Ural emeralds, Yakut diamonds and numerous other precious stones are valued all over the world. Both areas are also famous for the mining of gemstones - less valuable, but just as beautiful and revered.

Yakut diamonds near the Mirny mine, 2017.

Alexander Ryumin/TASSYakut diamonds are famous the world over today, although, until the mid-20th century, the stone was only mined in India, Brazil and Africa. Russian geologists had known for a long time that Russia’s coldest region was home to diamond mines, with finds being documented back in the 19th century. Digging, however, didn’t start until the 1930s. Finally, in 1954, the first kimberlite pipe was opened in Yakutia. Others soon followed (By the way, the discovery of diamond mines is being credited to women - Soviet geologists Larisa Popugayeva and Nataliya Sarsadskikh).

Yakut diamonds, Mirny.

Alexander Ryumin/TASSAt different times, diamonds were discovered in the Perm (the Ural Mountains) and Arkhangelsk regions (the Russian North), however, industrial mining is still done in Yakutia. There’s also the concept of the “Russian cut”, which appeared in the 1970s, due to strict Soviet processing standards. It applies not only to Russian-made stones, but all stones with the highest quality cuts are used. They are on average about ten percent more expensive than the rest.

Urals emeralds.

Donat Sorokin/TASSThe only emerald mine in Russia is actually the largest in all of Europe - the Mariinsky Mine (also sometimes known as the Malyshev Mine, as it was called in Soviet times) is located in Sverdlovsk Region in the Ural. Mining started in the 1830s, with large-scale work beginning in the 1920s. Aside from emeralds, geologists were also interested in beryls - not for the purposes of making jewelry, however, but for extracting beryllium oxide, used in military technologies. Today, the Ural yields some 150 kilograms of emeralds annually, all of them of top quality and with a distinct yellow shade. Some of them are humongous in size, such as the one discovered in 2019, weighing a staggering 1.6 kg, and another one in the previous year, coming in at 1.54 kg.

Aside from emeralds and berylls, the Mariinsky Mine yields about five kilograms of alexandrite a year. The stone was discovered during the search for gemstones in the Ural and, initially, geologists mistook it for a low-quality emerald. However, after studying it closer, they realized that it was a completely new, hitherto unknown precious stone.

Alexandrite from the Mariinsky Mine.

Yegor Aleyev/TASSThe find sparkles like an emerald, but changes its color according to lighting conditions - imagine that! Its shades sometimes include green, red and violet. It was named after Russian emperor Alexander II in 1834 and quickly became popular with the Royals and noble elites. Aside from the Ural, the stone is also found in Tanzania and Madagascar.

This is an incredibly beautiful, semi-transparent stone, famous in Russia at least since the 16th century, when it used to be imported from Bohemia (now the Czech Republic). In the mid-19th century, several types of garnet (including the extremely rare green ones) were discovered in the Urals, on the shores of Lake Ladoga and the Kola Peninsula.

Today, garnet is mined in Eastern and Southern Siberia, as well as Karelia. It is one of the most popular and, at the same time, least expensive stones used in jewelry.

Siberian amethysts.

Ilya Naimushin/SputnikAmethysts exhibiting a dark-violet shade are referred to as “Deep Siberian” (sometimes “Deep Russian”) and are considered rare semi-precious stones, which earns them a spot in jewelry making. They are found in the Urals, Siberia and Karelia. Pink amethysts are referred to as ‘Rose de France’ and are encountered more often in nature.

This necklace with amethyst belonged to the popular Russian folk singer Ludmila Zykina.

Gavriil Grigorov/TASSThe Kola peninsula is known for one of the oldest natural sources of the stone in the world, discovered in the 16th century - Cape Korabl (about 300 km from Murmansk), where this silicate can be found right in the cracks of the rocky shores of the White Sea. Beautiful, isn’t it?

The rock with amethysts.

Ivtorov (CC BY-SA 4.0)

Great Imperial Crown of Russia with spinel.

Stanislav Krasilnikov/TASSBack in the days of old, Slavs used to refer to precious red stones as lal, which means “red”. This included rubies and corundums, as well. However, more often than not, spinel was implied. This stone remains on the imperial regalia of the Romanov Dynasty: it adorns the crown of the Russian Empire, silver earrings and the bow clasp; although the particular stones are of foreign origin and, until the 18th century, spinel was considered virtually indistinguishable from rubies.

Catherine the Great's diamond esclavage bow and girandole earrings.

Pavlov/SputnikIn Soviet times, spinel mines were discovered in Yakutia, the Urals and around Baikal. It should be noted that they’re often found in close proximity to precious rubies and sapphires. Spinels are currently not industrially mined in Russia.

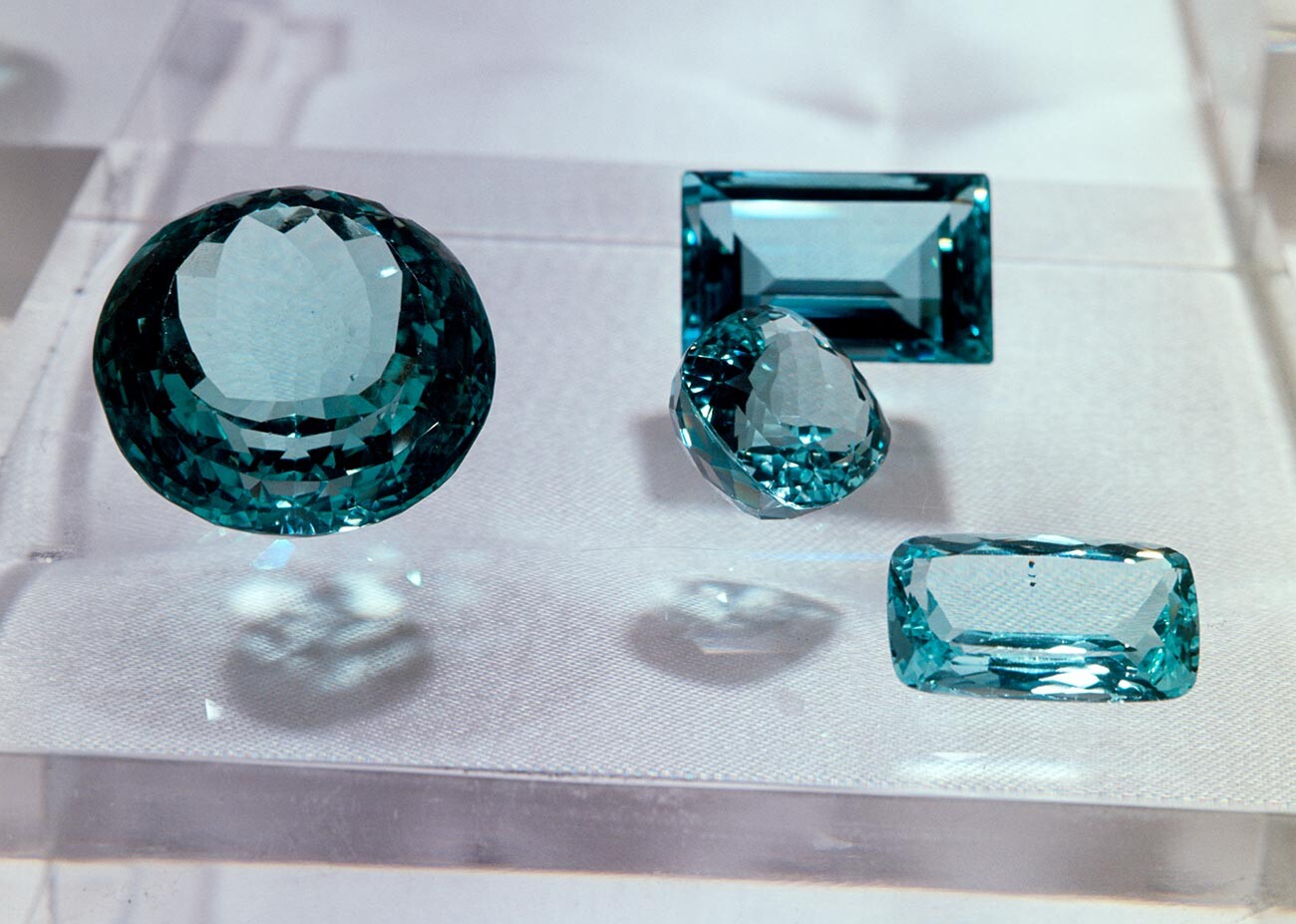

Urals topazes.

SputnikSemi-precious Ural topazes come in many shades - including sky-blue, smokey and all shades of yellow and orange. They’re frequently found in the Ilmen nature reserve in the southern part of the region. Real heavyweights are often found, some weighing up to 30 kg. Russian topazes were always popular jewelry stones both inside and outside Russia, having been popular since the early 19th century.

Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox