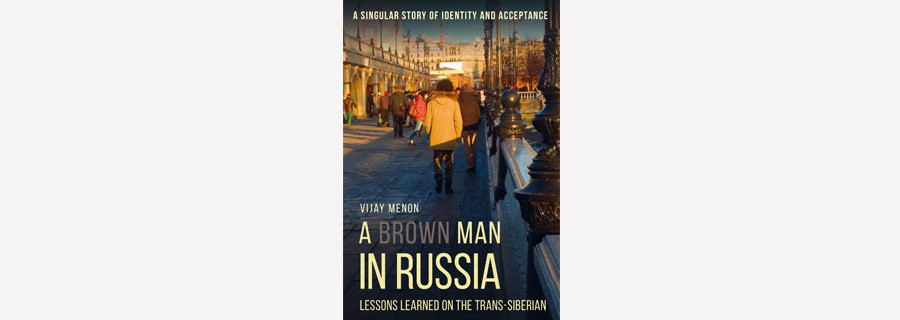

A brown man in Russia: Lessons learned on a Trans-Siberian rail journey

How would you react when meeting absolutely drunk men in army fatigues who invite you to join their party? What if you can’t speak Russian and need to find a flat for the night? How would you explain to a train conductor that you need a ticket to Siberia?

Vijay Menon made a courageous night train journey across

Chapter 11: Do the right thing

December 17-18, 2013

Trans-Siberian Railway → Tyumen,

Book cover

Glagoslav PublicationsThe further away from St. Petersburg, the more barren the horizon became.

Russia is one of the most sparsely populated countries on the planet, with fewer than ten people per square kilometer. Bangladesh, by contrast, packs over 1,000 people per square kilometer, making it greater than 100 times more crowded. In reality, Russia is even less densely populated than the numbers seem, heavily skewed upwards by the urban metropolises of Moscow and St. Petersburg.

When the Chelyabinsk meteor hit in 2013, it killed no one despite packing a punch thirty-three times more powerful than that of the U.S. atomic bomb that decimated Hiroshima. In fact, approximately 100 years earlier, an even bigger meteor exploded near the Tunguska River in Siberia. It was the largest impact event in modern recorded history — and still, not a single soul perished.

The world got lucky when those meteors chose Russia. If the same projectiles had hit Tokyo, for example, millions might have been lost.

And yet even this description does not do justice to the sheer desolation that is Russia. One can

Nonetheless, here we were — sharing a train with hundreds of Russians chugging eastward towards their homes, curious as to the story behind these young Americans who appeared out of place.

I walked up and down the corridor, chary at first of drawing too much attention to myself. In Moscow and St. Petersburg, I was certainly unique — but by no means one of a kind. But the more we moved east, the more my skin tone made me a bonafide celebrity — albeit, perhaps not the most popular one.

One of the benefits of ignorance of the local language is a corresponding blissful obliviousness to the content of what those around you think of you. Nevertheless, it was difficult to lay low when our fellow travelers openly gaped and pointed, whispering clandestine thoughts to their neighbors as I strolled by perfunctorily. For the moment though, none had the courage nor the inclination to approach me — an arrangement that suited me just fine.

Exploring the train was a process awash with small, unexpected delights.

For instance, I was fascinated by the bathrooms. The flush mechanism literally opened the bottom of the toilet bowl, exposing it to the underlying ground and depositing one’s excrement directly onto the tracks beneath. The freezing cold was such that holding down the handle for an extended period of time would cause the inside of the train bathroom to fill extensively with snow and sleet from the outside. Like a mischievous child, I often amused myself by turning the bathroom into a winter wonderland for the unassuming passenger waiting outside to be the next in line for the loo.

Moreover, each section of the train contained a different, cutely designed dining area. I enjoyed people-watching, observing strange foods being eaten, and watching passengers descend into extreme states of inebriation over long periods sitting alone at the bar. When you are trapped in one place for so long, you have no choice but to find ways to entertain yourself.

Our first destination on the train was the city of Tyumen, which is located 2,000 miles from our starting point in St. Petersburg and about 1,600 miles east of Moscow. The town was established in 1586 as the first Russian outpost in Siberia, and today contains about half a million

These facts were only revealed to us

Nothing less, nothing more.

It would take two full days to arrive, so we dug in our heels for the journey at hand. I spent hours lounging on the bed above our mysterious Russian compatriot listening to music on my iPod Shuffle, while Avi and Jeremy lay across from me. But as night fell, I had completely drained the device of

“Shit,” I said. “Does anyone have a charger? I forgot to bring mine.”

Jeremy and Avi shook their heads.

No music for the rest of the trip. I was bummed

“Da!” I exclaimed. “Spasibo!”

Yes! Thank you!

And just like that, we became friends with Slava — the first of many subsequent strangers who would show us great kindness and warmth on the trip

Ordinary Russian train

Legion MediaIt soon became rather evident that Slava — an unassuming and diminutive pale man with a soft face and slim frame — had an intellect to match his boundless generosity. A voracious learner, he soon began demanding that we teach him English numbers, mastering the entire set up to one million within the course of an hour. He then asked us many questions, a clear effort to improve his mastery of the language.

Where were we from? What were we up to? And, most importantly — why Tyumen?

We didn’t have a satisfactory answer for that one.

After some banter, Slava pointed to our

“Are you very good?” I asked.

“No. I am a beginner,” he fibbed. “Let’s just play for fun, though.”

Confidently, I seated myself at the board. Fewer than three minutes later, my king had been vanquished.

“You’re a hustler!” I joked.

“Again,” he requested.

Slightly demoralized, but taking solace in the fact that it couldn’t get much worse, I rose up for the challenge once more. On my second move, I played a knight out in front of my pawn — a classic opening for me.

“Take it back,” Slava demanded, a look of disgust etched upon his face.

“What?”

I was perplexed.

“Take it back,” he repeated. “Trust!”

“Let’s just play it out, Slava,” I replied, bemusedly.

Irritated, Slava proceeded to pantomime the following eight hypothetical moves that would proceed my catastrophic turn — demonstrating, beyond a shadow of

“Jesus,” I thought. “Am I playing Slava or Garry Kasparov?”

Vijay Menon

Personal archiveSheepishly, I pulled the piece back. But it was of no use. Resistance, as they say, was futile.

Within ten minutes I again had been defeated— and so too, would Avi and Jeremy subsequently fall. After he had knocked off the three of us, we decided the only recourse was to take him down a notch, and we had just the antidote to do so — alcohol.

We pulled out a couple of 40-ounce bottles of Gold Mine beer — a substance so poor it garnered a three-percent rating on BeerAdvocate.com* — and imbibed with our new friend before passing out for the night.

Smiles were shared and laughs were had. This was why we came to Russia.

* Every frat daddy’s favorite resource, this website ranks beers on a scale of 1 to 100.

Read more: The Platskart Diary: Traveling from Moscow to Vladivostok by train

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox