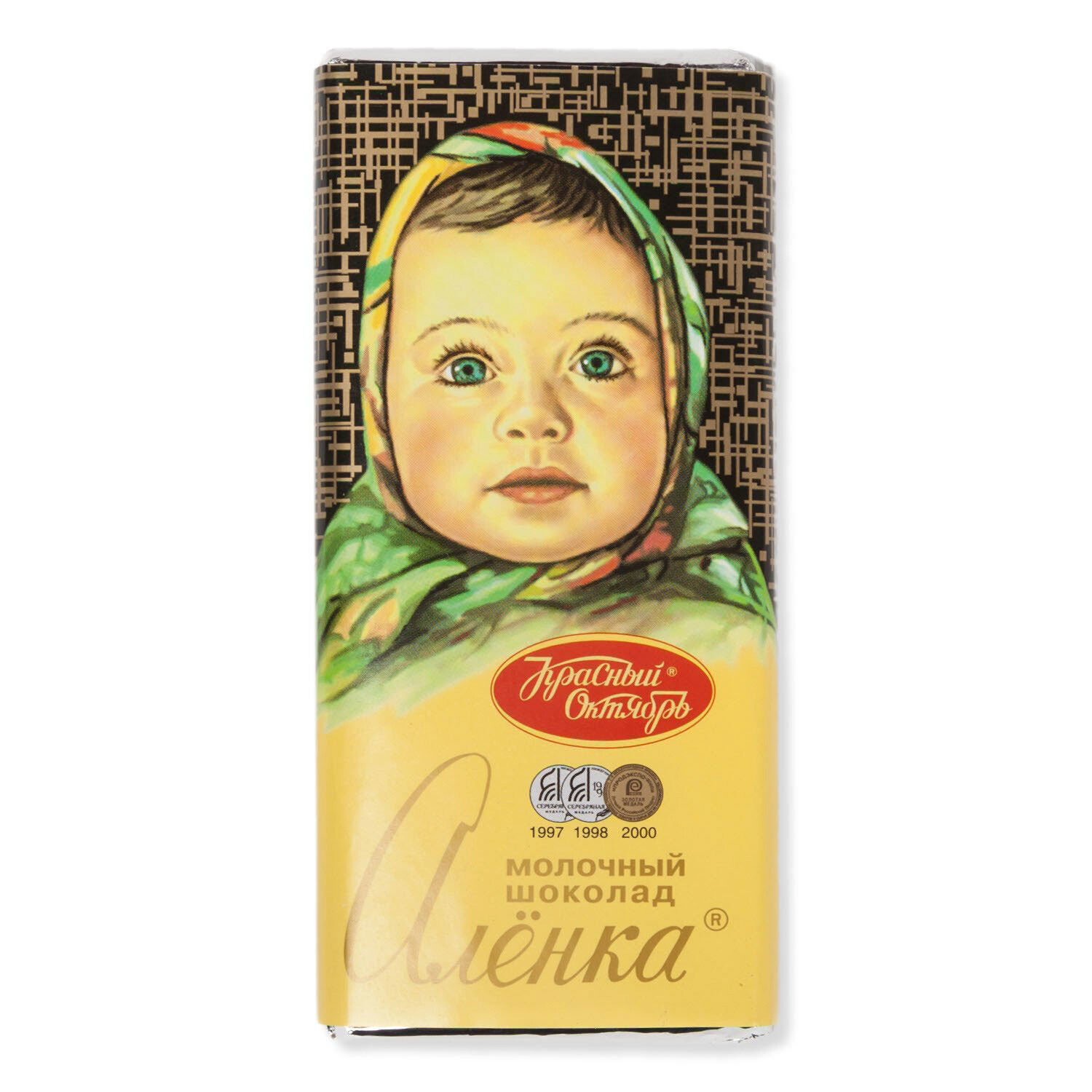

Russian milk chocolate 'Alionka'.

Public domainThe Soviet government’s attitude to chocolate changed by the middle of the 20th century. The government instructed the factories to produce milk chocolate candies that would be available to Soviet citizens.

In 1946, Babaev’s factory began producing the first chocolate bars in multicolored foil in Russia. In the 1960s and 1970s, the factory created new varieties of chocolate and candy. The most famous among them were ‘Babaevsky’ and ‘Vdohnovenie’ (‘Inspiration’) chocolates. Around the same time (1966), Krasny Oktyabr factory released a chocolate bar with a blue-eyed girl in a scarf on the wrapper and called it ‘Alenka’, which then later would become famous worldwide.

Today, Krasny Oktyabr and Babaevsky factories, together with a dozen other chocolate factories, are part of the large United Confectioners holding company.

Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox