Rival to Moscow’s Kremlin: Exploring the Savior Monastery in Suzdal

Suzdal. Savior-St. Evfimy Monastery, west view across Kamenka River. Left center: cupolas of Transfiguration Cathedral, Church of the Intercession. May 29, 2009

William BrumfieldAt the beginning of the 20th century Russian chemist and photographer Sergei Prokudin-Gorsky developed a complex process for vivid, detailed color photography. Inspired to use this new method to record the diversity of the Russian Empire, he photographed numerous historic sites during the decade before the abdication of Tsar Nicholas II in 1917.

Suzdal. View north from bell tower of Convent of the Deposition of the Robe. Distant left: Savior-St. Evfimy Monastery with Intercession Church (left), Transfiguration Cathedral, Gate Church of Annunciation. Summer 1912

Sergey Prokudin-GorskyHis vision of photography as a form of education and enlightenment was demonstrated with special clarity through his photographs of medieval architecture in historic settlements northeast of Moscow, such as Suzdal, Vladimir and Pereslavl-Zalessky.

The Suzdal’ Connection

In the summer of 1912, Prokudin-Gorsky visited the ancient town of Suzdal’, a center of medieval Russian heritage. Bypassed by railroad construction and with little industry, Suzdal managed to retain a bucolic atmosphere captured so poignantly in Prokudin-Gorsky’s photographs.

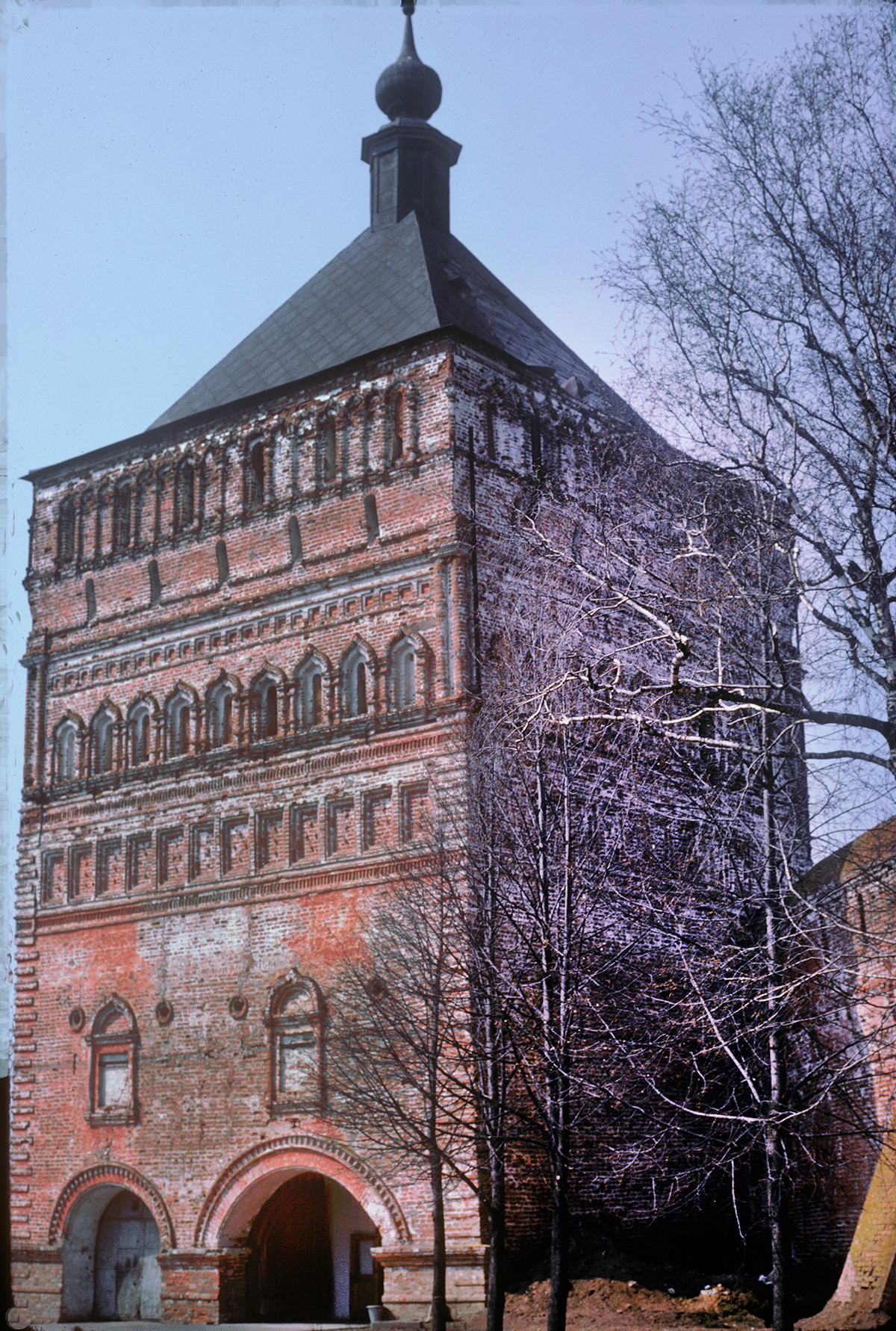

Savior-St. Evfimy Monastery, west wall & towers. Summer 1912

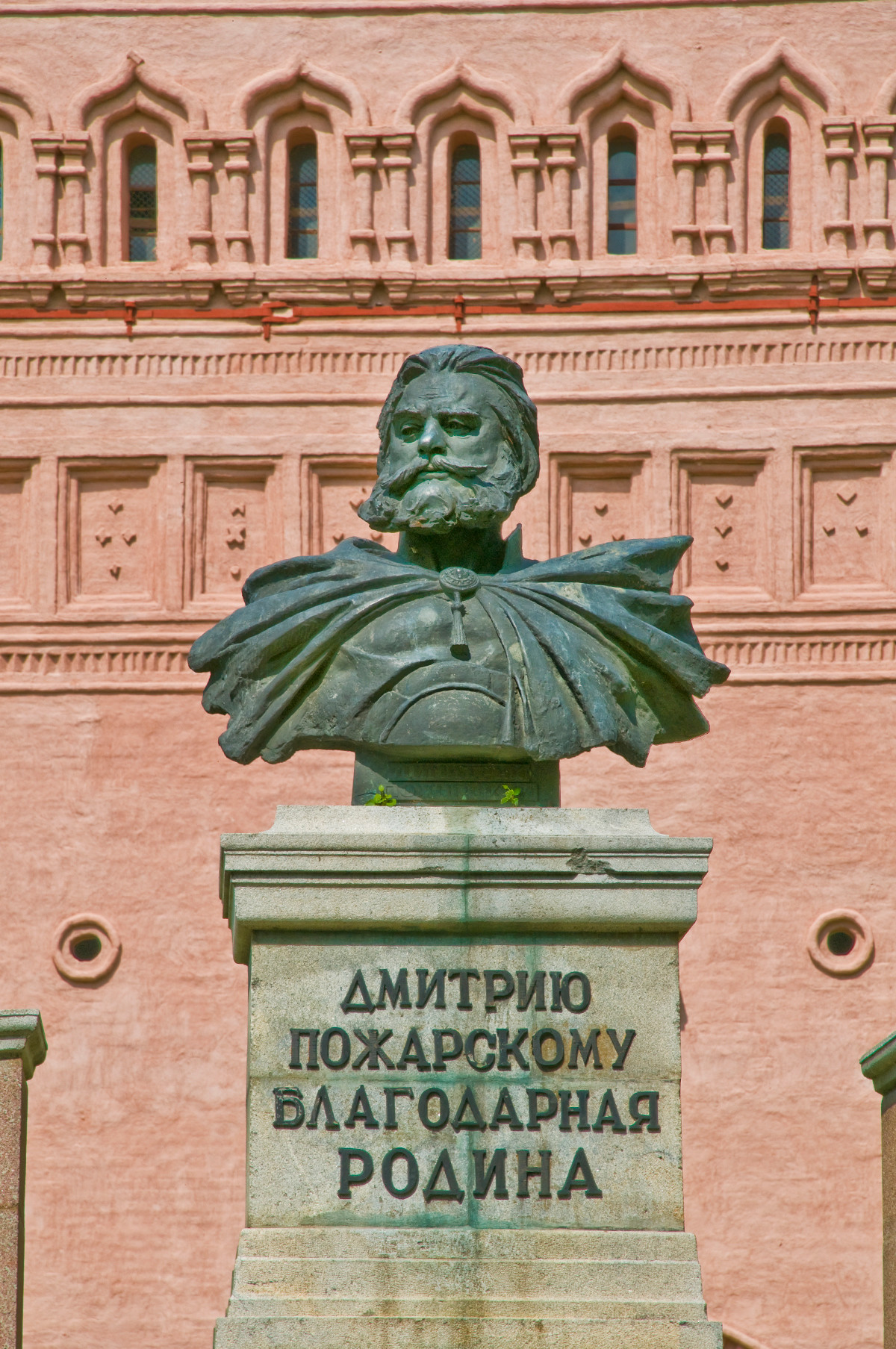

Sergey Prokudin-GorskyAt the time of his visit, the town had about 7,000 inhabitants (the current population is 10,000) with an extraordinary concentration of churches and monasteries. Suzdal was also renowned for its connection with the family of Prince Dmitry Pozharsky, a national hero during the Time of Troubles in the early 17th century.

The first mention of Suzdal occurred in the year 1024, yet there were undoubtedly settlements of Finno-Ugric and Slavic peoples in the area by the 9th and 10th centuries. By the early 11th century, Kiev - the political center of ancient Rus’ - had extended its political and religious authority into this fertile agricultural territory.

Savior-St. Evfimy Monastery, west wall & towers. March 5, 1972

William BrumfieldAt the turn of the 12th century, Prince Vladimir Monomakh of Kiev arrived with a new wave of settlers. Monomakh erected a citadel (kremlin) above the small Kamenka River and, around 1102, began construction of the Suzdal cathedral.

Suzdal’s decades-long reign

Savior-St. Evfimy Monastery, south wall & main entrance tower. From contact print album (original 3-color glass negative missing). Summer 1912

Sergey Prokudin-GorskyOver decades as the center of a powerful principality, Suzdal gained several monasteries, of which the largest and perhaps wealthiest was dedicated to the Transfiguration of the Savior, one of the most august of Orthodox holidays. During his productive activity in Suzdal, Prokudin-Gorsky took five views of this monastery. My work there spans several decades, from 1972 to 2009. Much has changed over that interval, including the painted facades of several structures.

Savior-St. Evfimy Monastery, main entrance tower. April 27, 1980

William BrumfieldThe monastery was founded in 1352, during the reign of Prince Boris Konstantinovich, who used its location on a high bluff over the Kamenka River to create a monastic fortress (In medieval Russia, monasteries frequently doubled as fortifications). This position is clearly visible in Prokudin-Gorsky’s stunning panoramic view taken from the bell tower of the Convent of the Deposition of the Robe.

The Great Walled Citadel

The founder and first abbot was monk Evfimy (Euthymius), canonized during the Makaryev Church Councils convened by Metropolitan Macarius of Moscow in 1547-49 to recognize Russian spiritual leaders. The monastery was subsequently renamed Savior-St. Evfimy (Spaso-Evfimiev) in his honor.

The monastery’s great walled citadel, completed with twelve towers in 1664, is the subject of two detailed views by Prokudin-Gorsky. Possessor of over 10,000 serfs, the monastery had the resources for such an enormous project, comparable in some ways to the Moscow Kremlin. (The monastery walls are 1,200 meters in length, while the Moscow Kremlin walls are 2,350 meters long with twenty towers.)

Monument to Prince Dmitry Pozharsky. Background: Main entrance tower of Savior-St. Evfimy Monastery. May 29, 2009

William BrumfieldAs the burial place of Prince Dmitry Pozharsky (1577-1642), the monastery had the character of a secular shrine and was used for state purposes at the turn of the 18th century. The main tower, square in plan and 22 meters in height, provided an imposing entrance not only with its massive bulk but also with its decorative friezes, including a row of “gothic” ogival window surrounds.

Then and Now: a comparison

In Prokudin-Gorsky’s two photographs and in mine from the 1970-90s, the brick surface of the walls is clearly visible. My 2009 photographs show the walls covered with a protective coating that concealed the white mortar seams.

Savior-St. Evfimy Monastery. Church of the Intercession with attached refectory. Southeast view. April 27, 1980

William BrumfieldThe monastery’s most distinctive monument is the Church of the Dormition, with an attached refectory (dining hall). Formerly dated as from 1525, the Dormition Church now appears to have been constructed no earlier than in the last quarter of the 16th century. Distantly visible in Prokudin-Gorsky’s panorama, its “tent” tower resembles the central tower of St. Basil’s in Moscow (1555-61) and may well have been influenced by it.

The monastery's main church, the Cathedral of the Transfiguration of the Savior (1582-94), is also visible in Prokudin-Gorsky panoramic view. Its form is typical of monastery cathedrals of the middle of the 16th century, which were themselves imitations of Aristotle Fioravanti's Dormition Cathedral, erected in the Moscow Kremlin in the 1470s. The blind arcading on the Transfiguration Cathedral facades reflects both 15th-century Muscovite and 13th-century Suzdalian motifs.

Savior-St. Evfimy Monastery. Cathedral of the Transfiguration of the Savior, south facade with remnants of frescoes (subsequently whitewashed). Right foreground: early 16th-century Chapel of St. Evfimy. March 5, 1972

William BrumfieldAt the cathedral’s southeast corner is the graceful Chapel of St. Evfimy, built in 1507-11 over the grave of Evfimy and thus the monastery’s oldest surviving structure. Originally dedicated to the Transfiguration, the shrine was rededicated in honor of Evfimy after the completion of the larger Transfiguration Cathedral in 1594.

Withstanding the Test of Time

The cathedral took its present shape at the end of the 16th century, although it was subsequently modified many times. The frescoes that cover the interior were painted in 1689 by a group of masters from Kostroma. My 1972 view also shows exterior frescoes, subsequently whitewashed.

Savior-St. Evfimy Monastery. Church of the Nativity of John the Baptist, with attached belfry. Northwest view. Far right: corner of Intercession Church. Summer 1912

Sergey Prokudin-GorskyProkudin-Gorsky paid more attention to a small three-tiered tower church dedicated to the Nativity of John the Baptist and tentatively dated as from the early part of the 16th century. The structure was subsequently modified with the construction and enlargement of an adjoining belfry in 1599 and again in 1691.

Although the original glass color negative has not been preserved, the structure was painted dark red when Prokudin-Gorsky photographed it. In my 1995 view, the entire edifice was whitewashed. Now the belfry is once again red, thus demonstrating that Russia’s brick churches were often repainted in various colors.

Savior-St. Evfimy Monastery. Church of the Nativity of John the Baptist with attached belfry. Northwest view. June 30, 1995

William BrumfieldProkudin-Gorsky also photographed the delightful, if somewhat primitive,s Church of the Annunciation over the Holy Gate, erected at the turn of the 17th century. It, too, has changed colors over the decades. The south facade, visible in both our photographs, has the playful appearance of a human face, with the gateway for a mouth.

The Prison Monastery

Like other monastic retreats in Suzdal, the Savior-St. Evfimy Monastery has its macabre secrets. In the 1760s, Catherine the Great decreed that part of the monastery serve as a place of incarceration for “deranged criminals”, whose crimes usually involved public expression of negative opinions about the autocratic regime and the church. Records show that several of these unfortunates, many of them Old Believer Orthodox Christians, were held for many years in isolation cells.

Savior-St. Evfimy Monastery. Church of the Annunciation over Holy Gate, south view. Summer 1912

Sergey Prokudin-GorskyThe monastery was visited in 1837 by future Tsar Alexander II and again, in 1913, by Nicholas II and his four daughters. After being closed in the early 1920s, the monastery was converted into a state prison of high importance. During the 1920s and 30s, its walls incarcerated Orthodox Church prelates, as well as notable Communist officials.

Perhaps its most notorious “guests” were German and other Axis high officers captured as a result of the Red Army’s triumph at Stalingrad in early 1943. They included field marshal Friedrich Paulus, who famously surrendered despite Adolf Hitler’s expectation that he would commit suicide.

Savior-St. Evfimy Monastery. Church of the Annunciation over Holy Gate, south view. March 5, 1972

William BrumfieldAfter the war, the monastery served until the 1960s as a place of detention for juvenile delinquents. With the designation of Suzdal as a major tourist development in the mid-1960s, the Savior-St. Evfimy Monastery ensemble was transferred to the Vladimir-Suzdal Museum Preserve, founded in 1958 and now one of the largest such institutions in Russia. With the monastery’s preservation, Prokudin-Gorsky’s photographs have become a priceless record of this great ensemble before the cataclysms of the 20th century.

In the early 20th century, Russian photographer Sergei Prokudin-Gorsky devised a complex process for color photography. Between 1903 and 1916 he traveled through the Russian Empire and took over 2,000 photographs with the process, which involved three exposures on a glass plate. In August 1918, he left Russia and ultimately resettled in France with a large part of his collection of glass negatives. After his death in Paris in September 1944, his heirs sold the collection to the Library of Congress. In the early 21st century, the Library digitized the Prokudin-Gorsky Collection and made it freely available to the global public. A few Russian websites now have versions of the collection. In 1986, the architectural historian and photographer William Brumfield organized the first exhibit of Prokudin-Gorsky photographs at the Library of Congress. Over a period of work in Russia beginning in 1970, Brumfield has photographed most of the sites visited by Prokudin-Gorsky. This series of articles juxtaposes Prokudin-Gorsky’s views of architectural monuments with photographs taken by Brumfield decades later.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox