How Russia fell in love with Napoleon through candy, cake, and booze

“If the spirit of Napoleon, whom poets have revived so many times, was really resurrected and was to walk around Moscow, that Moscow which one hundred years ago met him so inhospitably, he would now be pleased with the city. Everywhere you see his portraits and busts, books dedicated to him, his image on postcards and various trinkets, Napoleon candy, Napoleon perfume. Plays and operas are being written with him as protagonist. Not to mention the cinema,” wrote the Russkiye Vedomosti newspaper in August 1912. Russia was celebrating the 100th anniversary of its victory over the French in the War of 1812 and vendors cashed in as the public’s appetite for sweets and booze ballooned.

A sweet emperor

The 100th anniversary of the conflict and Napoleon’s retreat from Russia was a real success for confectioners. In Moscow, St. Petersburg, and other cities people developed a serious sweet tooth for chocolate and “Emperor” caramel. For example, the Georg Landrin factory in St. Petersburg, which specialized in pastilles, produced sweetmeats in the form of the famous Corsican.

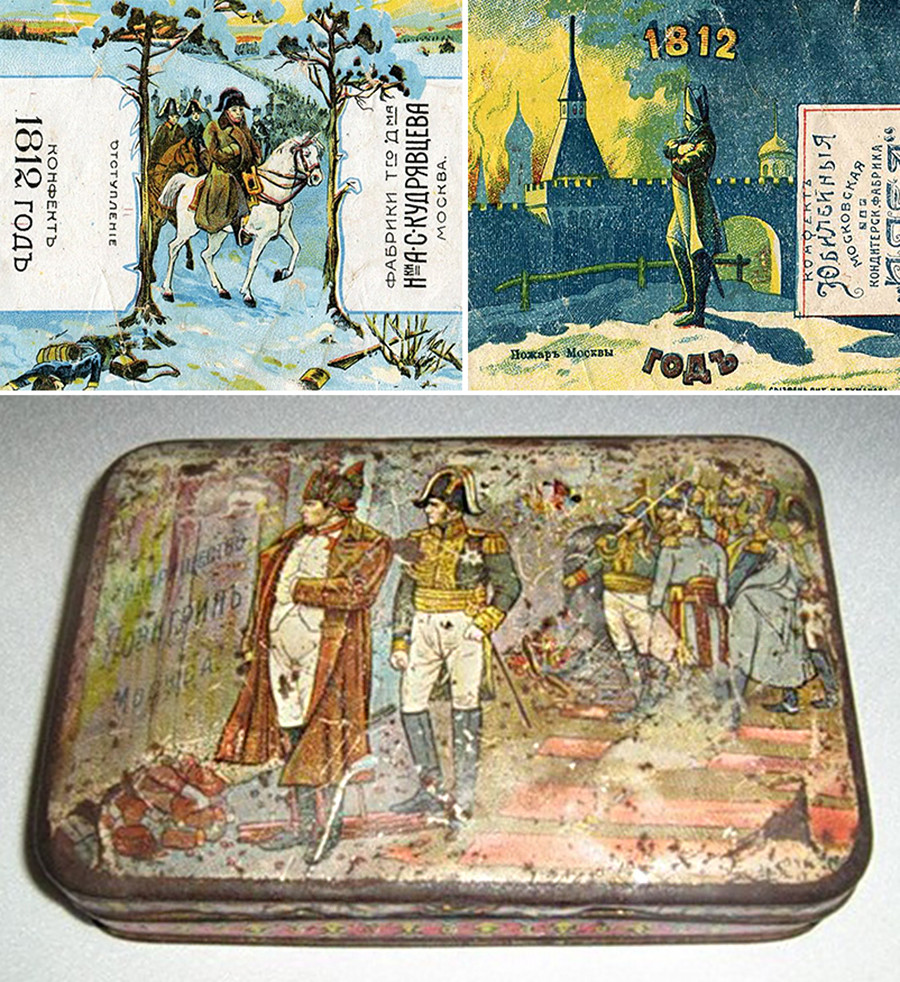

The Einem Company produced a series of 12 high quality chocolate bars called “1812.” Each wrapper had an illustration and text about the military events of that year. For example, “Borodino” chocolate bars contained a text about the legendary Battle of Borodino and the attack of French Marshal Joachim Murat. By collecting all 12 wrappers chocolate lovers not only filled their bellies but also learned about the war in detail.

Some factories even incorporated games with military themes into candy boxed. There was a checkerboard game called “Napoleon’s Banishment from Russia,” which is still played to this day. The goal of the game is to block Napoleon before he crosses the Russian border.

The French military leader’s image was used with great success by candy, tea, and cookie producers on tin boxes – this was where the imagination was let loose. These boxes were decorated not only with Napoleon but other iconic characters from the period. The best Russian artists of the period created the images: Ivan Bilibin, Alexandre Benois, and Mikhail Vrubel, although they didn’t sign off their work so the public was none the wiser.

Meanwhile, a new pastry appeared in the form of Napoleon’s hat, which was layered with cream and cut into triangles. Eventually the pastry became a rectangle, but the name “Napoleon” remained, just as with the cake made with a similar recipe popular in Moscow today.

Napoleon’s image was ubiquitous during that period: It was found on plates, mugs, vases, and even as figures painted onto the bottom of chamber pots - so Russians had something to aim at when nature called!

A taste of ‘Napoleon’

“Bitter Napoleon Tear-Dropper” vodka - Napoleonovsky liqueur and table wine bearing the image of the Eiffel Tower - was also made. Bottles were produced in the form of Napoleon busts with souvenir corks in the form of French imperial eagles.

In an article about the commercialization of the memory of the War of 1812, Vladmir V. Lapin wrote that wine producer Dmitri Travnikov sold Champagne, Napoleonovsky liquor, and Anniversary Brandies.

Moscow’s V. Zimulin Company produced the Anniversary Cognac in bottles with labels showing the seven events of 1812. In order to collect the whole series you needed to buy almost four liters of the drink.

Obviously, not many people today have the same reverence for Napoleon, neither the man nor the brand. But the cake bearing his name remains one of the most popular desserts in modern Russia.

Read our 10 reasons to forget about the calories for a few minutes - 10 mouthwatering Russian cakes you need to try.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox