The many lives of Kostroma’s Epiphany-St. Anastasia Convent

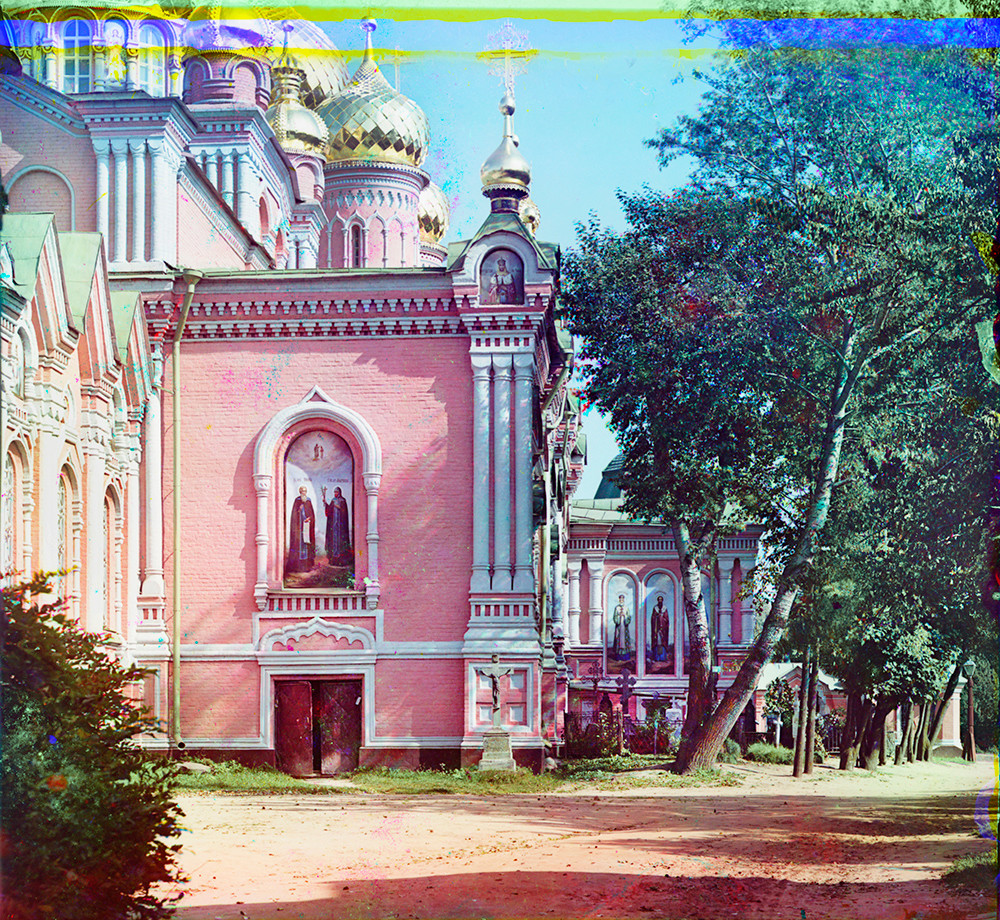

Kostroma. Epiphany-St. Anastasia Convent. From left: Church of Smolensk Icon of the Virgin, Epiphany Cathedral, Tretyakov Building. August 12, 2017.

William BrumfieldOf the many historic towns along the Volga, Kostroma rivals its neighbor Yaroslavl for the beauty of its churches and for the important role it has played in Russian history. It was a favorite spot of Russian photographer and chemist Sergei Prokudin-Gorsky, who made two trips to Kostroma, in 1910 and 1911. Among the historic monuments that he photographed was the Epiphany-St. Anastasia Convent, whose turbulent history reflects that of Kostroma itself over a period of several centuries.

Epiphany-St. Anastasia Convent. West wall & gate tower. August 12, 2017.

William BrumfieldAlthough historical evidence is sparse, it is commonly thought that Kostroma was founded in the early 1150s by Yury Dolgoruky, ruler of the dominant Vladimir principality and known as the founder of Moscow (1147). The earliest documented reference to Kostroma dates to 1213, when the settlement – built entirely of wood – as burned by Prince Konstantin during a territorial feud with his brother Yury. In the second half of the 13th century, the Kostroma principality became an important political center, but by 1364 it had been absorbed into the expanding Muscovite state.

Religious center

The Kostroma area was known for its monastic institutions, such as the Ipatiev Monastery, one of the most important in Russia. The Epiphany Monastery was established in 1425 by the monk Nikita, a pupil of St. Sergius of Radonezh, the avatar of Muscovite monasticism. Nikita had earlier been abbot of the prominent Vysotsky Monastery in the town of Serpukhov.

Epiphany-St. Anastasia Convent. Epiphany Cathedral, southeast view with original 16th-century structure & gallery (left) added in late 1860s. August 12, 2017.

William BrumfieldIn the middle of the 16th century during the reign of Ivan the Terrible, work began on the monastery’s first masonry structure, the Epiphany Cathedral, located on the site of the original wooden church. A major supporter of the construction was Prince Vladimir Andreyevich Staritsky (1533-69), grandson of Grand Prince Ivan III of Moscow and cousin of Ivan the Terrible.

Kostroma. From left: Church of Nativity (razed); West gate tower of convent; fire watch tower with convent Church of Smolensk Icon behind; convent Epiphany Cathedral; Church of St. Nicholas (razed); I. P. Tretyakov building. Summer 1910.

Sergey Prokudin-GorskyThe structure had five domes, and like many other large cathedrals of the 16th century, its design was based on the form of the Dormition Cathedral in the Moscow Kremlin. Completed in 1565 and considered the oldest surviving monument in Kostroma, the Epiphany Cathedral soon witnessed dramatic events leading to a murderous conclusion – a sequence characteristic of Ivan’s reign.

A challenging history

In 1569, Vladimir Staritsky was appointed the commander of a Russian force sent to defend the fortress of Astrakhan, which had been conquered by Ivan in 1556. Staritsky’s route down the Volga passed through Kostroma, where he was greeted enthusiastically and given hospitality by Abbot Isaiah at the Epiphany Monastery.

Epiphany-St. Anastasia Convent. Epiphany Cathedral. South gallery & entrance (late 1860s). August 12, 2017.

William BrumfieldDespite the terrible tsar’s apparent favor, Vladimir Staritsky was already under Ivan’s suspicion as a potential dynastic rival. Seized by jealous suspicions on hearing of Startisky’s reception in Kostroma, Ivan was encouraged to act by his close advisors.

Staritsky was arrested in October 1569 at Ivan’s fortified compound of Alexandrov near Moscow and forced to take poison. His wife and older daughter were also killed, as was his mother, Evfrosiniya, who was in exile at the Goritsky Convent on the northern Sheksna River. Staritsky was subsequently buried with honors in Moscow’s Archangel Cathedral, where he rests near his father, Andrey, an earlier victim of Moscow’s dynastic intrigues.

Epiphany Cathedral. Southwest corner with south gallery of "new" cathedral. Summer 1910.

Sergey Prokudin-GorskyIvan’s rage was not sated by his rampage through the Staritsky family, however. In 1570, he also ordered the execution of Isaiah as well as many of the monastic brethren who had greeted Staritsky warmly.

The Epiphany Monastery survived, but was swept by violence again during the early 17th-century dynastic crisis known as the Time of Troubles. Amid a general collapse of state authority, Kostroma was sacked in 1608 by Polish-Lithuanian cavalry leader Aleksander Lisowski, who raided many Russian towns from 1608 to 1615 until his sudden death in 1616. During the 1608 raid, Lisowski’s forces overcame the monastery’s wooden fortifications and massacred those who had taken shelter there.

Epiphany Cathedral, north gallery & "new" cathedral (late 1860s). Left background: original 16th-century cathedral. August 12, 2017.

William BrumfieldWith the election of the young Michael Romanov as tsar in 1613, order gradually returned to the ravaged lands of central Russia. The town benefited from the Romanov family’s ancient connections to Kostroma (and especially to the Ipatiev Monastery) as well as its advantageous location on the Volga.

Restoration and decline

At the Epiphany Monastery, new churches arose, and the monastery walls were rebuilt of brick with six large towers in 1642-48. Exterior galleries were added to the Epiphany Cathedral, and the renowned Kostroma masters Gury Nikitin and Sila Savin painted its interior with frescoes. Unfortunately, these 17th-century frescoes have not survived.

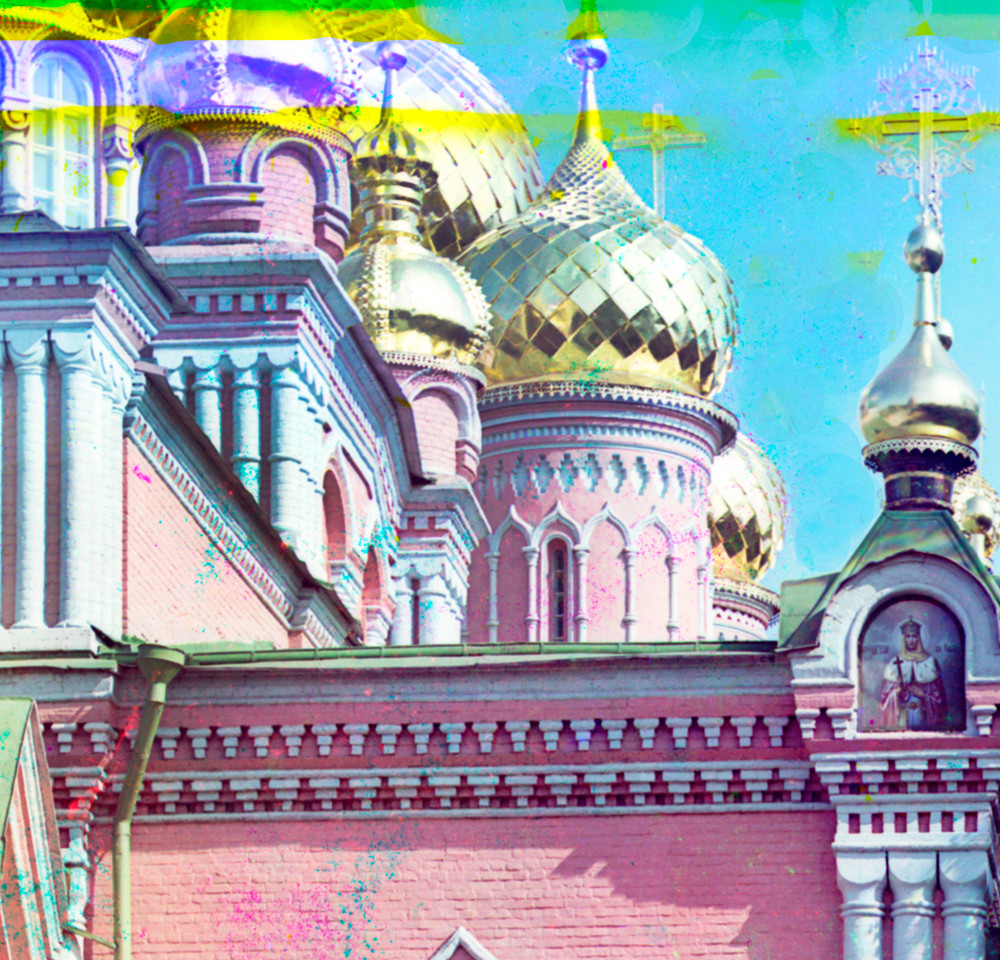

Epiphany Cathedral. Southwest corner detail with golden cupolas of original 16th-century structure. Summer 1910.

Sergey Prokudin-GorskyDespite large donations form the wealthy Saltykov family, the fortunes of the Epiphany Monastery waned, and it suffered from large fires that swept through Kostroma, like so many other provincial towns. The damage from a fire in 1847 was so severe that church authorities decide to close the monastery. Some of its buildings were demolished for their bricks, Tsar Nicholas I ordered that the Epiphany Cathedral be conserved as an architectural landmark.

At this point, the monastery’s fate intersected with that of another ancient monastic institution, the Convent of St. Anastasia, founded presumably around the turn of the 15th century. Some historians suggest that it was established by Princess Anastasia Dimitrievna, daughter of Moscow’s heroic Grand Prince Dimitry Donskoi. In the 16th century the convent was patronized by Tsaritsa Anastasia Romanovna Zakharina-Yureva (1530-60), the widely admired first wife of Ivan the Terrible and great-aunt of Tsar Michael Romanov.

Epiphany Cathedral. South view with golden cupolas of original 16th-century structure. August 12, 2017.

William BrumfieldThe convent of St. Anastasia was burned in Lisowski’s 1608 raid and was revived only to be closed in 1764 during Catherine the Great’s reforms of the church administration. The convent was re-established in 1773, after another Kostroma fire, and then expanded rapidly during the mid-19th century.

In 1863, its mother superior Maria (Davydova) petitioned to be granted the largely abandoned territory of the Epiphany Monastery. With this move, the renamed Epiphany-St. Anastasia Convent underwent a period of repair and reconstruction.

Epiphany Cathedral. Interior of "new" cathedral with recent frescoes. View east toward icon screen. August 12, 2017.

William BrumfieldParticularly affected was the Epiphany Cathedral, which was reshaped in 1864-69 by the addition to the west façade of a large brick structure in the “Russian Revival” style. Consequently, the 16th-century structure became the sanctuary (with the main altar) of the enlarged cathedral. The new structure also contained secondary altars dedicated to St. Anastasia the Roman, St. Nicetas and St. Sergius of Radonezh, thus rendering homage to the combined monasteries’ spiritual heritage.

Prokudin-Gorsky’s one known photograph of the convent shows the southwest corner of the cathedral, with its joining of old and new structures. My photographs, taken from different perspectives in 2017, show whitewashed walls of the new structure instead of the pink facades and paintings of saints within window enclosures seen Prokudin-Gorsky’s view.

Epiphany Cathedral. Interior of "new" cathedral with icon screen. August 12, 2017.

William BrumfieldAfter the closing of the convent in 1918, the Epiphany Cathedral functioned as a parish church until 1925, when it was repurposed as an archive. In 1982, a fire in the archive destroyed remaining fragments of the 17th-century frescoes.

In 1990 the Epiphany-St. Anastasia Convent was revived, and the following year its re-consecrated primary shrine became the main cathedral of the Kostroma Diocese. Shortly thereafter, the cathedral received the eponymous St. Theodore Icon of the Virgin, considered the palladium of Kostroma and especially venerated by the Romanovs. In 2010-13 the Epiphany Cathedral interior was repainted.

Although we have only one photograph of the convent by Prokudin-Gorsky, his view, with its wealth of detail, reconnects strands of history that were severed over a period of unfathomable turbulence.

Epiphany Cathedral. Northeast view of original 16th-century structure. August 12, 2017.

William BrumfieldIn the early 20th century the Russian photographer Sergei Prokudin-Gorsky devised a complex process for color photography. Between 1903 and 1916 he traveled through the Russian Empire and took over 2,000 photographs with the process, which involved three exposures on a glass plate. In August 1918, he left Russia and ultimately resettled in France with a large part of his collection of glass negatives. After his death in Paris in September 1944, his heirs sold the collection to the Library of Congress. In the early 21st century the Library digitized the Prokudin-Gorsky Collection and made it freely available to the global public. A few Russian websites now have versions of the collection. In 1986 the architectural historian and photographer William Brumfield organized the first exhibit of Prokudin-Gorsky photographs at the Library of Congress. Over a period of work in Russia beginning in 1970, Brumfield has photographed most of the sites visited by Prokudin-Gorsky. This series of articles juxtaposes Prokudin-Gorsky’s views of architectural monuments with photographs taken by Brumfield decades later.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox