10 New York City places that have hidden Russian history

“New York City is where Russia and the Arts - as well as Russia and Politics - meet and sometimes collide,” says critically-acclaimed travel and culture writer, Prof. Barry Goldsmith, who is also a long-time resident. Here are 10 places in New York City that are now a part of Russian history and culture.

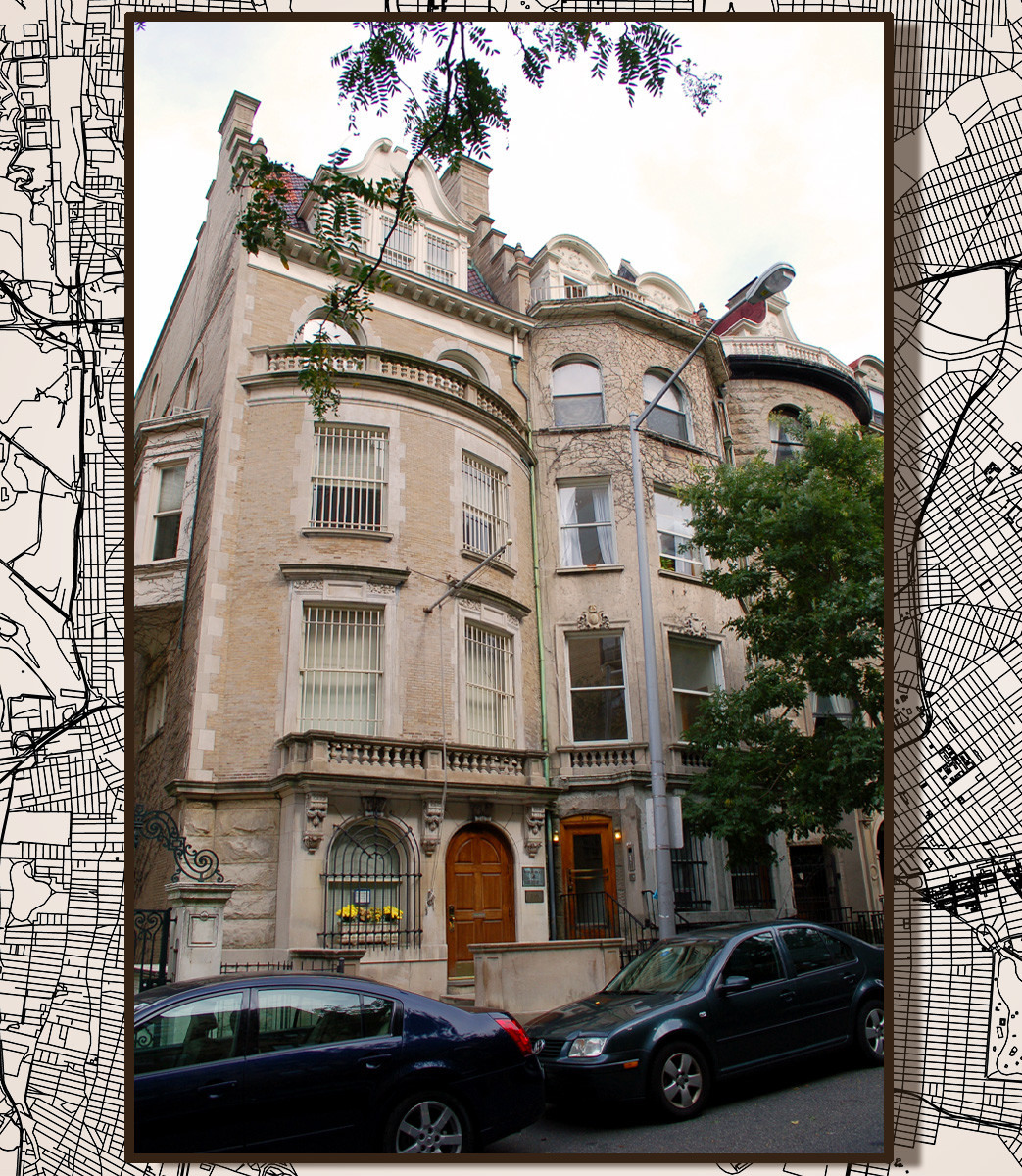

1. Home of former Russian Prime Minister Alexander Kerensky

111 East 91st Street

Kerensky lived the last 20 years of his life here, occupying the entire top floor. (He also taught Russian history and politics at Stanford University in California).

In 1917, socialist revolutionary Kerensky was head of the moderate government that was violently overthrown by Lenin and the Bolsheviks. After escaping from Russia, Kerensky fled to Europe, and after World War II, he settled in New York, dying at St. Luke’s Hospital in 1970.

2. Roerich Museum

319 West 107th Street

This is the world’s second largest and finest collection of art works by the great mystical and modern Russian artist, Nikolai Roerich, who lived in the USA in 1920-23. This private museum was founded in 1923, when Roerich had a huge following in America, thanks to the popularity of his philosophical teachings of global peace and harmony.

Today, this three-story Upper West Side townhouse has nearly 200 of his artworks, ranging from paintings of the Himalayas to sketches of stage sets for Russian ballets. The museum still promotes Roerich’s ideas about global harmony, which is visually conceptualized in his philosophical symbol and the motto, Pax Cultura (Peace Through Culture).

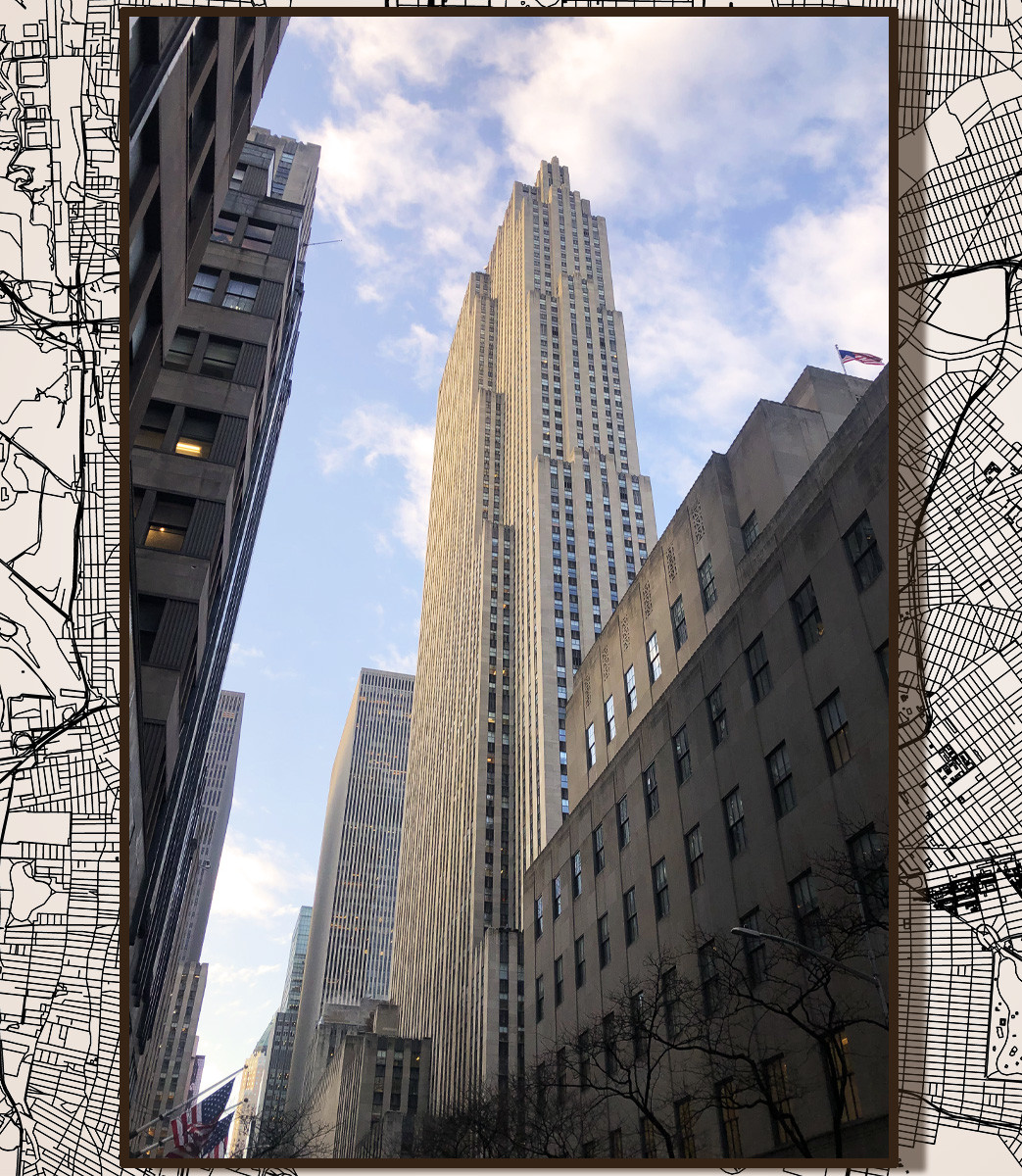

3. RCA Building

30 Rockefeller Plaza

Thanks to their collaboration, David Sarnoff and Vladimir Zworykin developed the first television set, which was produced by the Radio Corporation of America (RCA). Sarnoff, who was born in Minsk (then part of the Russian Empire), was the company’s CEO, while Zworykin, who was born in Murom but studied in St. Petersburg, was the genius inventor.

This 1930s Art Deco skyscraper is the centerpiece of the famous Rockefeller Center. The Standard Oil Company, which was America’s most powerful company, controlled by oligarch John D. Rockefeller, decided to move its main office to the RCA Building, which was slated to open on May 1, 1933. Vladimir Lenin, however, even though long dead, managed to delay the opening for two weeks, because of a controversy over ‘Man at the Crossroads’, a painting by left-wing artist Diego Rivera. “It was in Sarnoff's RCA building that America’s most renowned capitalist - Rockefeller - commissioned murals from communist Diego Rivera,” says Prof. Goldsmith. “The result was an artistic collision between Capitalism and Communism, when Rivera included a portrait of Lenin with portraits of the Rockefellers. Capitalism won when Rockefeller ordered all the murals destroyed.”

4. Lower East Side

This entire district was the first home in New York City for more than 1 million Jewish immigrants from the Russian Empire. The Lower East Side (LES) became one of the world’s most densely populated neighborhoods at the time.

Abraham Cahan, editor at the Forward, the most popular Jewish newspaper, wrote that the neighborhood “covers a comparatively small area, something less than half a square mile, wherein is crowded a little city of its own with a population of 500,000 souls: men, women, and children, almost exclusively Polish and Russian Hebrews.”

There were dozens of synagogues, Yiddish theaters and Yiddish newspapers. Out of the Shadow: A Russian Jewish Girlhood on the Lower East Side is Rose Cohen's eyewitness account of the harsh reality of tenement life and sweatshops.

5. Russky Samovar

256 West 52nd Street

In the late Soviet era, this popular restaurant was a meeting place for important émigré intellectuals and creative minds. Russky Samovar started in 1986 when Soviet émigrés Roman Kaplan, ballet master Mikhail Baryshnikov and Nobel laureate poet Joseph Brodsky decided to open a restaurant where Frank Sinatra once had a hang-out in Midtown Manhattan. Brodsky’s favorite table is still there, as is Baryshnikov's baby grand piano, which is still in use. The restaurant is also famous as the place of a romantic scene between Baryshnikov and Sarah Jessica Parker in the U.S. TV show ‘Sex and the City’.

6. Lev Theremin apartment. 37 West 54th Street

According to many, Russian inventor Lev Theremin was the founder of electronic music. In 1918, using newly discovered vacuum-tube technology, he designed and built the first musical instrument that relied on electronic oscillation to produce sound. In 1927, he came to New York, where he also created the world’s first electronic security system, which he installed at New York’s Sing Sing Prison. Luminaries such as Albert Einstein played the violin at recitals held at Theremin’s apartment. The inventor was a celebrity in New York in the late 1920s and 1930s, but in 1938, he was kidnapped by Soviet agents and returned home.

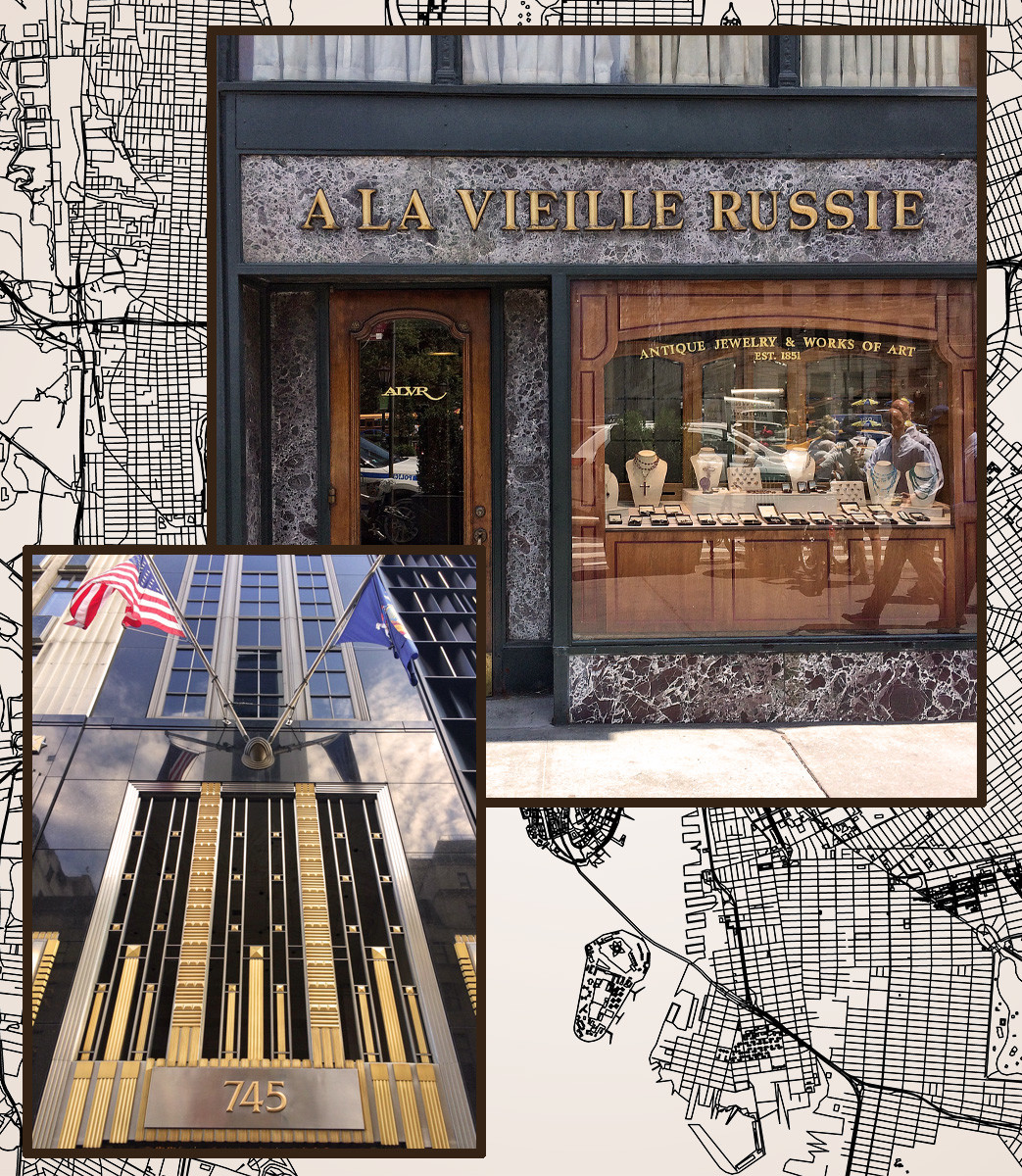

7. A La Vieille Russie jewelry store

745 Fifth Avenue

Above: The historical building is 781 Fifth Avenue. Below: The new location on 745 Fifth Avenue.

A La Vieille RussieFounded in Kiev (the Russian Empire) in the mid-1800s, this upscale store has been an icon of New York City high society since 1930, selling Faberge and other exquisite Russian jewelry. Throughout the 20th century the elite of New York City and from all over the world were regular buyers of Russian treasures at A La Vieille Russie.

“My grandparents introduced Fabergé’s beautiful works of art to the United States, and A La Vieille Russie is proud to have been offering exquisite and exclusive antique jewelry and Russian Imperial treasures in New York City continuously since the 1920s,” said Mark Schaffer, a member of the family that owns the store.

8. General Post Office

8th Avenue and 40th Street

Built in 1912, the vestibule of New York City's main post office displays the official emblems of the leading nations that founded the Universal Postal Union. Therefore, it’s little surprise that a huge copy of the Russian imperial eagle is on the ceiling. Nevertheless, today many native New Yorkers are in shock when they see it for the first time.

9. Carnegie Hall

881 7th Avenue

On May 5, 1891, Pyotr Tchaikovsky conducted the New York Symphony orchestra during Carnegie Hall's grand opening. The board of directors had implored the great Russian conductor to make the nine-day journey across the Atlantic Ocean. At this time, St. Petersburg was a global capital of culture, while New York was still a cultural backwater, though a city with many new wealthy families with grand ambitions. Tchaikovsky conducted his own musical works in several concerts at Carnegie Hall as part of the opening week.

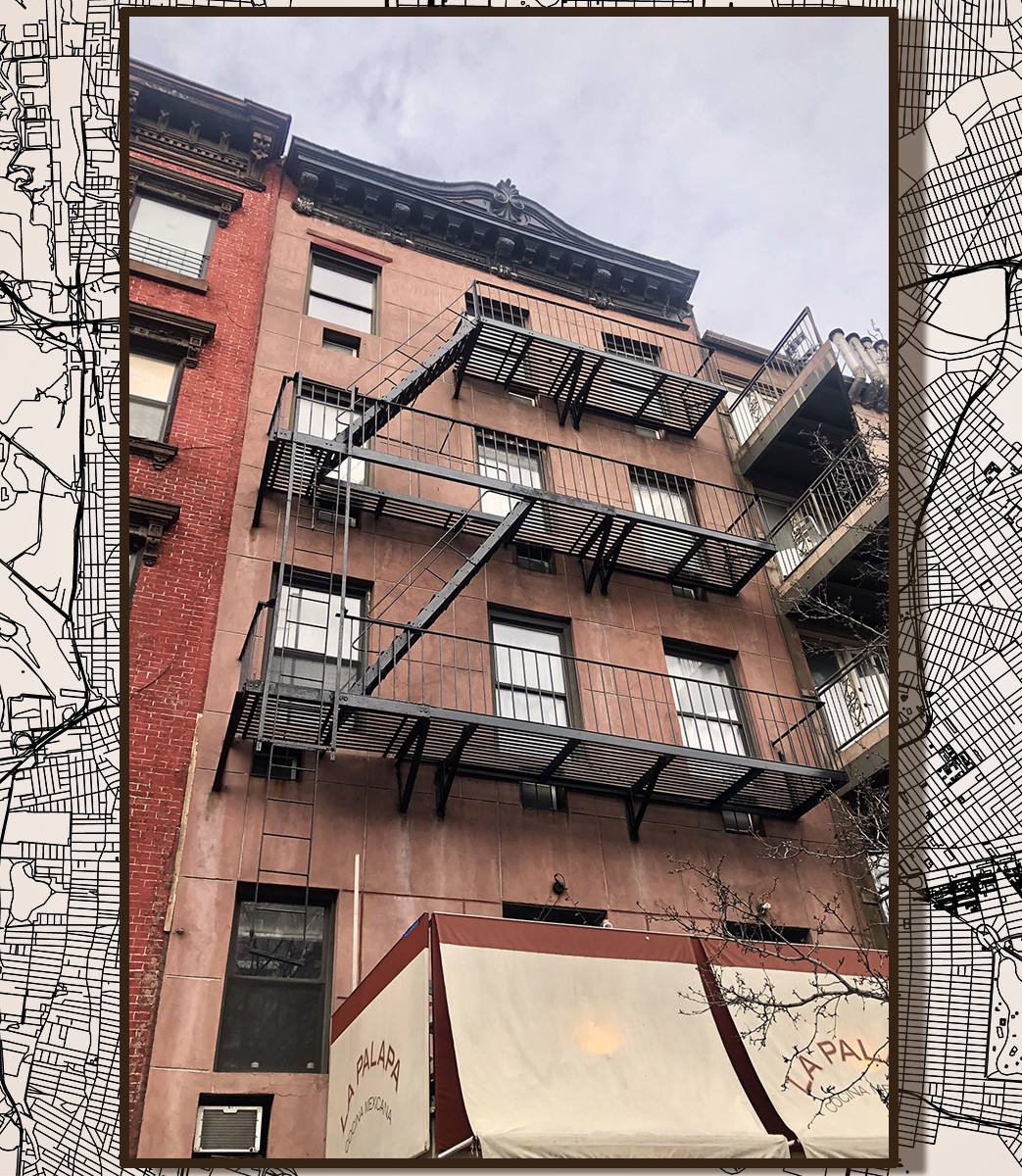

10. Trotsky and Novy Mir headquarters

77 St. Mark's Place (East Village)

This address was the headquarters of Novy Mir, a small Russian revolutionary newspaper in exile, edited by Nikolai Bukharin and Alexandra Kollontai.

On January 14, 1917, America welcomed a very unusual refugee from Europe - the infamous revolutionary, Leon Bronstein (Trotsky). When he sailed into New York harbor his name was already so well known that major newspapers, such as the New York Times, wrote about his arrival. Trotsky lived in the Bronx near Crotona Park, and almost every day he rode the subway to go to work at Novy Mir; meanwhile, his sons went to public school in the Bronx.

Trotsky gave over 30 revolutionary speeches at places such as Cooper Union and Beethoven Hall. When Tsar Nicholas II abdicated on March 15, Trotsky returned to Petrograd. After the Bolshevik seizure of power in November he took a key position in the new Soviet government, helping to create and lead the Red Army. This prompted the Bronx Home News to run a headline: “Bronx Man Leads Russian Revolution.”

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox